lingvo.wikisort.org - Language

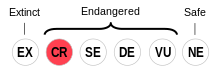

Nuxalk /ˈnuːhɒlk/, also known as Bella Coola /ˈbɛlə.ˈkuːlə/, is a Salishan language spoken by the Nuxalk people. Today, it is an endangered language with only 3 fluent speakers in the vicinity of the Canadian town of Bella Coola, British Columbia.[3][4] While the language is still sometimes called Bella Coola by linguists, the native name Nuxalk is preferred by some, notably by the Nuxalk Nation's government.[5][1]

| Nuxalk | |

|---|---|

| Bella Coola | |

| ItNuxalkmc[1] | |

| Native to | Canada |

| Region | Bella Coola area, Central Coast region, British Columbia |

| Ethnicity | 1,660 Nuxalk (2014, FPCC)[2] |

Native speakers | 17 (2014, FPCC)[2] |

Language family | Salishan

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | blc |

| Glottolog | bell1243 |

| ELP | Nuxalk |

Bella Coola is classified as Critically Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

Though the number of truly fluent speakers has not increased, the language is now taught in both the provincial school system and the Nuxalk Nation's own school, Acwsalcta, which means "a place of learning". Nuxalk language classes, if taken to at least the Grade 11 level, are considered adequate second-language qualifications for entry to the major B.C. universities. CKNN-FM Nuxalk Radio is also working to promote the language.

Name

The name "Nuxalk" for the language comes from the native nuxalk (or nuχalk), referring to the "Bella Coola Valley".[6] "Bella Coola" is a rendering of the Heiltsuk bḷ́xʷlá, meaning "stranger".[7]

Geographical distribution

Nowadays, Nuxalk is spoken only in Bella Coola, British Columbia, surrounded by Wakashan- and Athabascan-speaking tribes. It was once spoken in over 100 settlements, with varying dialects, but in the present day most of these settlements have been abandoned and dialectal differences have largely disappeared.[7]

Classification

Nuxalk forms its own subgroup of the Salish language family. Its lexicon is equidistant from Coast and Interior Salish, but it shares phonological and morphological features with Coast Salish (for example, the absence of pharyngeals and the presence of marked gender). Nuxalk also borrows many words from contiguous North Wakashan languages (especially Heiltsuk), as well as some from neighbouring Athabascan languages and Tsimshian.[7]

Phonology

Consonants

Nuxalk has 29 consonants depicted below in IPA and the Americanist orthography of Davis & Saunders when it differs from the IPA.

| Labial | Alveolar | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | sibilant | lateral | palatal | labialized | plain | labialized | ||||

| Stop | aspirated | pʰ ⟨p⟩ | tʰ ⟨t⟩ | t͡sʰ ⟨c⟩ | t͡ɬʰ ⟨ƛ⟩ | cʰ ⟨k⟩ | kʷʰ ⟨kʷ⟩ | qʰ ⟨q⟩ | qʷʰ ⟨qʷ⟩ | |

| ejective | pʼ ⟨p̓⟩ | tʼ ⟨t̓⟩ | t͡sʼ ⟨c̓⟩ | t͡ɬʼ ⟨ƛ̓⟩ | cʼ ⟨k̓⟩ | kʷʼ ⟨k̓ʷ⟩ | qʼ ⟨q̓⟩ | qʷʼ ⟨q̓ʷ⟩ | ʔ | |

| Fricative | s | ɬ ⟨ł⟩ | ç ⟨x⟩ | xʷ | χ ⟨x̣⟩ | χʷ ⟨x̣ʷ⟩ | (h) | |||

| Sonorant | m | n | l | j ⟨y⟩ | w | |||||

What are transcribed in the orthography as 'plain' velar consonants are actually palatals, and the sibilants s c c̓ palatalize to š č č̓ before x k k̓.

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | ||

| Mid | o | ||

| Open | a |

Allophony

/i/ may be pronounced:

- [ɪ] before postvelars

- [ɪː, ɛː] between postvelars

- [e̞, e̞ː], before a sonorant followed by a consonant or word boundary

- [i] adjacent to palatovelars

- [e] elsewhere

/a/ may be pronounced:

- [ɑ] ([ɒ]?) surrounded by postvelars

- [ɐ] before rounded velars followed by a consonant or word boundary

- [a] ([ä]?) before a sonorant followed by a consonant or word boundary

- [æ] elsewhere

/o/ may be pronounced:

- [o̞] surrounded by postvelars

- [o̞, o̞ː, ɔ, ɔː] before a sonorant followed by a consonant or word boundary

- [u, ʊ] before rounded velars followed by a consonant or word boundary

- [o] elsewhere[8]

Orthography

In addition to the Americanist orthography of Davis & Saunders used in this article for clarity, Nuxalk also has a non-diacritical Bouchard-type practical orthography that originated in Hank Nater's The Bella Coola Language (1984), and was used in his 1990 Nuxalk-English Dictionary. It continues to be used today at Acwsalcta for Nuxalk language learning, as well as in Nuxalk documents and names.[9] The orthographic variants are summarized below.

| Phoneme | Americanist | Practical |

|---|---|---|

| a | a | a |

| xʲ | x | c |

| xʷ | xʷ | cw |

| h | h | h |

| i | i | i |

| kʲʰ | k | k |

| kʼʲ | k̓ | k' |

| kʷʰ | kʷ | kw |

| kʼʷ | k̓ʷ | kw' |

| l | l | l |

| ɬ | ł | lh |

| m | m | m |

| n | n | n |

| pʰ | p | p |

| pʼ | p̓ | p' |

| qʰ | q | q |

| qʼ | q̓ | q' |

| qʷʰ | qʷ | qw |

| qʼʷ | q̓ʷ | qw' |

| s | s | s |

| tʰ | t | t |

| tʼ | t̓ | t' |

| t͡ɬʰ | ƛ | tl |

| t͡ɬʼ | ƛ̓ | tl' |

| t͡sʰ | c | ts |

| t͡sʼ | c̓ | ts' |

| u | u | u |

| w | w | w |

| χ | x̣ | x |

| χʷ | x̣ʷ | xw |

| j | y | y |

| ʔ | ʔ | 7 |

Syllables

The notion of syllable is challenged by Nuxalk in that it allows long strings of consonants without any intervening vowel or other sonorant. Salishan languages, and especially Nuxalk, are famous for this. For instance, the following word contains only obstruents:

- clhp'xwlhtlhplhhskwts'

- [xɬpʼχʷɬtʰɬpʰɬːskʷʰt͡sʼ]

- xłp̓χʷłtłpłłskʷc̓

- /xɬ-pʼχʷɬt-ɬp-ɬɬ-s=kʷt͡sʼ/

- possess-bunchberry-plant-PAST.PERFECT-3sSUB/3sOBJ=then

- 'then he had had in his possession a bunchberry plant.'

- (Nater 1984, cited in Bagemihl 1991: 16)

Other examples are:

- [pʰs] 'shape, mold'

- [pʼs] 'bend'

- [pʼχʷɬtʰ] 'bunchberry'

- [t͡sʰkʰtʰskʷʰt͡sʰ] 'he arrived'

- [tʰt͡sʰ] 'little boy'

- [skʷʰpʰ] 'saliva'

- [spʰs] 'northeast wind'

- [tɬʼpʰ] 'cut with scissors'

- [st͡sʼqʰ] 'animal fat'

- [st͡sʼqʰt͡sʰtʰx] 'that's my animal fat over there'

- [sxs] 'seal fat'

- [tʰɬ] 'strong'

- [qʼtʰ] 'go to shore'

- [qʷʰtʰ] 'crooked'

- [kʼxɬːtʰsxʷ.sɬχʷtʰɬːt͡s] 'you had seen that I had gone through a passage' (Nater 1984, p. 5)

There has been some dispute as to how to count the syllables in such words, what, if anything, constitutes the nuclei of those syllables, and if the concept of 'syllable' is even applicable to Nuxalk. However, when recordings are available, the syllable structure can be clearly audible, and speakers have clear conceptions as to how many syllables a word contains. In general, a syllable may be C̩, CF̩ (where F is a fricative), CV, or CVC. When C is a stop, CF syllables are always composed of a plain voiceless stop (pʰ, tʰ, t͡sʰ, kʰ, kʷ, qʰ, qʷ) plus a fricative (s, ɬ, x, xʷ, χ, χʷ). For example, płt 'thick' is two syllables, pʰɬ.t, with a syllabic fricative, while in tʼχtʰ 'stone', stʼs 'salt', qʷtʰ 'crooked', k̓ʰx 'to see' and ɬqʰ 'wet' each consonant is a separate syllable. Stop-fricative sequences can also be disyllabic, however, as in tɬ 'strong' (two syllables, at least in the cited recording) and kʷs 'rough' (one syllable or two). Syllabification of stop-fricative sequences may therefore be lexicalized or a prosodic tendency. Fricative-fricative sequences also have a tendency toward syllabicity, e.g. with sx 'bad' being one syllable or two, and sχs 'seal fat' being two syllables (sχ.s) or three. Speech rate plays a role, with e.g. ɬxʷtʰɬt͡sʰxʷ 'you spat on me' consisting of all syllabic consonants in citation form (ɬ.xʷ.tʰ.ɬ.t͡sʰ.xʷ) but condensed to stop-fricative syllables (ɬxʷ.tɬ.t͡sʰxʷ) at fast conversational speed.[10] This syllabic structure may be compared with that of Miyako.

The linguist Hank Nater has postulated the existence of a phonemic contrast between syllabic and non-syllabic sonorants: /m̩, n̩, l̩/, spelled ṃ, ṇ, ḷ. (The vowel phonemes /i, u/ would then be the syllabic counterparts of /j, w/.)[11] Words claimed to have unpredictable syllables include sṃnṃnṃuuc 'mute', smṇmṇcaw '(the fact) that they are children'.[12]

Grammar

Events

The first element in a sentence expresses the event of the proposition. It inflects for the person and number of one (in the intransitive paradigm) or two (in the transitive paradigm) participants.

| Intr. inflection | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| First Person | -c | -(i)ł |

| Second Person | -nu | -(n)ap |

| Third Person | -Ø or -s | -(n)aw |

E.g. ƛ̓ikm-Ø ti-wac̓-tx 'the dog is running'.

Whether the parenthesized segments are included in the suffix depends on whether the stem ends in an underlying resonant (vowel, liquid, nasal) and whether it is non-syllabic. So qāχla 'drink' becomes qāχla-ł 'we drink', qāχla-nap 'you (pl.) drink', qāχla-naw 'they drink', but nuyamł 'sing' becomes nuyamł-ił 'we're singing', nuyamł-ap 'you (pl.) are singing', nuyamł-aw 'they're singing'.

However, the choice of the 3ps marker -Ø or -s is conditioned by semantics rather than phonetics. For example, the sentences tix-s ti-ʔimlk-tx and tix-Ø ti-ʔimlk-tx could both be glossed 'it's the man', but the first is appropriate if the man is the one who is normally chosen, while the second is making an assertion that it is the man (as opposed to someone else, as might otherwise be thought) who is chosen.[further explanation needed]

The following are the possible person markers for transitive verbs, with empty cells indications non-occurring combinations and '--' identifying semantic combinations which require the reflexive suffix -cut- followed by the appropriate intransitive suffix:

| Transitive inflection |

Experiencer: | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | ||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| Executor | Sg | 1 | -- | -cinu | -ic | -tułap | -tic | ||

| 2 | -cxʷ | -- | -ixʷ | -tułnu | -tixʷ | ||||

| 3 | -cs | -ct | -is | -tułs | -tap | -tis | |||

| Pl | 1 | -tułnu | -ił | -- | -tułap | -tił | |||

| 2 | -cap | -ip | -tułp | -- | -tip | ||||

| 3 | -cant | -ct | -it | -tułt | -tap | -tit | |||

E.g. sp̓-is ti-ʔimlk-tx ti-stn-tx 'the man struck the tree'.

Whether a word can serve as an event isn't determined lexically, e.g. ʔimmllkī-Ø ti-nusʔūlχ-tx 'the thief is a boy', nusʔūlχ-Ø ti-q̓s-tx 'the one who is ill is a thief'.

There is a further causative paradigm whose suffixes may be used instead:

| Transitive inflection |

Experiencer: | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | ||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| Executor | Sg | 1 | -- | -tuminu | -tuc | -tumułap | -tutic | ||

| 2 | -tumxʷ | -- | -tuxʷ | -tumułxʷ | -tutixʷ | ||||

| 3 | -tum | -tumt | -tus | -tumułs | -tutap | -tutis | |||

| Pl | 1 | -tumułnu | -tuł | -- | -tumułap | -tutił | |||

| 2 | -tumanp | -tup | -tumułp | -- | -tutip | ||||

| 3 | -tumant | -tumt | -tut | -tumułt | -tutap | -tutit | |||

This has a passive counterpart:

| Passive Causative | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| First Person | -tuminic | -tuminił |

| Second Person | -tumt | -tutap |

| Third Person | -tum | -tutim |

This may also have a benefactive gloss when used with events involving less activity of their participant (e.g. nuyamł-tus ti-ʔimlk-tx ti-ʔimmllkī-tx 'the man made/let the boy sing'/'the man sang for the boy'), while in events with more active participants only the causative gloss is possible. In the later group even more active verbs have a preference for the affix-lx- (implying passive experience) before the causative suffix.

The executor in a transitive sentence always precedes the experiencer. However, when an event is proceeded by a lone participant, the semantic content of the event determines whether the participant is an executor or an experiencer. This can only be determined syntactically if the participant is marked by the preposition ʔuł-, which marks the experience.

Some events are inherently transitive or intransitive, but some may accept multiple valencies (e.g. ʔanayk 'to be needy'/'to want [something]').

Prepositions may mark experiencers, and must mark implements. Any participants which are not marked by prepositions are focussed. There are three voices, which allow either the executor, the experiencer, or both to have focus:

- Active voice - neither is marked with prepositions.

- Passive voice - the event may have different suffixes, and the executor may be omitted or marked with a preposition

- Antipassive voice - the event is marked with the affix -a- before personal markers, and the experiencer is marked with a preposition

The affix -amk- (-yamk- after the antipassive marker -a-) allows an implement to have its preposition removed and to be focused. For example:

- nuyamł-Ø ti-man-tx ʔuł-ti-mna-s-tx x-ti-syut-tx 'the father sang the song to his son'

- nuyamł-amk-is ti-man-tx ti-syut-tx ʔuł-ti-mna-s-tx 'the father sang the song to his son'

Prepositions

There are four prepositions which have broad usage in Nuxalk:

| Prepositions | Proximal | Distal |

|---|---|---|

| Stative | x- | ʔał- |

| Active | ʔuł- | wixłł- |

Deixis

Nuxalk has a set of deictic prefixes and suffixes which serve to identify items as instantiations of domains rather than domains themselves and to locate them in deictic space. Thus the sentences wac̓-Ø ti-ƛ̓ikm-tx and ti-wac̓-Ø ti-ƛ̓ikm-tx, both 'the one that's running is a dog', are slightly different - similar to the difference between the English sentences 'the visitor is Canadian' and 'the visitor is a Canadian' respectively.[18]

The deixis system has a proximal/medial/distal and a non-demonstrative/demonstrative distinction. Demonstratives may be used when finger pointing would be appropriate (or in distal space when something previously mentioned is being referred to).

Proximal demonstrative space roughly corresponds to the area of conversation, and proximal non-demonstrative may be viewed as the area in which one could attract another's attention without raising one's voice. Visible space beyond this is middle demonstrative, space outside of this but within the invisible neighborhood is medial non-demonstrative. Everything else is distal, and non-demonstrative if not mentioned earlier.

The deictic prefixes and suffixes are as follows:

| Deictic Suffixes |

Proximal | Medial | Distal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Demon- strative |

Demon- strative |

Non-Demon- strative |

Demon- strative |

Non-Demon- strative |

Demon- strative | |

| Masculine | -tx | -t̓ayx | -ł | -t̓aχ | -tχ | -taχ |

| Feminine | -cx | -c̓ayx | -ł | -ʔiłʔaył | -ʔił | -ʔił |

| Plural | -c | -ʔac | -ł | -t̓aχʷ | -tχʷ | -tuχ |

Female affixes are used only when the particular is singular and identified as female; if not, even if the particular is inanimate, masculine or plural is used.

The deictic prefixes only have a proximal vs. non-proximal distinction, and no demonstrative distinction:

| Deictic Prefixes |

Proximal | Medial and Distal |

|---|---|---|

| Masculine | ti- | ta- |

| Feminine | ci- | ła- (ʔił-) |

| Plural | wa- | ta- (tu-) |

tu- is used in earlier varieties and some types of narratives, except for middle non-demonstrative, and the variant ʔił- may be used "in the same collection of deictic space".

While events are not explicitly marked for tense per se, deixis plays a strong role in determining when the proposition is being asserted to occur. So in a sentence like mus-is ti-ʔimmllkī-tx ta-q̓lsxʷ-t̓aχ 'the boy felt that rope', the sentence is perceived as having a near-past (same day) interpretation, as the boy cannot be touching the rope in middle space from proximal space. However this does not hold for some events, like k̓x 'to see'.[21]

A distal suffix on any participant lends the event a distant past interpretation (before the past day), a medial suffix and no distal suffix lends a near past time, and if the participants are marked as proximal the time is present.

Not every distal participant occurs in past-tense sentences, and vice versa—rather, the deictic suffixes must either represent positions in space, time, or both.

Pronouns

Personal pronouns are reportedly nonexistent but the idea is expressed via verbs that translate as "to be me", etc.[22]

| Pronouns[23] | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| First person | ʔnc | łmił |

| Second person | ʔinu | łup |

| Third person | tix,cix | wix |

Particles

| Particle | Label | Gloss |

|---|---|---|

| kʷ | Quotative | 'he said' |

| ma | Dubitative | 'maybe' |

| ʔalu | Attemptive | 'try' |

| ck | Inferential Dubitative | 'I figure' |

| cakʷ | Optative | 'I wish/hope' |

| su | Expectable | 'again' |

| tu | Confirmative | 'really' |

| ku | Surprisative | 'so' |

| lu | Expective | 'expected' |

| a | Interrogative | [yes/no questions] |

| c̓ | Perfective | 'now' |

| c̓n | Imperfective | 'now' |

| k̓ʷ | Usitative | 'usually' |

| mas | Absolutive | 'always' |

| ks | Individuative | 'the one' |

| łū | Persistive | 'still, yet' |

| tū | Non-contrastive conjunction |

'and' |

| ʔi...k | Contrastive conjunction |

'but' |

See also

- Coast Salish languages

- Interior Salish

References

- Ignace, Marianne; Ignace, Ronald Eric (2017). Secwépemc people, land, and laws = Yerí7 re Stsq̓ey̓s-kucw. Montreal: McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. ISBN 978-0-7735-5203-6. OCLC 989789796.

- Nuxalk at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- Yorkton This Week, March 6th, 2021,https://www.yorktonthisweek.com/news/conklin-linguist-one-of-the-last-fluent-speakers-of-endangered-nuxalk-language-1.24279713

- Canadian Geographic magazine, November/December 2018, p.19, https://www.canadiangeographic.ca/article/resurgence-nuxalk

- Suttles, Wayne (1990), "Introduction". In "Northwest Coast", ed. Wayne Suttles. Vol. 7 of Handbook of North American Indians, ed. William C. Sturtevant, p.15.

- John R. Swanton, The Indian Tribes of North America, Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 145—1953

- Nater 1984, p. xvii

- Nater 1984, p. 5

- "Acwsalcta School".

- James Hoard (1978) "Syllabification in Northwest Indian Languages", in Bell & Bybee-Hooper (eds.) Syllables and Segments, p. 67–68.

- Nater 1984, p. 3

- Nater 1984, p. 14

- Davis & Saunders 1997, p. 24.

- Davis & Saunders 1997, p. 26.

- Davis & Saunders 1997, p. 29.

- Davis & Saunders 1997, p. 43.

- Davis & Saunders 1997, p. 36.

- Davis & Saunders 1997, pp. 83–84.

- Davis & Saunders 1997, p. 86.

- Davis & Saunders 1997, p. 89.

- Davis & Saunders 1997, pp. 89–90.

- Nater, H.F. 1984. The Bella Coola Language. Ottawa: National Museums of Canada. Cited in Bhat, D.N.S. 2004. Pronouns. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 26

- Davis & Saunders 1997, p. 114.

- Davis & Saunders, p. 180.

Bibliography

- Bruce Bagemihl (1991). "Syllable Structure in Bella Coola". Proceedings of the New England Linguistics Society. 21: 16–30.

- Bruce Bagemihl (1991). "Syllable Structure in Bella Coola". Linguistic Inquiry. 22: 589–646.

- Bruce Bagemihl (1998). Maximality in Bella Coola (Nuxalk). In E. Czaykowska-Higgins & M. D. Kinkade (Eds.), Salish Languages and Linguistics: Theoretical and Descriptive Perspectives (pp. 71–98). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Laurie Bauer, 2007, The Linguistics Student’s Handbook, Edinburgh.

- Philip W. Davis & Ross Saunders (1973). "Lexical Suffix Copying in Bella Coola". Glossa. 7: 231–252.

- Philip W. Davis & Ross Saunders (1975). "Bella Coola Nominal Deixis". Language. Language, Vol. 51, No. 4. 51 (4): 845–858. doi:10.2307/412696. JSTOR 412696.

- Philip W. Davis & Ross Saunders (1976). "Bella Coola Deictic Roots". International Journal of American Linguistics. 42 (4): 319–330. doi:10.1086/465436. S2CID 145541460.

- Philip W. Davis & Ross Saunders (1978). Bella Coola Syntax. In E.-D. Cook & J. Kaye (Eds.), Linguistic Studies of Native Canada (pp. 37–66). Vancouver: University of British Columbia.

- H. F. Nater (1979). "Bella Coola Phonology". Lingua. 49 (2–3): 169–187. doi:10.1016/0024-3841(79)90022-6.

- Philip W. Davis & Ross Saunders (1980). Bella Coola Texts. British Columbia Provincial Museum Heritage Record (No. 10). Victoria: British Columbia Provincial Museum. ISBN 0-7718-8206-8.

- Philip W. Davis & Ross Saunders (1997). A Grammar of Bella Coola. University of Montana Occasional Papers in Linguistics (No. 13). Missoula, MT: University of Montana. ISBN 1-879763-13-3.

- Forrest, Linda. (1994). The de-transitive clauses in Bella Coola: Passive vs. inverse. In T. Givón (Ed.), Voice and Inversion (pp. 147–168). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

- Mithun, Marianne. (1999). The Languages of Native North America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-23228-7 (hbk); ISBN 0-521-29875-X.

- Montler, Timothy. (2004–2005). (Handouts on Salishan Language Family).

- Nater, Hank F. (1977). Stem List of the Bella Coola language. Lisse: Peter de Ridder.

- Nater, Hank F. (1984). The Bella Coola Language. Mercury Series; Canadian Ethnology Service (No. 92). Ottawa: National Museums of Canada.

- Nater, Hank F. (1990). A Concise Nuxalk–English Dictionary. Mercury Series; Canadian Ethnology Service (No. 115). Hull, Quebec: Canadian Museum of Civilization. ISBN 0-660-10798-8.

- Newman, Stanley. (1947). Bella Coola I: Phonology. International Journal of American Linguistics, 13, 129-134.

- Newman, Stanley. (1969). Bella Coola Grammatical Processes and Form Classes. International Journal of American Linguistics, 35, 175-179.

- Newman, Stanley. (1969). Bella Coola Paradigms. International Journal of American Linguistics, 37, 299-306.

- Newman, Stanley. (1971). Bella Coola Reduplication. International Journal of American Linguistics, 37, 34-38.

- Newman, Stanley. (1974). Language Retention and Diffusion in Bella Coola. Language in Society, 3, 201-214.

- Newman, Stanley. (1976). Salish and Bella Coola Prefixes. International Journal of American Linguistics, 42, 228-242.

- Newman, Stanley. (1989). Lexical Morphemes in Bella Coola. In M. R. Key & H. Hoenigswald (Eds.), General and Amerindian Ethnolinguistics: In Remembrance of Stanley Newman (pp. 289–301). Contributions to the Sociology of Language (No. 55). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 0-89925-519-1.

External links

- Nuxalk Nation Website

- First Nations Languages of British Columbia Nuxalk page

- Nuxalk bibliography

- Nuxalk information at LanguageGeek.

- UCLA Archive for Bella Coola

- Bella Coola (Intercontinental Dictionary Series)

На других языках

- [en] Nuxalk language

[fr] Nuxalk (langue)

Le nuxalk (prononciation : /nuχalk/), également appelé bella coola, est une langue amérindienne parlée par le peuple des Nuxalk, vivant à Bella Coola et dans ses alentours, en Colombie-Britannique. Elle appartient à la famille des langues salish.[it] Lingua bella coola

La lingua Bella Coola anche conosciuta come lingua Nuxalk, appartiene alla famiglia linguistica delle Lingue salish parlata nelle vicinanze della città canadese di Bella Coola in Columbia Britannica dalla popolazione dei Nuxalk. In realtà, benché l'etnia conti 1660 persone, ormai solo meno di una ventina di essi parlano correntemente la lingua ed altri 510 la capiscono ma la parlano con difficoltà (dati 2014)[2], per cui la lingua è da considerare in via d'estinzione.[ru] Нухалк

Нухалк (белла-кула, беллакула) — один из салишских языков, на котором сейчас говорят 17 пожилых людей в окрестностях канадского города Белла Кула (Британская Колумбия). До недавнего времени язык назывался белла-кула, но сейчас предпочтительно самоназвание нухалк[2]. Хотя язык преподаётся в школах Британской Колумбии и племени нухалк, число свободно владеющих им не увеличивается.Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии