lingvo.wikisort.org - Language

Enets is a Samoyedic language of Northern Siberia spoken on the Lower Yenisei within the boundaries of the Taimyr Municipality District, a subdivision of Krasnoyarsk Krai, Russia Federation. The language is moribund with only around 10 fluent speakers left;[3] the overall number of potential speakers is less than 40 individuals. All speakers are found in the generation of 50 years and older. Recent local statistics indicate that there are around 230 individuals of ethnic Enets origin. Enets belongs to the Northern branch of the Samoyedic languages, in turn a branch of the Uralic language family.[4]

| Enets | |

|---|---|

| Онэй база (Onei baza)[1] | |

| Native to | Russia |

| Region | Krasnoyarsk Krai, along the lower Yenisei River |

| Ethnicity | 260 Enets people (2010 census) |

Native speakers | 43 (2010 census)[2] |

Language family | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | Either:enf – Forest Enetsenh – Tundra Enets |

| Glottolog | enet1250 |

| ELP | |

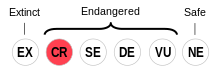

Forest Enets is classified as Critically Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

Dialects

There are two distinct dialects, Forest Enets (Bai) and Tundra Enets (Madu or Somatu), which may be considered separate languages.

Forest Enets is the smaller of the two Enets dialects. In the winter of 2006/2007, approximately 35 people spoke it (6 in Dudinka, 20 in Potapova and 10 in Tukhard, the youngest of whom was born in 1962 and the oldest in 1945). Many of these speakers are trilingual, with competence in Forest Enets, Tundra Nenets and Russian, preferring to speak Tundra Nenets.

The two dialects differ both in phonology and in lexicon. Additional variation was found in early Enets records from the 17th to 19th centuries, though all these varieties can be assigned as either Tundra Enets or Forest Enets.[5]

Phonological differences:

- In some words, Forest Enets /s/ corresponds to Tundra Enets /ɟ/ (from Proto-Samoyedic *ms, *ns, *rs and *rkʲ).

- Forest mese — Tundra meɟe 'wind' (from *merse < *märkʲä);

- Forest osa — Tundra uɟa 'meat' (from *ʊnsa < *əmså);

- Forest sira — Tundra silra 'snow';

- Forest judado — Tundra judaro 'pike';

- Forest kadaʔa — Tundra karaʔa 'grandmother';[6]

- In some words, Forest Enets word-initial /na/ corresponds to Tundra Enets /e/ (from Proto-Samoyedic *a- > *ä-).

- Certain vowel + glide sequences of Proto-Samoyedic have different reflexes in Forest Enets and Tundra Enets.

- Forest Enets word-initial /ɟi/ corresponds to Tundra Enets /i/.

Lexical differences:

- Forest eba — Tundra aburi 'head'

- Forest baða — Tundra nau 'word'

- Forest ʃaru — Tundra oma 'tobacco'

- Forest abbua — Tundra miʔ 'what'[6]

Orthography

Enets is written using the Cyrillic alphabet, though it includes the letters ԑ, ӈ, and ҫ which are not used in the Russian alphabet.

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ԑ ԑ |

| Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й | К к | Л л | М м | Н н |

| Ӈ ӈ | О о | П п | Р р | С с | Ҫ ҫ | Т т | У у |

| Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ҍ ъ | Ы ы |

| Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

The written form of the Enets language was created during the 1980s and has been used to produce a number of books. During the 1990s there was an Enets newspaper, Советский Таймыр (Soviet Taimyr) published and brief Enets broadcasts on local radio, which shut down in 2003,[7] served as supplements for speakers.[8]

Phonology

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: This section should use IPA and provide a key for the non-IPA symbols which are used in all other sections. (July 2021) |

Phoneme Inventory

The following phonemes are combined from all of the different dialects of the Enets languages;

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | i | ɨ | u |

| Mid | e, ɛ | ə | o, ɔ |

| Low | ɑ | ||

Consonants

| Labial | Dental | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | pal. | plain | pal. | plain | pal. | ||||

| Nasal | m | mʲ | n | nʲ | ŋ | ||||

| Stop/ Affricate |

voiceless | p | pʲ | t | tʲ | t͡ʃ | t͡ʃʲ | k | ʔ |

| voiced | b | bʲ | d | dʲ | g | ||||

| Fricative | plain | ð | x | h | |||||

| sibilant | s | sʲ | ʃ | ʃʲ | |||||

| Trill | r | rʲ | |||||||

| Approximant | w | l | lʲ | j | |||||

- There is partial or complete vowel reduction in the middle and at the end of a word

- Consonants preceding i and e become palatalized[9]

Uralist transcription

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | unrounded | unrounded | rounded | |

| High | i | i̮ | u | |

| Mid | e | e̮ | ȯ | |

| Low | ɑ | o | ||

Vowel length is indicated by a macron, e.g. ē [eː].

Consonants

| bilabial | dental | palatal | velar | laryngeal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plosives | p, b | t, d | t', d' | k, g | ʔ |

| affricates | č | č' | |||

| fricatives | s, š, δ | ś, š' | h | ||

| nasals | m | n | ń | ŋ | |

| laterals | l | ||||

| trills | r | ||||

| glides | w | j |

Stress

The type of stress in Enets is quantitative. Stressed vowels are pronounced relatively longer than unstressed vowels. Based on the available data, the stress is not (as a rule) used as a feature for distinguishing the meaning. The stress in a word usually falls on the first vowel. The primary stress usually falls on the first syllable and is accompanied by a secondary stress, which falls on the third and the fifth syllable. Sometimes the stress distinguishes the meaning, e.g. in mo·di ('I') vs. modi· ('shoulder'). (The primary stress is marked by ·).[6]

Morphology

The parts of speech in Enets are: nouns, adjectives, numerals, pronouns, verbs, adverbs, postpositions, conjunctions, interjections and connective particles.[6]

The grammatical number is expressed by means of the opposition of the singular, dual and plural forms. There are three declensions, the main (non-possessive), possessive and desiderative declensions, and seven cases in Enets: the nominative, genitive, accusative, lative, locative, ablative and prolative case. The meaning of those cases is expressed by means of suffixes added to nouns, adjectives, pronouns and substantivized verbs. In their fixed forms they also belong to adverbs and postpositions. The possession is expressed by means of the genitive case or possessive suffixes.[6]

Local orientation is based on the three-member distribution: the suffixes of local cases of nouns, adverbs and postpositions are divided among the lative (to where?), locative (where?) and ablative (from where?). The prolative case (along what? or through what?) expresses an additional fourth local characteristic.

The verbal negation is expressed by the combination of the main verb with a preceding auxiliary negative verb. The auxiliary verb is conjugated according to general rules, but the main verb is in a special inconjugated negative form. There are also some verbs of absence - non-possessiveness. Six moods are contrasted in the Enets language: indicative, conjunctive, imperative, optative, quotative and interrogative. There are three tenses: aorist, preterite and future. [6]

The category of person with nouns is expressed by means of possessive suffixes, differing in all three numbers of all three persons and used in nouns, pronouns, substantivized verbs, adverbs and postpositions. The category of person with verbs is expressed by means of particular personal suffixes of the verb, differing in all three numbers of all three persons.

There are three conjugations in Enets: subjective, objective and reflexive. These conjugations differ from each other by personal suffixes. Additionally, the objective conjugation uses numerical suffixes, referring to all three numbers of the object. In the case of the reflexive conjugation, the person of the subject and object is the same and a separate suffix indicates reflexivity.[6]

Nouns

Depending on the final sounds of the word stem, nouns can be divided into two groups:

- nouns with a final sound other than a laryngal plosive stop, e.g. d'uda 'horse'

- nouns with a final laryngal plosive stop, e.g. tauʔ 'Nganasan'

Either group uses variants of suffixes with a different initial sound (e.g. Loc d'uda-han, tau-kon).

There are seven cases in Enets: the nominative, genitive, accusative, lative, locative, ablative and prolative case. The case suffixes are combined with numeral markers, often in a fairly complex manner.[6]

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| Nominative | - | -ʔ |

| Genitive | -ʔ | -ʔ |

| Accusative | - | -ʔ |

| Lative | -d/-t | -hi̮δ/-gi̮δ/-ki̮δ |

| Locative | -hVn/-gon/-kon | -hi̮n/-gi̮n/-ki̮n |

| Ablative | -hVδ/-gi̮δ/-ki̮δ | -hi̮t/-gi̮t/-ki̮t |

| Prolative | -on/-mon | -i̮n/-on |

The dual case forms are produced on the basis of an uninflected dual form with the suffix -hi̮ʔ/-gi̮ʔ/-ki̮ʔ by adding the respective singular case endings of some postpositions (mainly nə-) in local cases.[6]

Adjectives

There are a number of adjectives that have no specific suffixes, e.g. utik 'bad', sojδa 'good', lodo 'low' and piδe 'high'.

Alongside of these there are various suffixal adjectives, e.g. buse̮-saj ne̮ 'a married woman', bite-δa 'waterless', uδa-šiδa 'handless', mȯga-he 'belonging to the forest', same-raha 'wolf-like', narδe-de̮ 'red', polδe-de̮ 'black'.

An adjective does not agree with the following main word either in number or case, e.g. agga koja 'big sterlet', agga koja-hone (locative), agga koja-hi̮t (plural ablative). As an exception , we can refer to the use of the adjective instead of an elliptical noun and as a predicate in the nominal conjugation.

With the aim of strengthening a possessive connection, sometimes a respective possessive suffix may be added to the main word of an attribute, e.g. keδerʔ koba-δa ŋul'ʔ mujuʔ 'the wild reindeer skin is very strong' ("its-skin of-the-wild-reindeer...").

The comparative degree is formed by means of an adjective in the positive degree (in the nominative form) with the word to be compared in the ablative form.[6]

Numerals

Cardinals

1. ŋōʔ

2. siδe

3. nehuʔ

4. teto

5. sobboreggo

6. mottuʔ

7. seʔo

8. sidiʔeto

9. nēsā

10. biwʔ

11. ŋoʔbodade

12. side bodade

13. nehuʔ bodade

14. teto bodade

20. sidiuʔ

21. sidiuʔ ŋōʔ

30. nehibiʔ

40. tetujʔ

50. sobboreggujʔ

60. motujʔ

70. seʔujʔ

80. siδetujʔ

90. nēsauʔ

100. juʔ[6]

Ordinals

1. orδede̮

2. ne̮kujde̮

3. ne̮hode̮

4. tetode̮

5. sobode̮

6. motode̮

7. se̮ʔode̮

8. siδetode̮

9. ne̮satode̮

10. biwde̮

100. d'urde̮[6]

Other numerals

Collective numerals are formed combining a separate word namely a form e̮š of the auxiliary verb 'to be' with cardinal numerals, e.g. siδe e̮š 'we two, the two of us'.

Distributive numerals are postpositional constructions of cardinals, combined with the postposition loδ, e.g. siδeʔ loδ 'by (in) twos'.

Iteratives are the plural forms of cardinals, e.g. ŋobuʔ 'one time, once'.

Fractional numerals are cardinals that are combined with the word boʔ 'a half', e.g. nehuʔ boʔ 'one-third'.

Temporal numerals are formed from cardinals by means of the suffix -ʔ, e.g. orδede̮ʔ 'the first time'.[6]

Pronouns

Personal Pronouns

Two-member constructions are used are used in declining personal pronouns. The second member of these constructions is either an independent word stem si- or a postpositional stem no-. The first member may be lacking.[6]

Case Singular Dual Plural Nominative modi, mod' 'I' modiniʔ 'we two' modinaʔ 'we' Genitive mod' siń modińʔ siδińʔ modinaʔ siδnaʔ Accusative mod' siʔ modińʔ siδińʔ modinaʔ siδnaʔ Lative mod' noń modińʔ nońʔ modinaʔ nonaʔ Locative mod' none̮ń modińʔ none̮ńʔ modinaʔ nonnaʔ Ablative mod' noδoń modińʔ noδońʔ modinaʔ noδnaʔ Prolative mod' noone̮ń modińʔ noone̮ńʔ modinaʔ noone̮naʔ

Case Singular Dual Plural Nominative ū 'you' ūdiʔ 'you two' ūdaʔ 'you' Genitive ū sit ūdiʔ siδtiʔ ūdaʔ siδtaʔ Accusative ū sit ūdiʔ siδδiʔ ūdaʔ siδδaʔ Lative ū nod ūdiʔ nodiʔ ūdaʔ nodaʔ Locative ū none̮d ūdiʔ nondiʔ ūdaʔ nondaʔ Ablative ū noδod ūdiʔ noδdiʔ ūdaʔ noδdaʔ Prolative ū noone̮d ūdiʔ noone̮diʔ ūdaʔ noone̮daʔ

Case Singular Dual Plural Nominative bu 'he/she' budiʔ 'they two' buduʔ 'they' Genitive bu sita budiʔ sitiʔ buduʔ siδtuʔ Accusative bu sita budiʔ siδδiʔ buduʔ siδδuʔ Lative bu noda budiʔ nodiʔ buduʔ noduʔ Locative bu nonda budiʔ nondiʔ buduʔ nonduʔ Ablative bu noδda budiʔ noδdiʔ buduʔ noδduʔ Prolative bu noone̮da budiʔ noone̮diʔ buduʔ noone̮duʔ

Other Pronouns

Reflexive pronouns are pairs of words whose first component consists of personal pronouns, the second is a separate word stem ker-, combined with their respective possessive suffixes, e.g. mod' keriń 'I myself', ū kerit 'you yourself', bu kerta 'she herself/he himself' or modiń keriń 'we two ourselves'.

Interrogative pronouns are kurse̮ 'which?', sēa 'who?' (used only for humans) and obu 'what?' (used for animals and lifeless objects).

Negative pronouns are formed from interrogative pronouns by adding the suffix -hȯru, e.g. obuhȯru.[6]

Verbs

The verbs in Enets can be distributed into two groups in principally the same manner as the noun depending on the final sounds of the word stem. Either group uses the variants of suffixes with different initial sounds.

Seven moods are contrasted: indicative, conjunctive, imperative, optative, quotative and interrogative. There are three tenses: aorist, preterite and future. (These tenses exist practically only in the indicative mood.) The verb has three conjugations: subjective, objective and reflexive. These conjugations differ from each other by personal suffixes. In addition to this the objective conjugation uses numerical suffixes, referring to all three numbers of the object. In the case of reflexive conjugation a separate suffix indicates reflexivity.[6]

Finite forms

The aorist is either unmarked or with the marker -ŋV-/-V-. The temporal meaning of the aorist depends on the aspect of the verb. A prolonged or recurrent action should be understood as taking place in the present, a short-time or single action as having taken place in the past, whereas the influence of the latter is still felt in the present. A distinctly past action is expressed by the preterite with the marker -ś/-š/-d'/-t'/-č, whereas the marker is placed after personal suffixes. The future action is expressed by the future marker -d-/-dV-/-t-/-tV- before personal suffixes.

The objective conjugation uses one type of personal suffixes when the object is in the singular and another type of them with the object in the dual or the plural. In the case of the dual object the dual marker -hu-/-gu-/-ku- precedes the dual personal suffixes of the second type, whereas in the case of the plural object, the rise of the stem vowel can be observed. The marker of the reflexive mood is -i-, which is standing before personal suffixes.[6]

Syntax

The syntax of Enets is typical for the family and the area. The Enets language follows Subject-object-verb, head marking in the noun phrase, both head and dependent marking within the clause, non-finite verbal forms used for clause combining. Consequently, the finite verb form (the predicate) is always at the end of a sentence. The negative auxiliary verb immediately precedes the main verb. The object of a sentence always keeps to the word it belongs to.[6]

Grammar

Enets nouns vary for number, case, and person-number of the possessor. There is also an intriguing nominal case in which ‘destinativity’ determines the entity is destined for someone. Possessor markers are also used for discourse related purposes, where they are completely devoid of the literal possessive meaning. Enets postpositions are marked for person-number; many postpositions are formed from a small set of relational nouns and case morphology.[10]

Literature

- Künnap, Ago (1999). Enets. München: Lincom Europa.

- Haig, G. L., Nau, N., Schnell, S., & Wegener, C. (2011). Achievements and Perspectives. Documenting Endangered Languages, 119-150. doi:10.1515/9783110260021.vii

- Khanina, O. (2018). Documenting a language with phonemic and phonetic variation: the case of Enets. Language Documentation & Conservation 12. 430-460. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24772

- Khanina, O., & Shluinsky, A. (2008). Finites structures in Forest Enets subordination: A case study of language change under strong Russian influence. Subordination and Coordination Strategies in North Asian Languages Current Issues in Linguistic Theory, 63-75. doi:10.1075/cilt.300.07kha

- Khanina, O., & Shluinsky, A. (2013). Choice of case in cross-reference markers: Forest Enets non-finite forms. Finnisch-Ugrische Mitteilungen Band, 37, 32-44. Retrieved from http://iling-ran.ru/Shluinsky/ashl/ChoiceOfCase_2013.pdf

- Khanina, Olesya; Shluinsky, Andrey (2014). "A rare type of benefactive construction: Evidence from Enets". Linguistics. 52 (6): 1391–1431. doi:10.1515/ling-2014-0025.

- Mikola T.: Morphologisches Wörterbuch des Enzischen. Szeged, 1995 (= Studia Uralo-Altaica 36)

- Siegl, F. (2012). More on Possible Forest Enets – Ket Contacts. Eesti ja Soome-Ugri Keeleteaduse Ajakiri, 3(1), 327-341. doi:10.12697/jeful.2015.6.3.00

- Siegl, F. (2012). Yes/no questions and the interrogative mood in Forest Enets . Per Urales ad Orientem. Iter polyphonicum multilingue, 399-408. Retrieved from http://www.sgr.fi/sust/sust264/sust264_siegl.pdf

- Siegl, Florian (2013). Materials on Forest Enets, an Indigenous Language of Northern Siberia (PDF). (Mémoires de la Société Finno-Ougrienne, 267). Helsinki: Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran Toimituksia. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- Siegl, F. (2015). Negation in Forest Enets. Negation in Uralic Languages Typological Studies in Language, 43-74. doi:10.1075/tsl.108.02sie

- Vajda, E. J. (2008). Subordination and Coordination Strategies in North Asian Languages. Current Issues in Linguistic Theory, 63-73. doi:10.1075/cilt.300

- Болина, Д. С.: Русско-энецкий разговорник. Санкт-Петербург: Просвещение, 2003, 111p. ISBN 5-09-005269-7

- Сорокина, И. П.; Болина, Д .С.: Энецкий-русско и русско-энецкий словарь. Санкт-Петербург: Просвещение, 2001, 311p. ISBN 5-09-002526-6

- Сорокина, И. П.; Болина, Д .С.: Энецкие тексты. Санкт-Петербург: Наука, 2005, 350 p.. ISBN 5-02-026381-8. Online version.

- Сорокина, И. П.; Болина, Д. С.: Энецкий словарь с кратким грамматическим очерком: около 8.000 слов. Санкт-Петербург: Наука 2009, 488p. ISBN 978-5-98187-304-1

- Сорокина, И. П.: Энецкий язык. Санкт-Петербург: Наука 2010, 411p. ISBN 978-5-02-025581-4

References

- Сорокина, И. П.; Болина, Д. С. (2001). Словарь энецко-русский и русско-энецкий [Enets-Russian and Russian-Enets dictionary]. Санкт-Петербург: Филиал издательства «Просвещение». p. 310. ISBN 5-09-002526-6.

- "Population of the Russian Federation by Languages (in Russian)" (PDF). gks.ru. Russian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- "Enets, Forest _ Ethnologue - Forest Enets.pdf". Google Docs. Retrieved 2022-07-07.

- Siegl, F. (2013). Materials on Forest Enets, an indigenous language of Northern Siberia. Tartu. doi:978-9949-19-673-9, http://dspace.ut.ee/handle/10062/17439?locale-attribute=en

- Helimskij, Eugen (1985). "Die Feststellung der dialektalen Zugehörigkeit der encischen Materialen". Dialectologia Uralica: Materialien des ersten Internationalen Symposions zur Dialektologie der uralischen Sprachen 4.-7. September 1984 in Hamburg. Veröffentlichungen der Societas Uralo-Altaica. ISBN 3-447-02535-2.

- Künnap, Ago (1999). Enets.

- Siegl, Florian (2017-04-24). "The fate of Forest Enets – a short comm ent".

- "Enets language, alphabet and pronunciation". www.omniglot.com.

- "Enf/Phonology - ProAlKi". proalki.uni-leipzig.de.

- Leipzig, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. "Former Dept. of Linguistics | Documentation of Enets". www.eva.mpg.de.

External links

- Enets bibliography

- Bibliography on Enets studies

- Linguistic items (Texts, vocabularies, links, ...)

- ELAR archive of Enets language documentation materials

- http://www.siberianlanguages.surrey.ac.uk/summary/

На других языках

[de] Enzische Sprache

Die enzische Sprache (in Eigenbezeichnung Enets) ist eine der samojedischen Sprachen. Diese bilden gemeinsam mit den finno-ugrischen Sprachen die uralische Sprachfamilie. Es gehört wie Nenzisch und Nganasanisch zur Gruppe der nordsamojedischen Sprachen. Es gibt zwei Varianten des Enzischen, die manchmal als eigene Sprachen gewertet werden: Wald-Enzisch (auch Bai) und Tundra-Enzisch (auch Maddu).- [en] Enets language

[fr] Énètse

L'énètse est une langue samoyède du Nord de même que le nénètse et le nganassan, parlée par 40 personnes du peuple énètse (recensement de 2010). Elle descend comme toutes les langues samoyèdes du proto-samoyède (en) dont elle a commencé à se séparer dans la seconde moitié du premier millénaire, et se divise en deux dialectes qui peuvent être considérés comme des langues séparées : l'énètse de la toundra ou maddu et l'énètse des forêts ou baj (en 1995, le premier comptait 30 locuteurs, le second 40), qui diffèrent assez profondément au niveau du vocabulaire. L'énètse est parlé le long du fleuve Ienisseï, en aval de Dudinka, notamment dans la réserve de Potapovo pour l'énètse des forêts et dans celle de Vorontzovo pour l'énètse de la toundra. Le lexique a été influencé par le nganassan (vocabulaire de la chasse) et par le nénètse (vocabulaire de l'élevage de rennes), ainsi que par d'autres langues, dans une moindre mesure. La langue est de type agglutinant et grammaticalement très proche de ses « sœurs » (énètse, nénètse, et nganassan ont d'ailleurs la même étymologie).[it] Lingua enets

La lingua enets,[1][2] chiamata anche samoiedo dello Enisej,[1][3] è una lingua samoieda parlata in Russia dal popolo degli Enets o Enci, che vivono nella Siberia occidentale.[ru] Энецкий язык

Э́нецкий язы́к — язык энцев; один из самодийских языков уральской языковой семьи, распространённый на правобережье нижнего течения Енисея в Таймырском районе. Число говорящих на энецком языке — 43 чел. (2010 г.). В 2002 году таких было 119 чел.Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии