lingvo.wikisort.org - Language

Ingrian (ižoran keeli [ˈiʒorɑŋ ˈkeːli] or inkeroin keeli IPA: [ˈiŋkeroi̯ŋ ˈkeːli]), also called Izhorian, is a nearly extinct Finnic language spoken by the (mainly Orthodox) Izhorians of Ingria. It has approximately 120 native speakers left, all of whom are elderly.[1]

| Ingrian | |

|---|---|

| ižoran keeli | |

| Native to | Russia |

| Region | Ingria |

| Ethnicity | 1,143 Izhorians |

Native speakers | 120 (2010 census)[1] |

Language family | |

Writing system | Latin |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | izh |

| Glottolog | ingr1248 |

| ELP | Ingrian |

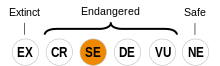

Ingrian is classified as Severely Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger (2010) | |

The Ingrian language should be distinguished from the Ingrian dialect of the Finnish language, which became the majority language of Ingria in the 17th century with the influx of Lutheran Finnish immigrants; their descendants, the Ingrian Finns, are often referred to as Ingrians. The immigration of Lutheran Finns was promoted by Swedish authorities, who gained the area in 1617 from Russia, as the local population was (and remained) Orthodox.

Classification

Ingrian is classified, together with Finnish, Karelian (including Livvi), Ludic and Veps, in the Northern Finnic branch of the Uralic languages.

History

In 1932–1937, a Latin-based orthography for the Ingrian language existed, taught in schools of the Soikino Peninsula and the area around the mouth of the Luga River.[2] Several textbooks were published, including in 1936 a grammar of the language. However, in 1937 the Izhorian written language was abolished and mass repressions of the peasantry began.[2]

Alphabet (1932)[3]

| A a | Ä ä | E e | F f | H h | I i | J j | K k |

| L l | M m | N n | O o | Ö ö | P p | R r | S s |

| T t | U u | V v | Y y | B b | G g | D d | Z z |

Alphabet (1936)

The order of the 1936 alphabet is similar to the Russian Cyrillic alphabet.

| A a | Ä ä | B в | V v | G g | D d | E e | Ƶ ƶ |

| Z z | I i | J j | K k | L l | M m | N n | O o |

| Ö ö | P p | R r | S s | T t | U u | Y y | F f |

| H h | C c | Ç ç | Ş ş | ь |

Alphabet (2005–present)

The order of the current alphabet matches the Finnish alphabet.

| A a | B b | C c | D d | E e | F f | G g | H h |

| I i | J j | K k | L l | M m | N n | O o | P p |

| R r | S s | Š š | T t | U u | V v | Y y | Z z |

| Ž ž | Ä ä | Ö ö |

Dialects

Four dialects groups of Ingrian have been attested, two of which are probably extinct by now:[4][5]

- Hevaha, spoken along Kovashi River and nearby coastal areas (†)

- Soikkola, spoken on Soikinsky Peninsula and along Sista River

- Ylä-Laukaa (Upper Luga or Oredezhi), spoken along Orodezh River and the upper Luga River (†)

- Ala-Laukaa (Lower Luga), a divergent dialect influenced by Votic

A fifth dialect may have once been spoken on the Karelian Isthmus in northernmost Ingria, and may have been a substrate of local dialects of southwestern Finnish.[4]

Grammar

Like other Uralic languages, Ingrian is a highly agglutinative language.

There is some controversy between the grammars as described by different scholars. For example, Chernyavskij (2005) provides the form on ("he/she is") as the only possible third-person singular indicative of the verb olla ("to be"), while the native speaker Junus (1936) as well as Konkova (2014) describe also the form ono.

Nouns

Ingrian nouns have two numbers: yksikkö (singular) and monikko (plural). Both numbers can be inflected in eleven grammatical cases:[6][7][8]

| Case | Yksikkö ending |

Monikko ending |

Meaning/use | Example (singular, plural) | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic/grammatical cases | |||||

| Nominativa | ∅ | -t | Subject | škoulu, škoulut | school(s) |

| Genetiva | -n | -in | Possession | škoulun, škouluin | school's, schools' |

| Partitiva | -a | -ia | Partial object, Amount | škoulua, škouluja | school(s) |

| Interior ("in") locative cases | |||||

| Illativa | -V | -i(he) | Motion into | škouluu, škouluihe | into (a) school(s) |

| Inessiva | -(V)s | -is | Location inside | škouluus, škouluis | inside (a) school(s) |

| Elativa | -st | -ist | Motion out of | škoulust, škouluist | out of (a) school(s) |

| Exterior ("on") locative cases | |||||

| Allativa | -lle | -ille | Motion onto | škoululle, škouluille | onto [the top of] (a) school(s) |

| Adessiva | -(V)l | -il | Location on top of | škouluul, škouluil | on [top of] (a) school(s) |

| Ablativa | -lt | -ilt | Motion off | škoulult, škouluilt | off [the top of] (a) school(s) |

| Essive cases | |||||

| Translativa | -ks | -iks | Change of state towards being | škouluks, škouluiks | into being (a) school(s) |

| Essiva | -nna, -(V)n | -inna, -in | State of being | škoulunna [škouluun], škouluinna [škouluin] | as (a) school(s) |

| Eksessiva | -nt | -int | Change of state away from being | škoulunt, škouluint | out of being (a) school(s) |

- Following the vowel harmony, ⟨a⟩ can change into ⟨ä⟩.

- Some cases are (partially) written with ⟨V⟩. The symbol stands for the vowel on which the preceding stem ends.

- The orthography used by Chernyavskij (2005) uses the letter -z for the inessive.

Ingrian doesn't have a separate accusative case. This case corresponds with the genitive (in the singular) and the nominative (in the plural).

Ingrian also has a high amount of compound words. In these words, the last word of the compound is inflected:

- sana (word) + kirja (book) = sanakirja (dictionary, nominativa), sanakirjan (genetiva), sanakirjaa (partitiva)

Like other Finnic languages, Ingrian nouns don't have gender. However, Ingrian does have a few gender-specific suffixes:

- ižoran (Ingrian); ižorakkoi (Ingrian woman); ižoralain (Ingrian man).

- juuti (Jew); juutakkoi (Jewish woman); juutalain (Jewish man).

Adjectives

Adjectives don't differ from nouns morphologically, that is to say that they are inflected the same as nouns. Adjectives are always attributed to a noun, either directly or with the verb olla (to be).

Comparatives are formed by adding the suffix -mp to the Genitive stem. It is then inflected as usual:

- vanha (old, nominativa); vanhan (old, genetiva); vanhemp (older, nominativa); vanhemman (older, genetiva).

The object of the comparison will be set in the partitiva:

- vanhemp äijä (the older grandpa); vanhemp äijää (older than a grandpa)

Superlatives are formed by adding the partitiva of the pronoun kaik:

- vanhemp (older); kaikkia vanhemp (oldest); vanhemp kaikkia (older than all)

Verbs

Infinitives

The Ingrian verbs have two infinitives, both of which can be inflected (much like the nouns) depending on the situation of usage.

The first infinitive comes in the partitiva or inessiva. The partitiva of the first infinitive is used after the verbs kyssyyä (to ask), pyytää (to ask), alkaa (to start), tahtoa (to want), suvata (to love), vässyyä (to tire) and pittää (to have to):

- Tahon läätä. (I want to talk.)

The inessiva of the first infinitive acts as a present participle. It denotes an action that happens simultaneously with the acting verb:

- Höö männää läätes. (They walk, talking.)

The second infinitive comes in the illativa, inessiva, elativa and abessiva. The illativa of the second infinitive is used to denote a reported act (e.g. after the verb nähhä, to see), to denote a purpose or following the verbs männä (to go), lähtiä (to go) or noissa (to come to pass):

- Nään hänt läkkäämää. (I see that he talks.)

- Issuu läkkäämää. (Sit in order to talk.)

- Hää noisi läkkäämää. (He began talking.)

The inessiva of the second infinitive acts as a continuous clause, introduced by the verb olla (to be). It denotes an action that is happening at the present moment:

- Miä oon läkkäämäs. (I am talking.)

The elativa of the second infinitive denotes either the completion of the action or a distancing from its location:

- Hää poistui läkkäämäst. (He left there, where he was talking.)

The abessiva of the second infinitive acts as a participle of an incomplete action:

- Hää poistui läkkäämätä. (He left not having talked.)

Voice and mood

Ingrian verbs come in three voices: Active, passive and reflexive:

- Hää pessöö (He washes [active voice]); Hää pessää (He is being washed [passive voice]); Hää pessiiää (He washes himself [reflexive voice]).

Both the active and passive voices can be portrayed by the indicative mood (both present and imperfect) and conditional mood, while the imperative can only be set in the active voice:

- Miä nään (I see [Present indicative active]); Miä näin (I saw [Imperfect indicative active]); Miä näkkisin (I would see [Conditional active]); Nää! (See [Imperative active])

- Miä nähhää (I am seen [Present indicative passive]); Miä nähtii (I was seen [Imperfect indicative passive]); Miä nähtäis (I would be seen [Conditional passive]).

Negation

Like in most other Uralic languages, Ingrian negation is formed by adding the inflected form of the verb ei (not) to the connegative of the desired verb:

- Miä oon (I am); Miä en oo (I am not)

The connegative differs depending on the tense and mood of the main verb.

- Miä en oo (I am not); Miä en olt (I was not)

The conjugation of the negative verb follows:

| Yksikko | Monikko | |

|---|---|---|

| First Person | en | emmä |

| Second Person | et | että |

| Third Person | ei | evät |

Pronouns

The personal pronouns set in nominatiivi are listed in the following table:

| Yksikko | Monikko | |

|---|---|---|

| First Person | miä | möö |

| Second Person | siä | söö |

| Third Person | hää | höö |

The demonstrative pronouns set in nominativa are listed in the following table:

| Yksikko | Monikko | |

|---|---|---|

| Personal | se | neet |

| Proximal | tämä (tää) | nämät (näät) |

| Distal | too | noo |

The proximal demonstrative pronouns tämä and nämät can be contracted to tää and näät respectively. Furthermore, the genetiva singular form tämän can be contracted to tään. Other inflections cannot be contracted.

Phonology

Vowels

The Ingrian language has 8 vowels:

| Front | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | unrounded | rounded | |

| Close | i /i/ | y /y/ | u /u/ | |

| Mid | e /e/ | ö /ø/ | o /o/ | |

| Open | ä /æ/ | a /ɑ/ | ||

Ingrian vowels can be phonologically long and short. Furthermore, these vowels can combine into a total of 14 diphthongs.

Consonants

The Ingrian language has 22 consonant sounds:

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | voiceless | p /p/ | t /t/ | k /k/ | ||

| voiced | b /b/ | d /d/ | g /ɡ/ | |||

| Affricate | ts /t͡s/ | c /t͡ʃ/ | ||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f /f/ | s /s/ | š /ʃ/ | h /h/, /x/ | |

| voiced | z /z/ | ž /ʒ/ | ||||

| Nasal | m /m/ | n /n/ | (n /ŋ/) | |||

| Approximant | v /ʋ/ | l /l/ | j /j/ | |||

| Rhotic | r /r/ | |||||

- The consonant ⟨h⟩ is realized as [h] when short and as [xː] when long (this distinction isn't present in the Ala-Laukaa dialect).

- The consonant ⟨n⟩ is realized as [ŋ] when followed by the phoneme /k/ or /ɡ/.

- Phonetic palatalization [ʲ] may occur among different dialects before close-front vowels /i, y/.

- The voiced plosives (/b/, /d/, /ɡ/) and fricatives (/z/, /ʒ/), as well as the postalveolar fricative /ʃ/ are not phonemic in the Soikkola dialect's native words.

The Soikkola dialect has a three-way distinction of consonant length (/t/, /tˑ/, /tː/). Both the long and halflong geminates are shown double in writing (⟨tt⟩). Other dialects only differentiate between long (/tː/) and short (/t/) consonants.

Stress

Primary stress in Ingrian by rule comes on the first syllable, while the secondary stresses come on every further uneven syllable, with the exception of a final syllable.

- puu ("wood") is realized as /puː/

- kana ("chicken") is realized as /ˈkɑnɑ/

- orava ("squirrel") is realized as /ˈorɑʋɑ/

- cirkkulaiset ("sparrows") is realised as /ˈt͡ʃirkːuˌlɑi̯set/

In some late borrowings, the primary stress may shift to another syllable:

- vokala ("vowel") is realized as /ʋoˈkɑlɑ/

Morphophonology

The Ingrian language has several morphophonological processes.

Vowel harmony is the process that the affixes attached to a lemma may change depending on the stressed vowel of the word. This means that if the word is stressed on a back vowel, the affix would contain a back vowel as well, while if the word's stress lies on a front vowel, the affix would naturally contain a front vowel. Thus, if the stress of a word lies on an "a", "o" or "u", the possible affix vowels would be "a", "o" or "u", while if the stress of a word lies on an "ä", "ö" or "y", the possible affix vowels to this word would then be "ä", "ö" or "y":

- nappi (button, nominativa); nappia (button, partitiva)

- näppi (pinch, nominativa); näppiä (pinch, partitiva)

The vowels "e" and "i" are neutral, that is to say that they can be used together with both types of vowels.

References

- Ingrian at Ethnologue (24th ed., 2021)

- Kurs, Ott (1994). Ingria: The broken landbridge between Estonia and Finland. GeoJournal 33.1, 107–113.

- Duubof V. S., Lensu J. J. ja Junus V. (1932). Ensikirja ja lukukirja: inkeroisia oppikoteja vart (PDF). Leningrad: Valtion kustannusliike kirja. pp. 89 (вкладка).

- Viitso, Tiit-Rein (1998). "Fennic". In Abondolo, Daniel (ed.). Uralic languages. Routledge. pp. 98–99.

- Kuznetsova, Natalia; Markus, Elena; Mulinov, Mehmed (2015), "Finnic minorities of Ingria: The current sociolinguistic situation and its background", in Marten, H.; Rießler, M.; Saarikivi, J.; et al. (eds.), Cultural and linguistic minorities in the Russian Federation and the European Union, Multilingual Education, vol. 13, Berlin: Springer, pp. 151–152, ISBN 978-3-319-10454-6, retrieved 25 March 2015

- V Chernyavskij (2005). Ižoran keel (Ittseopastaja) (PDF). (in Russian).

- O. I. Konkova and N. A. D'yachkov (2014). Inkeroin keel: Учебное пособие по Ижорскому языку (PDF). (in Russian).

- V. I. Junus (1936). Iƶoran Keelen Grammatikka (PDF). (in Ingrian)

Bibliography

- Paul Ariste 1981. Keelekontaktid. Tallinn: Valgus. [pt. 2.6. Kolme läänemere keele hääbumine lk. 76 – 82] (in Estonian)

- A. Laanest. 1993. Ižorskij Jazyk. In V. N. Jartseva (ed.), Jazyki Mira: Ural'skie Jazyki, 55–63. Moskva: Nauka.

- V. Chernyavskij. 2005. Ižorskij Jazyk (Samuchitel'). Ms. 300pp.

External links

- V.Cherniavskij "Izoran keeli (Ittseopastaja)/Ижорский язык (Самоучитель) (Ingrian Self-Study Book")" (in Russian).

- Ingrian verb conjugation

- Ingrian language resources at Giellatekno

- INKEROIN KEEL УЧЕБНОЕ ПОСОБИЕ ПО ИЖОРСКОМУ ЯЗЫКУ

На других языках

[de] Ischorische Sprache

Ischorisch (auch: Ishorisch;[1] ižoran keeli), nach dem geografischen Gebiet Ingermanland auch Ingermanisch oder Ingrisch, ist eine stark gefährdete Sprache aus der finno-ugrischen Sprachfamilie.- [en] Ingrian language

[es] Idioma ingrio

El idioma ingrio es una lengua ugrofinesa hablada por los ingrios (en particular, ortodoxos). En el censo de 2002 se contaban unos 362 hablantes, la mayoría de ellos de edad avanzada; en el censo de 2010 aparecían sólo 120 hablantes.[fr] Ingrien

L'ingrien ou ijore, ižor, izhor (en ingrien: inkeroin keeli, en russe : ижорский язык) est une langue fennique de la famille des langues finno-ougriennes parlée en Russie.[it] Lingua ingrica

La lingua ingrica o ingriana[1] è una lingua baltofinnica parlata in Russia e nella regione storica dell'Ingria.[ru] Ижорский язык

Ижо́рский язы́к (самоназвание — ižorin kēli) — язык малочисленной народности ижора, проживающей в Ленинградской области Российской Федерации. Относится к северной группе прибалтийско-финских языков уральской языковой семьи.Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии