lingvo.wikisort.org - Language

Squamish (/ˈskwɔːmɪʃ/;[2] Sḵwx̱wú7mesh sníchim, sníchim meaning "language") is a Coast Salish language spoken by the Squamish people of the Pacific Northwest. It is spoken in the area that is now called southwestern British Columbia, Canada, centred on their reserve communities in Squamish, North Vancouver, and West Vancouver. An archaic historical rendering of the native Sḵwx̱wú7mesh is Sko-ko-mish but this should not be confused with the name of the Skokomish people of Washington state. Squamish is most closely related to the Sechelt, Halkomelem, and Nooksack languages.

| Squamish | |

|---|---|

| Sḵwx̱wú7mesh sníchim | |

| Pronunciation | [sqʷχʷoʔməʃ snit͡ʃim] |

| Native to | Canada |

| Region | British Columbia |

| Ethnicity | 4,280 Squamish people (2018, FPCC)[1] |

Native speakers | 1 (2014, FPCC)[1] |

| Revival | 449 Active Language Learners |

Language family | Salishan

|

Writing system | Latin (Sḵwx̱wú7mesh alphabet) |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | squ |

| Glottolog | squa1248 |

| ELP | Sḵwx̱wú7mesh sníchim (Squamish) |

Squamish Territory is shown on the map. | |

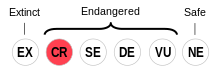

Squamish is classified as Critically Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

Documentation

| Part of a series on the |

| Squamish people |

|---|

|

| General information |

|

| Population |

| 3,893 approx. |

| Communities |

|

| Related peoples |

| Tsleil-Waututh, Musqueam, Shishalh, Nooksack, Coast Salish |

Anthropologists and linguists who have worked on the Squamish language go back to the 1880s. The Squamish Language was initially an oral language without an official written writing system, after some time a written system was formed.[3] The first collection of words was collected by German anthropologist Franz Boas. During the following decade, anthropologist Charles Hill-Tout collected some Squamish words, sentences and stories. In the 1930s, anthropologist Homer Barnett worked with Jimmy Frank to collect information about traditional Squamish culture, including some Squamish words. In the 1950s, Dutch linguist Aert H. Kuipers worked on the first comprehensive grammar of the Squamish language, later published as The Squamish Language (1967). In 1968, the British Columbia Language Project undertook more documentation of the Squamish language and culture. Randy Bouchard and Dorothy Kennedy, the main collaborators on this project, devised the writing system presently used for Squamish. It uses a modified Latin script termed Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (1990).[4] The Squamish-English bilingual dictionary (edited by Peter Jacobs and Damara Jacobs) was published by the University of Washington Press in 2011.

Use and language revitalization efforts

In 1990, the Chief and Council of the Squamish people declared Squamish to be the official language of their people, a declaration made to ensure funding for the language and its revitalization.[5] In 2010, the First Peoples’ Heritage, Language and Culture Council considered the language to be "critically endangered" and "nearly extinct", with just 10 fluent speakers.[6] In 2011, the language was being taught using the "Where Are Your Keys?" technique,[7] and a Squamish–English dictionary was also completed in 2011.

A Squamish festival was scheduled for April 22, 2013, with two fluent elders, aiming to inspire more efforts to keep the language alive. Rebecca Campbell, one of the event's organizers, commented:

"The festival is part of a multi-faceted effort to ensure the language's long-term survival, not only by teaching it in the schools, but by encouraging parents to speak it at home. Squamish Nation cultural workers, for example, have begun to provide both parents and children with a list of common Squamish phrases that can be used around the home, as a way to reinforce the learning that takes place in the Sea to Sky School District schools. So far 15 families in the Squamish area are part of the program ... 'The goal is to revive the language by trying to have it used every day at home — getting the parents on board, not just the children.'"[8]

Currently, there are 449 Active Language Learners of the Squamish language.[9] In 2014, a Squamish-language program was made available at Capilano University.[10] The program, Language and Culture Certificate, is designed to let its respective students learn about the language and culture. Additionally, Simon Fraser University has launched the Squamish Language Academy, in which students learn the Squamish language for two years. The aforementioned programs increase the number of active language learners each year.

Phonology

Vowels

The vowel system in Squamish phonemically features four sounds, /i/, /a/, /u/, as well as a schwa sound /ə/, each with phonetic variants.[11] There is a fair amount of overlap between the vowel spaces, with stress and adjacency relationships as main contributors. The vowel phonemes of Squamish are listed below in IPA with the orthography following it.[citation needed]

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | i ⟨i⟩ | u ⟨u⟩ | |

| Open-mid | ə ⟨e⟩ | ||

| Low | a ⟨a⟩ |

Vowel variants[12]

/i/ has four main allophones [e, ɛ, ɛj, i], which surface depending on adjacency relationships to consonants, or stress.

- [ɛ] surfaces preceding uvulars consonants, and can exist in a non-adjacent relationship so long as no other vowels intervene. [ɛj] surfaces proceeding a uvular consonant, before a non-uvular consonant.

- [e] surfaces in non-uvular environments when /i/ is in stressed syllables.

/a/ has four main allophones [ɛ, æ, ɔ, ɑ].

- [ɛ, æ] surfaces when palatals are present (with the exception of /j/

- [ɔ] surfaces when labial/labialized consonants are present (with the exception of /w/.

- [a] surfaces when not in the prior conditions. Stress usually does not change the vowel.

/u/

- [o] surfaces in stressed syllables.

Consonants

The consonant phonemes of Squamish, first in IPA and then in the Squamish orthography: [12]

| Labial | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | sibilant | lateral | plain | labial | plain | labial | |||||

| Plosive/ Affricate |

plain | p ⟨p⟩ | t ⟨t⟩ | t͡s ⟨ts⟩ | t͡ʃ ⟨ch⟩ | (k ⟨k⟩) | kʷ ⟨kw⟩ | q ⟨ḵ⟩ | qʷ ⟨ḵw⟩ | ʔ ⟨7⟩ | |

| ejective | pʼ ⟨pʼ⟩ | tʼ ⟨tʼ⟩ | t͡sʼ ⟨tsʼ⟩ | t͡ɬʼ ⟨tlʼ⟩ | t͡ʃʼ ⟨chʼ⟩ | (kʼ ⟨kʼ⟩) | kʷʼ ⟨kwʼ⟩ | qʼ ⟨ḵʼ⟩ | qʷʼ ⟨ḵwʼ⟩ | ||

| Fricative | s ⟨s⟩ | ɬ ⟨lh⟩ | ʃ ⟨sh⟩ | xʷ ⟨xw⟩ | χ ⟨x̱⟩ | χʷ ⟨x̱w⟩ | h ⟨h⟩ | ||||

| Sonorant | plain | m ⟨m⟩ | n ⟨n⟩ | l ⟨l⟩ | j ⟨y⟩ | w ⟨w⟩ | |||||

| glottalized | m̰ ⟨m̓⟩ | n̰ ⟨n̓⟩ | l̰ ⟨l̓⟩ | j̰ ⟨y̓⟩ | w̰ ⟨w̓⟩ | ||||||

Modifiers

Other symbols include the glottal stop and stress marks.

⟨ʔ⟩ or 7 represent a glottal stop. Glottalization can occur on a variety of consonants (w, y, l, m, n), and after or before vowels.

Orthography

The following table shows the vowels and consonants and their respective orthographic symbols. Vowels marked with an asterisk indicate phonological variation. Consonants are sorted by place (bilabial to uvular descending) and voicing (Left - Voiceless, Right - Voiced). Note that, Squamish contains no voiced plosives, as is typical of Salish language family languages. Because the /ʔ/ character glyph is not found on typewriters and did not exist in most fonts until the widespread adoption of Unicode, the Squamish orthography still conventionally represents the glottal stop with the number symbol 7; the same character glyph is also used as a digit to represent the number seven.

The other special character is a stress mark, or accent (á, é, í or ú). This indicates that the vowel should be realized as louder and slightly longer.[4]

| Phoneme | Orthography | Phoneme | Orthography |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vowels[12] | |||

| /i/ | i | /ɪ/ | i |

| */ɛ/ | i | /e/ | i |

| */æ/ | a | */ɛj/ | i |

| /u/ | u | */ʊ/ | u |

| */o/ | u | */ɔ/ | u |

| /ə/ | e | */ʌ/ | e |

| /a/ | a | */ɑ/ | ao |

| Consonants | |||

| /p/ | p | /m/ | m |

| /pʼ/ | p̓ | /ˀm/ | m̓ |

| /t/ | t | /n/ | n |

| /tɬʼ/ | t’ | /ˀn/ | n̓ |

| /tʃ/ | ts | /ɬ/ | lh |

| /tsʼ/ | ts̓ | /z/ | z |

| /k/ | k | /zʼ/ | z̓ |

| /kʷ/ | kw | /h/ | h |

| /kʼ/ | k' | /j/ | y |

| /kʷʼ/ | k̓w | /j̰/ | y̓ |

| /q/ | ḵ | /l/ | l |

| /qʷ/ | ḵw | /l̰/ | l' |

| /qχʼ/ | ḵw | ||

| /qχʷʼ/ | ḵwʼ | ||

| /ʔ/ | ʔ/7 | ||

| /ʃ/ | sh | ||

| /s/ | s | ||

| /χ/ | x̱ | ||

| /xʷ/ | xw | ||

Grammar

Squamish, like other Salish languages, has two main types of words: Clitics and full words. Clitics can be articles, or predicative clitics. Squamish words are able to be subjected to reduplication, suffixation, prefixation. A common prefix is the nominalizer prefix /s-/, which occurs in a large number of fixed combinations with verb stems to make nouns (e.g: /t'iq/ "to be cold" -> /s-t'iq/ "(the) cold").

Reduplication

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2018) |

Squamish uses a variety of reduplication types, serving to express functions such as pluralization, diminutive form, aspect, etc.

Syntax

Squamish sentences follow a Verb-Subject-Object form (the action precedes the initiator and the initiator of an action precedes the goal). Sentences typically begin with a predicate noun, but may also begin with a transitive, intransitive, or passive verb.

The table below summarizes the general order of elements in Squamish. Referents are nominal.

| Order: | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noun (predicate) | Subject | ||||

| Verb (intransitive) | R2 (other referent related term) | Subject | R1(referant related term) | ||

| Verb (Transitive) | Subject | Object | |||

| Verb (Passive) | R1(Initiator of action) | Subject | R2 (other referent related term) |

See also

- Squamish Nation

- History of Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh longshoremen, 1863–1963

References

- Squamish at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- Bauer, Laurie (2007). The Linguistics Student’s Handbook (PDF). Edinburgh.

- "How To Read The Squamish Language – KAS". Retrieved 2022-11-13.

- "How to Read the Squamish Language". Kwi Awt Stelmexw. 10 Dec 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- Baker-Williams, Kirsten (August 2006). "Squamish Language Revitalization: From the Hearts and the Minds of the Language Speakers" (PDF). University of British Columbia. p. 34. Retrieved March 12, 2012.

- "Report on the Status of B.C. First Nations Languages 2010" (PDF). First Peoples’ Heritage, Language and Culture Council. 2010. p. 64. Retrieved March 12, 2012.

- Holloway, Tessa (October 11, 2011). "Squamish Nation struggles to preserve a threatened language". North Shore News. Retrieved 2012-12-02.

- Burke, David (2013-04-18). "Squamish language festival set : Skwxúʔmesh-speaking elders help inspire effort to ensure tongue's long-term survival". Squamish Chief, Squamish, BC. Retrieved 2013-04-25.

- Dunlop, Britt; et al. (2018). Report on the Status of B.C. First Nations Languages (PDF). First Peoples' Cultural Council. ISBN 978-0-9868401-9-7.

- Wood, Stephanie (2014-01-22). "Despite limited resources, indigenous-language programs persevere in B.C." Georgia Straight, Vancouver's News & Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2014-02-27.

- Kuipers, Aert H. (1967). The Squamish language: Grammar, Texts, Dictionary. Netherlands: Mouton & Co., The Hague.

- Dyck, Ruth Anne (2004-06-04). Prosodic and Morphological Factors in Squamish (Sḵwx̱wú7mesh) Stress Assignment (PDF). University of Victoria. pp. 6, 33.

Bibliography

- Bar-el, Leora (1998). Verbal Plurality and Adverbial Quantification: A Case Study of Skwxú7mesh (Squamish). MA thesis, University of British Columbia.

- Bar-el, Leora (2005). Aspectual Distinctions in Skwxwú7mesh. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Linguistics, University of British Columbia.

- Bar-el, Leora (2005). Minimal and Maximal Events. Proceedings of WSCLA 10. S. Armoskaite, and J. Thompson (eds.). UBCWPL 17: 29-42.

- Bar-el, Leora, Henry Davis, and Lisa Matthewson (2005). On Non-Culminating Accomplishments. Proceedings of the 35th NELS Conference. L. Bateman, and C. Ussery (eds.). Amherst, MA: GLSA.

- Bar-el, Leora, Peter Jacobs, and Martina Wiltschko (2001). A [+Interpretable] Number Feature in Squamish Salish. Proceedings of WCCFL 20, Karine Megerdoomian and Leora Bar-el (eds.). USC, Los Angeles, 43-55.

- Bar-el, Leora, and Linda T. Watt (1998). What Determines Stress in Skwxwú7mish (Squamish)? ICSNL 33: 407-427, Seattle, Washington.

- Bar-el, Leora, and Linda T. Watt (2001). Word Internal Constituency in Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish Salish). Proceedings of WSCLA 5. S. Gessner, S. Oh, and K. Shiobara (eds.). UBCWPL 5: 3-18.

- Burton, Strang, Henry Davis, Peter Jacobs, Linda Tamburri Watt, and Martina Wiltschko (2001). ‘A Boy, a Dog, and a Frog. "ICSNL" 36. UBCWPL 6: 37-54.

- Currie, Elizabeth (1996). Five Sqwuxwu7mish Futures. Proceedings of the International Conference on Salishan and Neighboring Languages 31: 23-28.

- Darnell, Michael (1990). Squamish /-m/ Constructions, Berkeley Linguistics Society 16: 19-31.

- Darnell, Michael (1997). A Functional Analysis of Voice in Squamish. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

- Davis, Stuart (1984a). Moras, Light Syllable Stress and Stress Clash in Squamish. WCCFL 3: 62-74.

- Davis, Stuart (1984b). Squamish Stress Clash. Coyote Papers: Studies on Native American Languages, Japanese and Spanish, (S. Davis ed.). Tucson: University of Arizona, 2-18.

- Demers, Richard and George Horn (1978). Stress Assignment in Squamish, International Journal of American Linguistics 44: 180-191.

- Déchaine, Rose-Marie, and Martina Wiltschko (2002). The Position of Negation and its Consequences. Proceedings of WSCLA 7 (L. Bar-el, L. Watt, and I. Wilson, eds.). UBCWPL 10:29-42.

- Demirdache, Hamida, Dwight Gardiner, Peter Jacobs and Lisa Matthewson (1994). The Case for D-Quantification in Salish: 'All' in St'át'imcets, Squamish, and Secwepmectsin, Papers for the 29th International Conference on Salish and Neighboring Languages, 145-203. Pablo, Montana: Salish Kootenai College.

- Dyck, Ruth Anne (2004). Prosodic and Morphological Factors in Squamish (Sḵwx̱wú7mesh) Stress Assignment. Dissertation for University of Victoria. Retrieved (PDF) on January 7, 2017.

- Galloway, Brent (1996). An Etymological Analysis of the 59 Squamish and Halkomelem Place Names on Burrard Inlet Analyzed in Suttles Report of 1996. [Material filed in evidence in the land claims cases of Mathias vs. HMQ, Grant, and George; Grant vs. HMQ and Mathias; and George vs. HMQ and Mathias.]

- Gillon, Carrie (1998). Extraction from Skwxwú7mesh relative clauses. Proceedings of the 14th Northwest Linguistics Conference, eds. K.-J. Lee and M. Oliveira, 11-20.

- Gillon, Carrie (2001). Negation and Subject Agreement in Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish Salish). Workshop on the Structure and Constituency of the Languages of the Americas 6. Memorial University of Newfoundland, March 23–25, 2001.

- Gillon, Carrie (2006). DP structure and semantic composition in Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish). Proceedings of the North East Linguistic Society 35, eds. L. Bateman and C. Ussery, 231-244.

- Gillon, Carrie (2006). Deictic features: evidence from Skwxwú7mesh determiners and demonstratives. UBCWPL, Papers for the International Conference on Salish and Neighbouring Languages (ICSNL) 41, eds. M. Kiyota, J. Thompson and N. Yamane-Tanaka, 146-179.

- Gillon, Carrie (2009). Deictic Features: Evidence from Skwxwú7mesh, International Journal of American Linguistics 75.1: 1-27.

- Gillon, Carrie (2013). The Semantics of Determiners: Domain Restriction in Skwxwú7mesh. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Gillon, Carrie and Martina Wiltschko (2004). Missing determiners/complementizers in wh-questions: Evidence from Skwxwú7mesh and Halq’eméylem. UBCWPL vol. 14: Papers for ICSNL 39, eds. J.C. Brown and T. Peterson.

- Jacobs, Peter (1992). Subordinate Clauses in Squamish: a Coast Salish Language. M.A. thesis, University of Oregon.

- Jacobs, Peter (1994). The Inverse in Squamish, in Talmy Givón (ed.) Voice and Inversion, 121-146. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

- Jacobs, Peter (2012). Vowel harmony and schwa strengthening in Skwxwu7mesh, Proceedings of the International Conference on Salishan and Neighboring Languages 47. UBC Working Papers in Linguistics 32.

- Jacobs, Peter et al. (eds.) (2011). Squamish-English Dictionary. University of Washington Press.

- Kuipers, Aert H. (1967). The Squamish Language. The Hague: Mouton.

- Kuipers, Aert H. (1968). The categories noun-verb and transitive-intransitive in English and Squamish, Lingua 21: 610-626.

- Kuipers, Aert H. (1969). The Squamish Language. Part II. The Hague: Mouton.

- Nakayama, Toshihide (1991). On the Position of the Nominalizer in Squamish, Proceedings of the International Conference on Salishan and Neighboring Languages 18: 293-300.

- Shipley, Dawn (1995). A structural semantic analysis of kinship terms in the Squamish language, Proceedings of the International Conference on Salishan and Neighboring Languages 30.

- Watt, Linda Tamburri, Michael Alford, Jen Cameron-Turley, Carrie Gillon and Peter Jacobs (2000). Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish Salish) Stress: A Look at the Acoustics of /a/ and /u/, International Conference on Salishan and Neighboring Languages 35: 199-217. (University of British Columbia Working Papers in Linguistics Volume 3).

External links

- Bibliography at Yinka Dene Language Institute

- "Squamish for Dummies: Cool new Squamish-English dictionary". Inside Vancouver Blog. Retrieved 2012-08-08.

- "Squamish Language.com". Retrieved 2012-08-08.

- Joi T. Arcand (2011). "Language Warrior". Pacific Rim Magazine. Retrieved 2012-08-08.

- Stelmexw, Kwi Awt (2016)."How To Read The Squamish Language". https://www.kwiawtstelmexw.com/language_resources/how-to-read-the-squamish-language/.Retrieved 2016-10-29

На других языках

- [en] Squamish language

[fr] Squamish (langue)

Le squamish (Sḵwx̱wú7mesh sníchim en squamish) est la langue originellement parlée par les populations amérindiennes squamish qui vivent au sud-ouest de la province de Colombie-Britannique au Canada.[it] Lingua squamish

La lingua squamish è una lingua salish della costa parlata in Canada, nella provincia della Columbia Britannica.[ru] Скомиш

Скомиш, сквамиш[3], (Skwxwu’mesh snichim) — салишский язык, на котором говорит народ скомиш севернее города Ванкувер на юго-западе Британской Колумбии в Канаде, по центру своих индийских резервов округа Скомиш в Британской Колумбии, округах Северный Ванкувер и Западный Ванкувер. Архаическое историческое представление названия «Sḵwx̱wú7mesh» представляет собой название «Sko-ko-mish» (скокомиш), но это не следует путать с названием народа скокомиши штата Вашингтон. Язык сквамиш тесно связан с языками нуксак, халкомелем и шашишаль. В орфографии скомиш символ 7 используется для обозначения гортанной смычки /ʔ/.Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии