lingvo.wikisort.org - Language

The Cimmerians (Akkadian: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() , romanized: mat Gimirrāya;[1][2] Hebrew: גֹּמֶר, romanized: Gōmer;[3][4] Ancient Greek: Κιμμέριοι, romanized: Kimmerioi; Latin: Cimmerii[5]) were an ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic people originating in the Caspian steppe, part of whom subsequently migrated into West Asia. Although the Cimmerians were culturally Scythian, they formed an ethnic unit separate from the Scythians proper, to whom the Cimmerians were related and who displaced and replaced the Cimmerians.[6]

, romanized: mat Gimirrāya;[1][2] Hebrew: גֹּמֶר, romanized: Gōmer;[3][4] Ancient Greek: Κιμμέριοι, romanized: Kimmerioi; Latin: Cimmerii[5]) were an ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic people originating in the Caspian steppe, part of whom subsequently migrated into West Asia. Although the Cimmerians were culturally Scythian, they formed an ethnic unit separate from the Scythians proper, to whom the Cimmerians were related and who displaced and replaced the Cimmerians.[6]

Cimmerians | |

|---|---|

| unknown–c. 630s BC | |

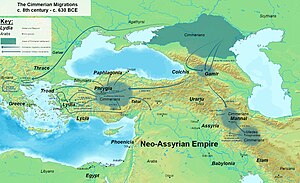

The Cimmerian migrations across West Asia | |

| Common languages | Scythian |

| Religion | Scythian religion (?) Ancient Iranian religion (?) Luwian religion (?) |

| Government | Monarchy |

| King | |

| Historical era | Iron Age Scythian cultures |

• Established | unknown |

• Disestablished | c. 630s BC |

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

The Cimmerians themselves left no written records, and most information about them is largely derived from Assyrian records of the 8th to 7th centuries BC and from Graeco-Roman authors from the 5th century BC and later.

Name

The English name Cimmerians is derived from Latin Cimmerii, itself derived from the Ancient Greek Kimmerioi (Κιμμεριοι), of an ultimately uncertain origin for which there have been various proposals:

- according to János Harmatta, it was derived from Old Iranian *Gayamira, meaning "union of clans."[7]

- Sergey Tokhtasyev and Igor Diakonoff derive it from an Old Iranian term *Gāmīra or *Gmīra, meaning "mobile unit."[5][8]

- Askold Ivantchik derives the name of the Cimmerians from an original form *Gimĕr- or *Gimĭr-, of uncertain meaning.[9]

Identification

The Cimmerians were a nomadic Iranian people of the Eurasian Steppe.[5][10][11][7][12] Archaeologically, there was no difference between the material cultures of the pre-Scythian populations living in the areas corresponding to the Caucasian steppe and the Volga and Don river regions around it, and there were also no other significant differences between the Cimmerians and the Scythians, who were related populations indistinguishable from each other in terms of culture and origins.[13][14]

Other suggestions for the ethnicity for the Cimmerians include the possibility of their being Thracian,[15] or Thracians with an Iranian ruling class, or a separate group closely related to Thracian peoples, as well as a Maeotian origin.[16] However, the proposal of a Thracian origin of the Cimmerians has been criticised as arising from a confusion by Strabo between the Cimmerians and their allies, the Thracian tribe of the Treri.[5][17]

Location

The original homeland of the Cimmerians before they migrated into West Asia was in the steppe situated to the north of the Caspian Sea and to the west of the Araxēs river until the Cimmerian Bosporus, and some Cimmerians might have nomadised in the Kuban steppe; the Cimmerians thus originally lived in the Caspian and Caucasian steppes, in the area corresponding to present-day Southern Russia.[17][13][18] The region of the Pontic Steppe until the Lake Maiōtis was instead inhabited by the Agathyrsi, who were another nomadic Iranian tribe related to the Cimmerians.[19] The later claim by Greek authors that the Cimmerians lived in the Pontic Steppe around the Tyras river was a retroactive invention dating from after the disappearance of the Cimmerians.[17]

During the initial phase of their presence in West Asia, the Cimmerians lived in a country which Mesopotamian sources called Gamir (![]()

![]()

![]() ), that is the Land of the Cimmerians, located around the Kuros river, to the north and north-west of Lake Sevan and the south of the Darial or Klukhor passes, in a region of Transcaucasia to the east of Colchis corresponding to the modern-day Gori, in southern Georgia.[17][20]

), that is the Land of the Cimmerians, located around the Kuros river, to the north and north-west of Lake Sevan and the south of the Darial or Klukhor passes, in a region of Transcaucasia to the east of Colchis corresponding to the modern-day Gori, in southern Georgia.[17][20]

The Cimmerians later split into two groups, with a western horde located in Anatolia, and an eastern horde which moved into Mannaea and later Media.[21]

History

Origins

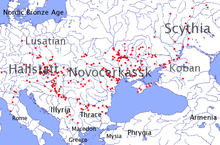

The Cimmerians were originally part of a larger group of Central Asian nomadic populations who migrated to the west and formed new tribal groupings in the Pontic and Caspian steppes, with their success at expanding into Eastern Europe happening thanks to the development of mounted nomadic pastoralism and the adoption of effective weapons suited to equestrian warfare by these nomads. The steppe cultures to which the Cimmerians belonged in turn influenced the cultures of Central Europe such as the Hallstatt culture, and the Cimmerians themselves lived in the steppe situated to the north of the Caspian Sea and to the west of the Araxēs river, while the region of the Pontic Steppe until the Lake Maiōtis was instead inhabited by the Agathyrsi, who were another nomadic Iranian tribe related to the Cimmerians.[17][19]

The Cimmerians are first mentioned in the 8th century BC in Homer's Odyssey as a people living beyond the Oceanus, in a land permanently deprived of sunlight at the edge of the world and close to the entrance of Hades; this mention is poetic and contains no reliable information about the real Cimmerians. Homer's story might however have used as its source the story of the Argonauts, which itself focused on the kingdom of Colchis, on whose eastern borders the Cimmerians were living in the 8th century BC.[17] This corresponds to the 6th century BC records of Aristeas of Proconnesus and the later writings of Herodotus of Halicarnassus, according to whom the Cimmerians lived in the steppe to the immediate north of the Caspian Sea, with the Araxēs river forming their eastern border which separated them from the Scythians,[17][19][5][22] although some tribes of the Scythians, a nomadic Iranian tribe living in Central Asia related to the Cimmerians, nomadised in the Caspian Steppe along the Cimmerians.[14] The Cimmerians thus never formed the mass of the population of the Pontic Steppe, and neither Aristeas nor Hesiod ever recorded them as living in this area.[13]

The social structure of the Cimmerians, according to Herodotus of Halicarnassus, comprised two groups of roughly equal numbers: the Cimmerians proper, or "commoners", and the "kings" or "royal race" – implying that the ruling classes and lower classes originally constituted two different peoples, who retained distinct identities as late as the end of the 2nd millennium BC. Hence the "kings" may have originated as an element of an Iranian-speaking people (such as the Scythians), who had imposed their rule on a section of the people of the Catacomb culture, who were the Cimmerian "commoners."[23]

In the 8th to 7th centuries BC, the Cimmerians were disturbed by a significant movement of the nomads of the Eurasian Steppe: this movement started when the bulk of the Scythians migrated westwards across the Araxēs river,[13] under the pressure of another related Central Asian nomadic Iranian tribe, either the Massagetae[24] or the Issedones,[17] following which the Scythians moved into the Caspian and Caucasian Steppes, assimilated most of the Cimmerians and conquered their territory, while the rest of the Cimmerians were displaced and forced to migrate to the south into West Asia.[14] This displacement of the Cimmerians by the Scythians is attested archaeologically in a disturbance of the Chernogorovka-Novocherkassk culture associated with the Cimmerians.[7][24][19]

Under Scythian pressure, the Cimmerians migrated to the south into West Asia.[5] The story recounted by Greek authors, according to which the Cimmerian aristocrats, unwilling to leave their lands, killed each other and were buried in a kurgan near the Tyras river, after which only the Cimmerian "commoners" migrated to West Asia, is contradicted by how powerful the Cimmerians were according to Assyrian sources contemporaneous with their presence in West Asia; this story was thus was either a Pontic Greek folk tale which originated after the disappearance of the Cimmerians[17] or a later Scythian legend reflecting the motif of vanished ancient lost peoples which is widespread in folk traditions.[25]

In West Asia

The Cimmerians who migrated into West Asia fled through the Klukhor, Alagir and Darial Gorge passes in the Greater Caucasus mountains,[26][17] that is through the western Caucasus and Georgia into Kolkhis, where the Cimmerians initially settled during the 720s BC.[27] During this period, Cimmerians lived in a country which Mesopotamian sources called Gamir, the Land of the Cimmerians, located around the Kuros river, to the north and north-west of Lake Sevan and the south of the Darial or Klukhor passes, in a region of Transcaucasia to the east of Kolkhis corresponding to the modern-day Gori, in southern Georgia.[17][20] Transcaucasia would remain the Cimmerians' centre of operations during the early phase of their presence in West Asia until the early 660s BC.[5]

The Scythians later also expanded to the south, appearing in West Asia forty years after the Cimmerians, although they followed the coast of the Caspian Sea and arrived in the region of present-day Azerbaijan.[28][29][17][3]

The inroads of the Cimmerians and the Scythians into West Asia over the course of the 8th to 6th centuries BC would destabilise the political balance which had prevailed in the region between the states of Assyria, Urartu, Mannaea and Elam on one side and the mountain and tribal peoples on the other.[13]

In Transcaucasia

The Cimmerians might have defeated attacks by the Urartian kings against Colchis and the nearby areas during the 720s BC.[17]

The first mention of the Cimmerians in the records of the Neo-Assyrian Empire was from between 720 and 714 BC, when Assyrian intelligence by the crown prince Sennacherib reported to the king Sargon II that the Cimmerians had attacked Urartu's province of Uasi through the territory of the kingdom of Mannaea. A counter-attack against the Cimmerians at Guriania in what is now Georgia by the Urartian king Rusa I,[5][30] during a campaign where Rusa I himself, his commander in chief, as well as thirteen governors united all the armed forces of the kingdom, was however heavily defeated by the Cimmerians, and the governor of the Urartian province of Uasi was killed. This defeat weakened Urartu significantly enough that Sargon II was able to successfully attack and defeat it, and Rusa I committed suicide in consequence.[20]

During the period corresponding to Sargon II's reign, a section of the Cimmerians moved into the area of the kingdom of Mannaea.[21]

The Cimmerians' presence in Anatolia might have started around 709 BC, and the king Midas II of Muški (Phrygia), who had previously been a bitter opponent of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in Anatolia, consequently ended hostilities with the Assyrians after and sent a delegation to Sargon II to attempt to form an alliance against the Cimmerians.[31][32][33]

In 705 BC, Sargon II died in battle, most likely during a campaign against the Anatolian kingdom of Tabal, or possibly during a battle in which the Cimmerians were participants in either the region of Tabal or in Nedia.[34][20][31][32]

After Sargon II's death, his son and successor Sennacherib secured the northwestern Assyrian borders,[32] and the Cimmerians ceased being mentioned in Assyrian records during Sennacherib's reign (from 705 to 681 BC); the Cimmerians would start being mentioned again by the Assyrians only under the reign of Sennacherib's own son and successor, Esarhaddon.[21] During this time, the Cimmerians were allied with the Scythians, and the two groups, in alliance with the Medes, who were an Iranian people of West Asia to whom the Scythians and Cimmerians were distantly related, were threatening the eastern frontier of Urartu during the reign of its king Argishti II.[18] Argishti II's successor, Rusa II, built several fortresses in the east of Urartu's territory, including that of Teishebaini, to monitor and repel attacks by the Cimmerians, the Mannaeans, the Medes, and the Scythians.[31]

During the period coinciding with the rule of the Assyrian king Esarhaddon (reigned 681–669 BC), the bulk of the Cimmerians migrated from Transcaucasia into Anatolia, while a smaller group remained in the area near the kingdom of Mannaea where they had been settled since the time of Sargon II, respectively forming a "western" and an "eastern" division of Cimmerians.[21]

In Iran

Between 680/679 and 678/677 BC,[35] the eastern group of Cimmerians allied with the Mannaeans and the Scythian king Išpakaia to attack Assyria, with the Scythians raiding far in the south till the Assyrian province of Zamua. These allied forces were defeated by Esarhaddon, who had become the king of the Neo-Assyrian empire.[36][13]

By 677 BC, the Cimmerians were present on the territory of Mannai,[5] and in 676 BC they were its allies against an Assyrian attack, after which the eastern Cimmerians remained allied to Mannai against Assyria.[21] In the western Iranian plateau, these eastern Cimmerians might have introduced Bronze articles from the Koban culture into the Luristan bronze culture.[37] The Mannaeans, in alliance with the eastern Cimmerians and the Scythians (the latter of whom attacked the borderlands of Assyria from across the territory of the kingdom of Ḫubuškia), were able to expand their territories at the expense of Assyria and capture the fortresses of Šarru-iqbi and Dūr-Ellil. Negotiations between the Assyrians and the Cimmerians appeared to have followed, according to which the Cimmerians promised not to interfere in the relations between Assyria and Mannai, although a Babylonian diviner in Assyrian service warned Esarhaddon not to trust either the Mannaeans or the Cimmerians and advised him to spy on both of them.[13]

The eastern Cimmerian group later moved to the south, into Media, with the Scythians as their northern neighbours and occasional allies, and in the mid 670s BC, these eastern Cimmerians were recorded by the Assyrians as a possible threat against the collection of tribute from Media. Around the same time, in alliance with the Scythians, the eastern Cimmerians were menacing the Assyrian provinces of Parsumaš and Bīt Ḫamban, and these joint Cimmerian-Scythian forces together were threatening communication between the Assyrian Empire and its vassal of Ḫubuškia.[21][36] In 676 BC, Esarhaddon responded by carrying out a military campaign against Mannai during which he killed Išpakaia.[13]

By the late 670s BC, the Scythians had become the allies of the Assyrians after Išpakaia's successor, Bartatua, had married a daughter of Esarhaddon, while the eastern Cimmerians remained hostile to Assyria and were allied to Ellipi and the Medes. When Ellipi and the Medes successfully rebelled against Assyria under Kashtariti from 671 to 669 BC, the eastern Cimmerians were allied to them.[21][31]

In Anatolia

By the later 7th century BC, the centre of operations of the larger, western, division of the Cimmerians was located in Anatolia.[5][21]

In 679 BC the Cimmerian king Teušpa was defeated and killed by Esarhaddon near Ḫubušna in Cappadocia.[31][32][5][21][38] Despite this victory, the military operations of the Assyrians were not fully successful and they were not able to firmly occupy the areas around Ḫubušna, nor were they able to secure their borders, and the Assyrian province of Quwê was left vulnerable to invasions from Tabal, Kuzzurak and Ḫilakku;[21] the Cimmerians had thus ended all Assyrian control in Anatolia.[39]

An Assyrian contract dating to the same as Esarhaddon's victory over Teušpa records of the existence of a "Cimmerian detachment" in Nineveh, although it is uncertain whether this refers to Cimmerian mercenaries in Assyrian service, or simply of Assyrian soldiers armed in the "Cimmerian-style", that is using Cimmerian bows and horse harnesses.[21]

Around 675 BC, the Cimmerians, under their king Tugdammi (the Lugdamis of the Greek authors), in alliance with the Urartian king Rusa II carried out a military campaign to the west, against Muški (Phrygia), Ḫate (the Neo-Hittite state of Melid), and Ḫaliṭu (either the Alizōnes or the Khaldoi);[31] this campaign resulted in the invasion and destruction of Phrygia, whose king Midas II committed suicide.[34][31][30][32][21][17] The Cimmerians plundered the Phrygian capital of Gordion, but they neither settled there nor destroyed its fortifications,[40] although they appear to have consequently partially subdued the Phrygians, and an Assyrian oracular text from the later 670s BC mentioned the Cimmerians and the Phrygians, who had possibly been subdued by the Cimmerians, as allies against the Assyrians' newly conquered province of Melid.[5][21]

A document from 673 BC records Rusa II as having recruited a large number of Cimmerian mercenaries, and Cimmerian allies of Rusa II probably participated in a military expedition of his in 672 BC.[34] From 671 to 669 BC, Cimmerians in service of Rusa II attacked the Assyrian province of Šubria near the Urartian border.[37][21]

Between 671 and 670 BC, some Cimmerian divisions were recorded as serving in the Assyrian army, although these divisions might have instead simply referred to the "Cimmerian style" armed Assyrian soldiers.[5]

At yet unknown dates, the Cimmerians imposed their rule on Cappadocia, invaded Bithynia, Paphlagonia and the Troad,[34] and took the recently founded Greek colony of Sinope, whose initial settlement was destroyed and whose first founder Habrōn was killed in the invasion, and which was later re-founded by the Greek colonists Kōos and Krētinēs.[41] Along with Sinope, the Greek colony of Cyzicus was also destroyed during these invasions and had to be later re-founded.[42] In the beginning of that decade, the Cimmerians attacked the kingdom of Lydia,[34] which had been filling the power vacuum in Anatolia created by the destruction of Phrygia by establishing itself as a new rising regional power.[31] The Lydian king Gyges, attempting to find help to face the Cimmerian invasions, contacted Esarhaddon's successor who had succeeded him as king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, Ashurbanipal, beginning in 667 BC, and his struggle against Cimmerians soon turned in his favour.[39][43][40] Gyges soon defeated the Cimmerians in 665 BC without Assyrian help, and he sent Cimmerian soldiers captured while attacking the Lydian countryside as gifts to Ashurbanipal.[44][5] According to the Assyrian records describing these events, the Cimmerians already had formed sedentary settlements in Anatolia.[43]

Assyrian records in 657 BC of a "bad omen" for the "Westland"[40] might have referred to either another Cimmerian attack on Lydia,[44][39] or a conquest by Tugdammi of the western possessions of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, possibly Quwê or somewhere in Syria,[45] following their defeat by Gyges.[43] These Cimmerian aggressions worried Ashurbanipal about the security of the north-west border of the Neo-Assyrian Empire enough that he sought answers concerning this situation through divination,[5] and as a result of these Cimmerian conquests, by 657 BC the Assyrian divinatory records were calling the Cimmerian king by the title of šar-kiššati ("King of the Universe"), a title which in the Mesopotamian worldview could belong to only a single ruler in the world at any given time and was normally held by the King of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. These divinatory texts also assured to Ashurbanipal that he would eventually regain the kiššūtu, that is the world hegemony, captured by the Cimmerians: the kiššūtu, which was considered to rightfully belong to the Assyrian king, had been usurped by the Cimmerians and had to be won back by Assyria. Thus, the Cimmerians had become a force feared by Ashurbanipal, and Tugdammi's successes against Assyria meant that he had become recognised in the ancient Near East as equally powerful as Ashurbanipal. This situation remained unchanged throughout the rest of the 650s BC and the early 640s BC.[43]

As the result of these Assyrian setbacks, Gyges could not rely on Assyrian support against the Cimmerians and he ended diplomacy with the Neo-Assyrian Empire,[43] and Ashurbanipal responded to Gyges's disengagement from Assyria by cursing him.[40][46]

The Cimmerians attacked Lydia for a third time in 644 BC: this time, they defeated the Lydians and captured their capital, Sardis, and Gyges died during this attack.[44][39][5][34][30][40] Gyges was succeeded by his son Ardys, who resumed diplomatic activity with Assyria;[47][44] Ashurbanipal, whose Anatolian borders were still in a delicate situation due to the Cimmerians, was himself willing to form alliances with any state in Anatolia which was capable of successfully fighting the Cimmerians.[39][40]

After sacking Sardis, Lygdamis led the Cimmerians into invading the Greek city-states of Ionia and Aeolis on the western coast of Anatolia, which caused the inhabitants of the Batinētis region to flee to the islands of the Aegean Sea, and later Greek writings by Callimachus and Hesychius of Alexandria preserve the record that Lygdamis had destroyed the Artemision of Ephesus.[43] Among the other Greek cities destroyed during these invasions was Magnesia on the Meander.[42]

After this third invasion of Lydia and the attack on the Asiatic Greek cities, around 640 BC the Cimmerians moved to Cilicia on the north-west border of the Assyrian empire, where Tugdammi allied with Mugallu, the king of Tabal, against Assyria, during which period the Assyrian records called him a "mountain king and an arrogant Gutian (that is a barbarian) who does not know how to fear the gods." However, after facing a revolt against himself, Tugdamme allied with Assyria and acknowledged Assyrian overlordship, and sent tribute to Ashurbanipal, to whom he swore an oath. Tugdammi soon broke this oath and attacked the Assyrian Empire again, but he fell ill and died in 640 BC, and was succeeded by his son Sandakšatru, who attempted to continue Tugdammi's attacks against Assyria but failed just like his father.[44][5][39][43][48][49][50]

By the later part of the 7th century BC, the Cimmerians were nomadising in West Asia together with the Thracian Treri tribe who had migrated across the Thracian Bosporus and invaded Anatolia.[13][17] In 637 BC, Sandakšatru's Cimmerians participated in another attack on Lydia, this time led by the Treres under their king Kōbos, and in alliance with the Lycians.[44] During this invasion, in the seventh year of the reign of Gyges's son Ardys, the Lydians were defeated again and for a second time Sardis was captured, except for its citadel, and Ardys might have been killed in this attack.[51] Ardys's son and successor, Sadyattes, might possibly also have been killed in another Cimmerian attack on Lydia in c. 635 BC.[51][40]

The power of the Cimmerians had eventually dwindled quickly after Tugdammi's death, and soon these Cimmerian attacks on Lydia, with Assyrian approval[52] and in alliance with the Lydians,[53] the Scythians under their king Madyes entered Anatolia, expelled the Treres from Asia Minor, and defeated the Cimmerians so that they no longer constituted a threat again, following which the Scythians extended their domination to Central Anatolia[3] until they were themselves expelled by the Medes from West Asia in the 600s BC.[44][5] This final defeat of the Cimmerians was carried out by the joint forces of Madyes, who Strabo credits with expelling the Cimmerians from Asia Minor, and of Gyges's great-grandson, the king Alyattes of Lydia, whom Herodotus of Halicarnassus and Polyaenus claim finally defeated the Cimmerians.[43][17]

Following this final defeat,[5] the Cimmerians likely remained in the region of Cappadocia, whose name in Armenian, Գամիրք Gamirkʿ, may have been derived from the name of the Cimmerians.[34] A group of Cimmerians might also have subsisted for some time in the Troas, around Antandrus,[34] until they were finally defeated by Alyattes of Lydia.[54] The remnants of the Cimmerians were eventually assimilated by the populations of Anatolia,[17] and they completely disappeared from history after their defeat by Madyes and Alyattes.[5]

In Europe

It has been hypothesised that some Cimmerians might have migrated into Eastern, South-east and Central Europe, although such identification is presently considered very uncertain.[17]

Impact

The inroads of the Cimmerians and the Scythians into West Asia over the course of the 8th to 6th centuries BC had destabilised the political balance which had prevailed in the region between the states of Assyria, Urartu, Mannaea and Elam on one side and the mountain and tribal peoples on the other, resulting in the destruction of these former kingdoms and their replacement by new powers, including the kingdoms of the Medes and of the Lydians.[13]

Legacy

After the end of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, the scribes of the Neo-Babylonian Empire which replaced it used the term Gimirri indiscriminately to refer to all the nomads of the steppes, including both the Pontic Scythians and the Central Asian Saka.[6] The Persian Achaemenids who conquered the Neo-Babylonian Empire continued this tradition of using the name of the Cimmerians to refer to all steppe nomads in the Akkadian language, as attested in the Behistun inscription.[25] The Byzantines from a millennium and onwards later similarly referred to the Huns, Slavs, and other populations as "Scythians."[25]

Homer's mention of the Cimmerians as living deprived from sunlight and close to the entrance of Hades influenced later Graeco-Roman authors who, writing centuries after the disappearance of the historical Cimmerians, conceptualised of this people as the one described by Homer, and therefore assigned to them various fantastical locations and histories:[17][55]

- Ephorus of Cyme in the 4th century BC placed the Cimmerians near the city of Cumae in Magna Graecia, where there was located a Ploutonion and an oracle of the dead, as well as the Lake Avernus, which possessed strange properties. According to Ephorus's narrative, these Cimmerians lived underground and would go out only at night because of a tradition of theirs to never see the Sun.

- Hecataeus of Abdera placed the "Cimmerian city" in Hyperborea

- Posidonius of Apamea wrote that the Cimmerians who passed into West Asia were merely a small body of exiles, while the bulk of the Cimmerians lived in the thickly wooded and sun-less far north, between the shores of the Oceanus and the Hercynian Forest, and were the same people known as the Cimbri. Both the Cimmerians and the Cimbri were perceived by the Greeks as fierce barbarian tribes who had caused significant destruction for the peoples they had invaded, and since their names were similar, the Greek traditions progressively equated and then identified them with each other.

- This assertion was criticised by Plutarch as being conjectural rather than based on concrete historical evidence.

- Strabo and Diodorus of Sicily, using Posidonius as their sources, also equated the Cimmerians and the Cimbri.

The Cimmerians appear in the Hebrew Bible under the name of Gōmer (גֹּמֶר), where Gōmer is closely linked to ʾAškənāz (אשכנז), that is to the Scythians.[13][3][4]

In sources beginning with the Royal Frankish Annals, the Merovingian kings of the Franks traditionally traced their lineage through a pre-Frankish tribe called the Sicambri (or Sugambri), mythologized as a group of "Cimmerians" from the mouth of the Danube river. The historical Sicambri, however, were a Germanic tribe from Gelderland in modern Netherlands and are named for the Sieg river.[56]

Early modern historians asserted Cimmerian descent for the Celts or the Germans, arguing from the similarity of Cimmerii to Cimbri or Cymry, noted by 17th-century Celticists. But the word Cymro "Welshman" (plural: Cymry) is now accepted by Celtic linguists as being derived from a Brythonic word *kom-brogos, meaning "compatriot".[57][58][59][60]

According to Georgian national historiography, the Cimmerians, in Georgian known as Gimirri, played an influential role in the development of the Colchian and Iberian cultures.[61] The modern Georgian word for "hero", გმირი gmiri, is said to derive from their name.[citation needed]

It has also been speculated that the modern Armenian city of Gyumri (Arm. Գյումրի [ˈgjumɾi]), founded as Kumayri (Arm. Կումայրի), derived its name from the Cimmerians who conquered the region and founded a settlement there.[62]

In popular culture

The character of Conan the Barbarian, created by Robert E. Howard in a series of fantasy stories published in Weird Tales from 1932, is canonically a Cimmerian: in Howard's fictional Hyborian Age, the Cimmerians are a pre-Celtic people who were the ancestors of the Irish and Scots (Gaels).

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, a novel by Michael Chabon, includes a chapter describing the (fictional) oldest book in the world, "The Book of Lo", created by ancient Cimmerians.

Manau's song "La Tribu de Dana" recounts an imaginary battle between Celts and enemies identified by the narrator as Cimmerians.

Archaeology

Archaeologically, the Cimmerians are associated with the Chernogorovka-Novocherkassk Culture of the west Eurasian steppe, which itself showed strong influences originating from the east in Central Asia and Siberia (more specifically from the Karasuk. Arzhan, and Altai cultures), as well as from the Kuban culture of the Caucasus which contributed to its development,[19] although an alternative view is that the Cimmerians instead belonged, materially, to the Early Scythian culture.[41]

Cimmerian remains from the period of their presence in Anatolia include a burial from the village of İmirler in the Amasya Province of Turkey which contains typically Early Scythian weapons and horse harnesses. Another Cimmerian burial, located at about 100 km to the east of İmirler and 50 km from Samsun, contained 250 Scythian-type arrowheads.[41]

Language

| Cimmerian | |

|---|---|

| Region | North Caucasus |

| Era | unknown-7th century BC |

Language family | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis) |

Linguist List | 08i |

| Glottolog | None |

According to the historian Muhammad Dandamayev and the linguist János Harmatta, the Cimmerians spoke a dialect belonging to the Scythian group of Iranian languages, and were able to communicate with Scythians proper without needing interpreters.[63][7] The Iranologist Ľubomír Novák considers Cimmerian to be a relative of Scythian which exhibited similar features as Scythian, such as the evolution of the sound /d/ into /l/.[64]

The recorded personal names of the Cimmerians were either Iranian, reflecting their origins, or Anatolian, reflecting the cultural influence of the native populations of Asia Minor on them after their migration there.[13]

Only a few personal names in the Cimmerian language have survived in Assyrian inscriptions:

- Teušpa:

- According to the linguist János Harmatta, it goes back to Old Iranian *Tavispaya, meaning "swelling with strength",[7] although Askold Ivantchik has criticised this proposal on phonetic grounds.[21]

- Askold Ivantchik instead posits three alternative suggestions for an Old Iranian origin of Teušpa:[21]

- *Taiu-aspa "abductor of horses"

- *Taiu-spā "abductor dog"

- *Daiva-spā "divine dog"

- Tugdammē or Dugdammē (

), and recorded as Lugdamis (Λυγδαμις) and Dugdamis (Δυγδαμις) by Greek authors

), and recorded as Lugdamis (Λυγδαμις) and Dugdamis (Δυγδαμις) by Greek authors

- According to János Harmatta, it goes back to Old Iranian *Duydamaya "giving happiness."[7]

- Edwin M. Yamauchi also interprets the name as Iranian, citing Ossetic Тух-домӕг (Tux-domæg), meaning "ruling with strength,"[65] although this proposal has been criticised because Тух-домӕг represents the modern phonetics of Ossetian and its form during the Old Iranian period when the Cimmerians lived would have been *Tavaʰ-dam-ak.[43]

- Askold Ivantchik instead suggests that the name Dugdammê/Lugdamis was a loanword from an Anatolian language, more specifically Luwian, while also accepting the alternative possibility of a derivation from a variant of the name of the Hurrian deity Teyśəba/Tešub.[43]

- Ľubomír Novák has noted that the attestation of this name in the forms Dugdammê and Tugdammê in Akkadian and the forms Lugdamis and Dugdamis in Greek shows that its first consonant had experienced the change of the sound /d/ to /l/, which is consistent with the phonetic changes attested in the Scythian languages.[64]

- Sandakšatru: this is an Iranian reading of the name, and Manfred Mayrhofer (1981) points out that the name may also be read as Sandakurru.

Isaac Asimov attempted to trace various place names to Cimmerian origins. He suggested that Cimmerium gave rise to the Turkic toponym Qırım (which in turn gave rise to the name "Crimea").[66]

Genetics

A genetic study published in Science Advances in October 2018 examined the remains of three Cimmerians buried between around 1000 and 800 BC. The two samples of Y-DNA extracted belonged to haplogroups R1b1a and Q1a1, while the three samples of mtDNA extracted belonged to haplogroups H9a, C5c and R. [67]

Another genetic study published in Current Biology in July 2019 examined the remains of three Cimmerians. The two samples of Y-DNA extracted belonged to haplogroups R1a-Z645 and R1a2c-B111, while the three samples of mtDNA extracted belonged to haplogroups H35, U5a1b1 and U2e2.[68]

Cimmerian kings

Kings of the western (Anatolian) Cimmerians

- Teušpa (?-679 BC)

- Tugdamme (679-640 BC)

- Sandakšatru (640-c. 630s BC)

See also

- Agathyrsi

- Scythians

- Scythian cultures

- Umman Manda

- Medes

- Cimbri

References

Citations

- Parpola, Simo (1970). Neo-Assyrian Toponyms. Kevelaer, Germany: Butzon & Bercker. pp. 132–134.

- "Gimirayu [CIMMERIAN] (EN)". Open Richly Annotated Cuneiform Corpus. University of Pennsylvania.

- Phillips, E. D. (1972). "The Scythian Domination in Western Asia: Its Record in History, Scripture and Archaeology". World Archaeology. 4 (2): 129–138. doi:10.1080/00438243.1972.9979527. JSTOR 123971. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- Barnett, R. D. (1975). "Phrygia and the Peoples of Anatolia in the Iron Age". In Edwards, I. E. S.; Gadd, C. J.; Hammond, N. G. L.; Sollberger, E. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 2. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 417–442. ISBN 978-0-521-08691-2.

- Tokhtas’ev 1991.

- Tokhtas’ev 1991: "As the Cimmerians cannot be differentiated archeologically from the Scythians, it is possible to speculate about their Iranian origins. In the Neo-Babylonian texts (according to D’yakonov, including at least some of the Assyrian texts in Babylonian dialect) Gimirri and similar forms designate the Scythians and Central Asian Saka, reflecting the perception among inhabitants of Mesopotamia that Cimmerians and Scythians represented a single cultural and economic group"

- Harmatta, János (1996). "10.4.1. The Scythians". In Hermann, Joachim; de Laet, Sigfried (eds.). History of Humanity. Vol. 3. UNESCO. p. 181. ISBN 978-9-231-02812-0.

- Diakonoff 1985.

- Ivantchik 1993, p. 127-154.

- von Bredow, Iris (2006). "Cimmeriin". Brill's New Pauly, Antiquity volumes. doi:10.1163/1574-9347_bnp_e613800.

(Κιμμέριοι; Kimmérioi, Lat. Cimmerii). Nomadic tribe probably of Iranian descent, attested for the 8th/7th cents. BCE.

- Liverani, Mario (2014). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. Routledge. p. 604. ISBN 978-0415679060.

Cimmerians (Iranian population)

- Kohl, Philip L.; Dadson, D.J., eds. (1989). The Culture and Social Institutions of Ancient Iran, by Muhammad A. Dandamaev and Vladimir G. Lukonin. Cambridge University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0521611916.

Ethnically and linguistically, the Scythians and Cimmerians were kindred groups (both people spoke Old Iranian dialects) (...)

- Diakonoff 1985, p. 89-109.

- Melyukova 1990, pp. 97–110.

- Frye, Richard Nelson (1984). The History of Ancient Iran. Verlag C.H. Beck. p. 70. ISBN 978-3406093975.

The Cimmerians lived north of the Caucasus mountains in South Russia and probably were related to the Thracians, but they surely were a mixed group by the time they appeared south of the mountains, and we hear of them first in the year 714 B.C. after they presumably had defeated the Urartians

- Sulimirski & Taylor 1991, p. 555.

- Olbrycht, Marek Jan (2000). "The Cimmerian Problem Re-Examined: the Evidence of the Classical Sources". In Pstrusińska, Jadwiga; Fear, Andrew (eds.). Collectanea Celto-Asiatica Cracoviensia. Kraków, Poland: Księgarnia Akademicka. ISBN 978-8-371-88337-8.

- Barnett 1982, pp. 333–356.

- Olbrycht, Marek Jan (2000). "Remarks on the Presence of Iranian Peoples in Europe and Their Asiatic Relations". In Pstrusińska, Jadwiga; Fear, Andrew (eds.). Collectanea Celto-Asiatica Cracoviensia. Kraków, Poland: Księgarnia Akademicka. pp. 101–140. ISBN 978-8-371-88337-8.

- Ivantchik 1993, p. 19-55.

- Ivantchik 1993, p. 57-94.

- Rolle, Renato (1977). "Urartu und die Reiternomaden" [Urartu and the Mounted Nomads]. Saeculum (in German). 28 (3): 291–339. doi:10.7788/saeculum.1977.28.3.291. S2CID 170768431. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- Sulimirski & Taylor 1991, p. 556.

- Sulimirski & Taylor 1991, p. 553.

- Ivantchik, Askold (2001). "The Current State of the Cimmerian Problem". Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia. 7 (3): 307–339. doi:10.1163/15700570152758043. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- Diakonoff 1985, p. 93.

- Barnett 1982, p. 355.

- Diakonoff 1985, p. 97.

- Sulimirski & Taylor 1991, p. 562.

- Cook 1982.

- Barnett 1982, pp. 356–365.

- Hawkins 1982.

- Grayson, A. K. (1991). "Assyria: Tiglath-pileser III to Sargon II (744-705 B.C.)". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S.; Hammond, N. G. L.; Sollberger, E.; Walker, C. B. F. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 71–102. ISBN 978-1-139-05429-4.

- Sulimirski & Taylor 1991, p. 559.

- Ivantchik 2018.

- Sulimirski & Taylor 1991, p. 564.

- Sulimirski & Taylor 1991, p. 560.

- Grayson, A. K. (1991). "Assyria: Sennacherib to Esarhaddon (704-669 B.C.)". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S.; Hammond, N. G. L.; Sollberger, E.; Walker, C. B. F. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 103–141. ISBN 978-1-139-05429-4.

- Grayson, A. K. (1991). "Assyria 668-635 B.C.: the reign of Ashurbanipal". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S.; Hammond, N. G. L.; Sollberger, E.; Walker, C. B. F. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 142-. ISBN 978-1-139-05429-4.

- Mellink 1991.

- Ivantchik, Askold (2010). "Sinope et les Cimmériens" [Sinope and the Cimmerians]. Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia (in French). 16: 65–72. doi:10.1163/157005711X560318. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- Graham 1982.

- Ivantchik 1993, p. 95-125.

- Spalinger, Anthony J. (1978). "The Date of the Death of Gyges and Its Historical Implications". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 98 (4): 400–409. doi:10.2307/599752. JSTOR 599752. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- Brinkman, J. A. (1991). "Babylonia in the Shadow of Assyria". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S.; Hammond, N. G. L.; Sollberger, E.; Walker, C. B. F. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–70. ISBN 978-1-139-05429-4.

- Braun, T. F. R. G. (1982). "The Greeks in Egypt". In Boardman, John; Hammond, N. G. L. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 32–56. ISBN 978-0-521-23447-4.

- Spalinger, Anthony (1976). "Psammetichus, King of Egypt: I". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 13: 133–147. doi:10.2307/40001126. JSTOR 40001126. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- Tuplin, Christopher (2004). "Medes in Media, Mesopotamia, and Anatolia: Empire, Hegemony, Domination or Illusion?". Ancient West & East. 3 (2): 223–251. doi:10.1163/9789047405870_002. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- Tuplin, Christopher (2013). "INTOLERABLE CLOTHES & A TERRIFYING NAME: THE CHARACTERISTICS OF AN ACHAEMENID INVASION FORCE". Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies. 124: 223–239.

- Novotny, Jamie; Jeffers, Joshua (2018). The Royal Inscriptions of Ashurbanipal (668–631 BC), Aššur-etel-ilāni (630–627 BC), and Sînšarraiškun (626–612 BC), Kings of Assyria. Vol. 1. University Park, United States: Eisenbrauns. p. 309. ISBN 978-1-575-06997-5.

- Dale, Alexander (2015). "WALWET and KUKALIM: Lydian coin legends, dynastic succession, and the chronology of Mermnad kings". Kadmos. 54: 151–166. doi:10.1515/kadmos-2015-0008. S2CID 165043567. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- Grousset, René (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 9. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

A Scythian army, acting in conformity with Assyrian policy, entered Pontis to crush the last of the Cimmerians

- Diakonoff 1985, p. 126.

- Leloux, Kevin (2018). La Lydie d'Alyatte et Crésus: Un royaume à la croisée des cités grecques et des monarchies orientales. Recherches sur son organisation interne et sa politique extérieure (PDF) (PhD). Vol. 1. University of Liège. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- Xydopoulos, Ioannis K. (2015). "The Cimmerians: their origins, movements and their difficulties". In Tsetskhladze, Gocha R.; Avram, Alexandru; Hargrave, James (eds.). The Danubian Lands Between the Black, Aegean and Adriatic Seas (7th Century BC-10th Century AD): Proceedings of the Fifth International Congress on Black Sea Antiquities (Belgrade - 17-21 September 2013). Archaeopress Publishing Limited. pp. 119–123. ISBN 978-1-784-91192-8.

- Geary, Patrick J. Before France and Germany: The Creation and Transformation of the Merovingian World. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988

- Geiriadur Prifysgol Cymru, vol. I, p. 770.

- Jones, J. Morris. Welsh Grammar: Historical and Comparative. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995.

- Russell, Paul. Introduction to the Celtic Languages. London: Longman, 1995.

- Delamarre, Xavier. Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise. Paris: Errance, 2001.

- Berdzenishvili, N., Dondua V., Dumbadze, M., Melikishvili G., Meskhia, Sh., Ratiani, P., History of Georgia, Vol. 1, Tbilisi, 1958, pp. 34–36

- "Cimmerian". Kumayri infosite. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- Dandamayev, Muhammad (27 January 2015). "MESOPOTAMIA i. Iranians in Ancient Mesopotamia". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

It seems that Cimmerians and Scythians (Sakai) were related, spoke among themselves different Iranian dialects, and could understand each other without interpreters.

- Novák, Ľubomír (2013). Problem of Archaism and Innovation in the Eastern Iranian Languages. Charles University. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- Yamauchi, Edwin M (1982). Foes from the Northern Frontier: Invading Hordes from the Russian Steppes. Grand Rapids MI USA: Baker Book House.

- Asimov, Isaac (1991). Asimov's Chronology of the World. New York City, United States: HarperCollins. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-062-70036-0.

- Krzewińska et al. 2018, Supplementary Materials, Table S3 Summary, Rows 23-25.

- Järve et al. 2019, Table S2.

Sources

- Barnett, R. D. (1982). "Urartu". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S.; Hammond, N. G. L.; Sollberger, E. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 3. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 314–371. ISBN 978-1-139-05428-7.

- Cook, J. M. (1982). "The Eastern Greeks". In Boardman, John; Hammond, N. G. L. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 196–221. ISBN 978-0-521-23447-4.

- Diakonoff, I. M. (1985). "Media". In Gershevitch, Ilya (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 2. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 36-148. ISBN 978-0-521-20091-2.

- Graham, A. J. (1982). "The colonial expansion of Greece". In Boardman, John; Hammond, N. G. L. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 83–162. ISBN 978-0-521-23447-4.

- Hawkins, J. D. (1982). "The Neo-Hittite States in Syria and Anatolia". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S.; Hammond, N. G. L.; Sollberger, E. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 372–441. ISBN 978-1-139-05428-7.

- Ivantchik, Askold (1993). Les Cimmériens au Proche-Orient [The Cimmerians in the Near East] (PDF) (in French). Fribourg, Switzerland; Göttingen, Germany: Editions Universitaires Fribourg (Switzerland); Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht (Germany). ISBN 978-3-727-80876-0.

- Ivantchik, Askold (2018). "Scythians". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Ivantchik, Askold (2000). Киммерийцы и скифы: Культурно-исторические и хронологические проблемы археологии восточноевропейских степей и Кавказа пред- и раннескифского времени [Cimmerians and Scythians: Cultural, Historical and Chronological Problems of the Archeology of the Eastern European Steppes and the Caucasus in the Pre- and Early Scythian Periods]. Moscow, Russia: Paleograph Press. ISBN 978-5-895-26009-8.

- Järve, Mari; et al. (July 11, 2019). "Shifts in the Genetic Landscape of the Western Eurasian Steppe Associated with the Beginning and End of the Scythian Dominance". Current Biology. Cell Press. 29 (14): 2430–2441. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.06.019. PMID 31303491.

- Krzewińska, Maja; et al. (October 3, 2018). "Ancient genomes suggest the eastern Pontic-Caspian steppe as the source of western Iron Age nomads". Science Advances. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 4 (10): eaat4457. Bibcode:2018SciA....4.4457K. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aat4457. PMC 6223350. PMID 30417088.

- Mellink, M. (1991). "The Native Kingdoms of Anatolia". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S.; Hammond, N. G. L.; Sollberger, E.; Walker, C. B. F. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 619–665. ISBN 978-1-139-05429-4.

- Melyukova, A. I. (1990). Sinor, Denis (ed.). The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 97–117. ISBN 978-0-521-24304-9.

- Sulimirski, Tadeusz; Taylor, T. F. (1991). "The Scythians". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S.; Hammond, N. G. L.; Sollberger, E.; Walker, C. B. F. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 547–590. ISBN 978-1-139-05429-4.

- Terenozhkin A.I., Cimmerians, Kiev, 1983

- Tokhtas’ev, Sergei R. (1991). "CIMMERIANS". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- Collection of Slavonic and Foreign Language Manuscripts – St.St Cyril and Methodius – Bulgarian National Library: http://www.nationallibrary.bg/slavezryk_en.html Archived 2009-06-27 at the Wayback Machine

Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии