lingvo.wikisort.org - Language

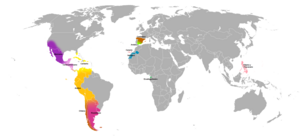

Chilean Spanish (Spanish: español chileno) is any of several varieties of the Spanish language spoken in most of Chile. Chilean Spanish dialects have distinctive pronunciation, grammar, vocabulary, and slang usages that differ from those of Standard Spanish.[2] Formal Spanish in Chile has recently incorporated an increasing number of colloquial elements.[3]

| Chilean Spanish | |

|---|---|

| Español chileno | |

| Pronunciation | [ehpaˈɲol tʃiˈleno] |

| Native to | Chile |

Native speakers | 17.4 million (2015)[1] |

Language family | |

Writing system | Latin (Spanish alphabet) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

| IETF | es-CL |

| Spanish language |

|---|

|

| Overview |

|

| History |

| Grammar |

|

| Dialects |

|

| Dialectology |

|

| Interlanguages |

|

| Teaching |

|

The Royal Spanish Academy recognizes 2,214 words and idioms exclusively or mainly produced in Chilean Spanish, in addition to many still unrecognized slang expressions.[4]

Alongside Honduran Spanish, Chilean Spanish has been identified by various linguists as one of the two most divergent varieties.[3]

Variation and accents

In Chile, there are not many differences between the Spanish spoken in the northern, central and southern areas of the country,[5] although there are notable differences in zones of the far south—such as Aysén, Magallanes (mainly along the border with Argentina), and Chiloé—and in Arica in the extreme north. There is, however, much variation in the Spanish spoken by different social classes; this is a prevalent reality in Chile given the presence of stark wealth inequality.[6] In rural areas from Santiago to Valdivia, Chilean Spanish shows the historical influence of the Castúo dialects of Extremadura (Spain),[7][8] but some authors point to the Spanish province of Andalusia and more specifically to the city of Seville as an even greater influence on the historical development of Chilean Spanish. In general, the intonation of Chilean Spanish is recognized in the Spanish-speaking world for being one of the fastest-spoken accents among Spanish dialects and with tones that rise and fall in its speech, especially in Santiago and its surroundings; such intonation may be less strong in certain areas of the north of the country and more pronounced in southern areas. It is also not uncommon that other Spanish speakers, native and otherwise, have more difficulty understanding Chilean Spanish speakers than other accents.

As result of past German immigration, there are a few German influences in the vocabulary, accent, and pronunciation of southern Chile.[9] Speakers of Chilean Spanish who also speak German or Mapudungun tend to use more impersonal pronouns (see also: Alemañol).[10] Dialects of southern Chile (Valdivia/Temuco to Chiloé) are considered to be have a melodic intonation (cantadito) relative to the speech in Santiago.[11] A survey among inhabitants of Santiago also shows that people in the capital consider southern Chilean Spanish to be variously affected by Mapudungun, have poor pronunciation, be of rural character and, in the case of Chiloé, to be rich in archaisms.[11] The same study does also show a perception that the speech of northern Chile is influenced by the Spanish spoken in Peru and Bolivia.[11]

Chile is part of a region of South America known as the Southern Cone (Spanish: Cono Sur; Portuguese: Cone Sul). The region consists of Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay; sometimes it also includes Paraguay and some regions of Brazil (Paraná, Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina, and São Paulo). The vocabulary across the region is similar for Spanish speakers, and in some cases it's also shared by the Portuguese speakers in the Southern Cone parts of Brazil.

The Chilean Spanish dialect of Easter Island, most especially the accent, is influenced by Rapa Nui language.

Phonology

There are a number of phonetic features common to most Chilean accents, but none of them is individually unique to Chilean Spanish.[12] Rather, it is the particular combination of features that sets Chilean Spanish apart from other regional Spanish dialects.[13] The features include the following:[14][15]

- Yeísmo, the historical merger of the phoneme /ʎ/ (spelled ⟨ll⟩) with /ʝ/ (spelled ⟨y⟩). For speakers with yeísmo, the verbs cayó 's/he fell' and calló 's/he fell silent' are homophones, both pronounced [kaˈʝo]. (In dialects that lack yeísmo, maintaining the historical distinction, the two words are pronounced respectively [kaˈʝo] and [kaˈʎo].) Yeísmo characterizes the speech of most Spanish-speakers both in Spain and in the Americas. In Chile, there is a declining number of speakers who maintain the distinction, mainly in some Andean areas south of Santiago.[5][16]

- Like most other American dialects of Spanish, Chilean Spanish has seseo: /θ/ is not distinguished from /s/. In much of the Andean region, the merged phoneme is pronounced as apicoalveolar [s̺],[citation needed] a sound with a place of articulation intermediate between laminodental [s] and palatal [ʃ]. That trait is associated with a large number of northern Spanish settlers in Andean Chile.[citation needed]

- Syllable-final /s/ is often aspirated to [h] or lost entirely, another feature common to many varieties of Spanish in the Americas, as well as the Canary Islands and the southern half of Spain. Whether final /s/ aspirates or is elided depends on a number of social, regional, and phonological factors, but in general, aspiration is most frequent before a consonant. Complete elision is most commonly found word-finally but carries a sociolinguistic stigma.[17] Thus, los chilenos '(the) Chileans' can be [loh tʃiˈleno].

- The velar consonants /k/, /ɡ/, and /x/ are fronted or palatalized before front vowels. Thus, queso 'cheese', guía 'guide', and jinete 'rider/horseman' are pronounced respectively [ˈceso], [ˈɟi.a], and [çiˈnete]. Also, /x/ is pronounced [h] or [x] in other phonological environments and so caja 'box' and rojo 'red' are pronounced [ˈkaxa] ~ [ˈkaha] and [ˈroxo] ~ [ˈroho] respectively. In the rest of the article, the back allophone of /x/ is transcribed with the phonemic symbol ⟨x⟩.

- Between vowels and word-finally, /d/ commonly elides or lenites, as is common throughout the Spanish-speaking world); contado 'told' and ciudad 'city' are [konˈta.o] (contao) and [sjuˈða] (ciudá) respectively. Elision is less common in formal or upper-class speech.

- The voiceless postalveolar affricate /tʃ/ is pronounced as a fricative [ʃ] by many lower-class speakers and so Chile and leche (milk) are pronounced [ˈʃile] and [ˈleʃe], respectively). That pronunciation is greatly stigmatized. Other variants are more fronted and include the alveolar affricate [ts] or an even more fronted dental affricate [t̪s̪], mostly in the upper class. Thus, Chile and leche are pronounced [ˈtsile] or [ˈletse].

- Word-final /n/ is pronounced as a velar nasal [ŋ] only in north Chilean dialects.

- Unstressed word-final vowels are often devoiced.[18]

- The phoneme represented by the letters ⟨b⟩ and ⟨v⟩ may be pronounced [v] in variation with [b] and [β]; in most other Spanish dialects, only [b] and [β] may appear as allophones of that phoneme.[19]

- Consonant cluster [tɾ] can be pronounced [tɹ̝̥] or [tɻ], making cuatro 'four' and trabajo 'work' pronounced as [ˈkwatɹ̝̥o ~ˈkwatɻo] and [tɹ̝̥aˈβaxo ~ tɻaˈβaxo] respectively. This is an influence of Mapudungun.[20]

Syntax and grammar

- Doubling the object clitics me, te, se, lo(s), la(s) and le(s) before and after the verb is common in lower-class speech. For example, 'I'm going to go' becomes me voy a irme (Standard Spanish: me voy a ir and voy a irme). 'I'm going to give them to you' becomes te las voy a dártelas.

- Queísmo (using que instead of de que) is socially accepted and used in the media, and dequeísmo (using de que instead of que) is somewhat stigmatized.

- In ordinary speech, conjugations of the imperative mood of a few of verbs tend to be replaced with the indicative third-person singular. For example, the second-person singular imperative of poner 'to put', which is pon, becomes pone; that of hacer 'to do', which is haz, becomes hace; and that of salir 'to exit', sal, becomes sale: hace lo que te pedí 'do what I asked'. However, that is not done in formal speech. Chileans also replace the etymological second-person singular imperative of the verb ir 'to go', ve, with the second-person singular imperative of andar 'to walk', anda, and ve is reserved for the verb ver 'to see': ve la hora 'look at the time'.

- Another feature to note is the lack of use of the possessive nuestro 'our', which is usually replaced by de nosotros 'of us': ándate a la casa de nosotros, literally 'go to the house of us', instead of ándate a nuestra casa 'go to our house'.

- It is very common in Chile, as in many other Latin American countries, to use the diminutive suffixes -ito and -ita. They can mean 'little', as in perrito 'little dog' or casita 'little house', but can also express affection, as with mamita 'mummy, mommy'. They can also diminish the urgency, directness, or importance of something to make something annoying seem more pleasant.[21] So, if someone says espérese un momentito literally 'wait a little moment', it does not mean that the moment will be short, but that the speaker wants to make waiting more palatable and hint that the moment may turn out to be quite long.

Pronouns and verbs

Chileans use the voseo and tuteo forms for the intimate second-person singular. Voseo is common in Chile, with both pronominal and verbal voseo being widely used in the spoken language.

In Chile there are at least four grades of formality:

- Pronominal and verbal voseo, the use of the pronoun vos (with the corresponding voseo verbs):

vos sabí(s), vos vení(s), vos hablái(s), etc.

This occurs only in very informal situations.

- Verbal voseo, the use of the pronoun tú:

tú sabí(s), tú vení(s), tú hablái(s), etc.

This is the predominant form used in the spoken language.[22] It is not used in formal situations or with people one does not know well. - Standard tuteo:

tú sabes, tú vienes, tú hablas, etc.

This is the only acceptable way to write the intimate second-person singular. Its use in spoken language is reserved for slightly more formal situations such as (some) child-to-parent, teacher-to-student, or peer-to-peer relations among people who do not know each other well. - The use of the pronoun usted:

usted sabe, usted viene, usted habla, etc.

This is used for all business and other formal interactions, such as student-to-teacher but not always teacher-to-student as well as "upwards" if one person is considered to be well respected, older or of an obviously higher social standing. Stricter parents will demand this kind of speech from their children as well.

The Chilean voseo conjugation has only three irregular verbs in the present indicative: ser 'to be', ir 'to go', and haber 'to have' (auxiliary).

Conjugation

A comparison of the conjugation of the Chilean voseo, the voseo used in Latin American countries other than Chile, and tuteo follows:

| Form | Indicative | Subjunctive | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present | Imperfect | Conditional | Present | Imperfect | |

| Voseo (Chile)[23] | caminái traí(s) viví(s) | caminabai traíai vivíai | caminaríai traeríai viviríai | caminís traigái vivái | caminarai trajerai vivierai |

| Vosotras Vosotros | camináis traéis vivís | caminabais traíais vivíais | caminaríais traeríais viviríais | caminéis traigáis viváis | caminarais trajerais vivierais |

| Voseo (general) | caminás traés vivís | caminabas traías vivías | caminarías traerías vivirías | caminés* traigás* vivás* | caminaras trajeras vivieras |

| Tuteo | caminas traes vives | camines traigas vivas | |||

* Rioplatense Spanish prefers the tuteo verb forms.[24]

A 2014 article argues that Chilean, and Rioplatense, Spanish's verb forms with vos are derived from the same underlying representations as its verb forms with tú, with a few rules applied.[23] First there is an accentuation rule which assigns stress to the syllable following the verb's base, which is either its root or the infinitive in the case of the future and conditional conjugations. Thus, the underlying representation /bailas/ becomes bailás 'you dance'. This first rule alone derives all of Rioplatense Spanish's voseo forms. Chilean Spanish then has the processes of semi-vocalization and vowel raising. In semi-vocalization, /s/ becomes the semivowel /j/ after /a/ or /o/. Thus, sos becomes soi and -as in general becomes -ai. With vowel raising, stressed /e/ becomes /i/. Thus, the underlying form /bebes/, after stress placement and vowel raising, becomes bebís 'you drink'.[23]

Chilean voseo has two different future tense conjugations: one in -ís, as in bailarís, and one in -ái, as in bailarái 'you will dance'. These come from two different underlying representations, one ending in /-es/, and the other ending in /-as/. The /-es/ representation corresponds to a historical future tense form ending in -és, as in estarés. Such a historical conjugation existed in Spain in the 15th and 16th centuries, alongside the -ás endings, and was recorded in Chile in the 17th century. All this said, the simple future tense is not actually used that often in Chile. Instead, the periphrastic future construction (ie va a...) is more common.[23]

Ser

In Chile, there are various ways to say 'you are' to one person.[23]

- Vo(s) soi

- Vo(s) erí(s)

- Tú soi

- Tú erí(s)

- Tú eres

- Usted es

Only the last two are considered Standard Spanish. Usage depends on politeness, social relationships, formality, and education. The ending (s) in those forms is aspirated or omitted.

The form erei is also occasionally found. It apparently derives from the underlying form /eres/, with the final /s/ becoming a semivowel /j/, as happens in other voseo conjugations. The more common forms soi and erís are likewise derived from the underlying representations /sos/ and /eres/.[23]

Haber

The auxiliary verb haber, most often used to form existential statements and compound tenses, has two different present indicative forms with vos in Chile: hai and habís.[23]

Ir

Ir, 'to go', can be conjugated as vai with vos in the present tense in Chile.[23]

Vocabulary

Chilean Spanish has a great deal of distinctive slang and vocabulary. Some examples of distinctive Chilean slang include al tiro (right away), gallo/a (guy/gal), fome (boring), pololear (to go out as girlfriend/boyfriend), pololo/polola (boyfriend/girlfriend),[25] pelambre (gossip), pito (marijuana cigarette i.e. joint) poto (buttocks),[26] quiltro (mutt) and chomba (knitted sweater)[25] wea (thing; can be used for an object or situation). Another popular Chilean Spanish slang expression is poh, also spelled po', which is a term of emphasis of an idea, this is a monophthongized and aspirated form of pues. In addition, several words in Chilean Spanish are borrowed from neighboring Amerindian languages.

- weón - dude/friend or stupid (it depends on the context)

- abacanao - presumptuous

- agarrar - to get in a fight

- altiro - right away

- apretao - stingy or tight

- arrastre - to have influence on others

- avisparse - to realize

- bacán - awesome

- ”cachar” - to understand

- caleta - a lot

- cana - jail

- chanchada - disloyal act/eat like a pig

- completo - hot dog

- chupar - to consume alcohol

- echar la foca (lit. throw the seal/breath) - to severely address someone or express disapproval or disappointment

- emputecer - getting mad

- engrupir - to fool or influence someone

- fome - boring

- garúa - drizzle

- hacer perro muerto (lit. do a dead dog) - to dine and dash or do something similar

- pesao - mean

- sapear - to spy or eavesdrop

Argentine and Rioplatense influence

In Chilean Spanish there is lexical influence from Argentine dialects, which suggests a covert prestige.[27] Lexical influences cut across the different social strata of Chile. Argentine summer tourism in Chile and Chilean tourism in Argentina provide a channel for influence on the speech of the middle and upper classes.[27] The majority of the population receive Argentine influence by watching Argentine programs on broadcast television, especially football on cable television[27] and music such as cumbia villera on the radio as well.[27] Chilean newspaper La Cuarta regularly employs slang words and expressions that originated in the lunfardo slang of the Buenos Aires region. Usually Chileans do not recognize the Argentine borrowings as such, claiming they are Chilean terms and expressions due to the long time since they were incorporated.[27] The relation between Argentine dialects and Chilean Spanish is one of asymmetric permeability, with Chilean Spanish adopting sayings from Argentine variants but usually not the reverse.[27] Lunfardo is an argot of the Spanish language that originated in the late 19th century among the lower classes of Buenos Aires and Montevideo that influenced "Coa", an argot common among criminals in Chile, and later colloquial Chilean Spanish.

- atorrante - tramp

- cafiche - pimp or abusive man

- arrugar- flinch

- bancar - support, tolerate, bear, hold

- trucho - fake, cheat

- canchero - expert or arrogant

- mufa - something that brings bad luck

- manga - a big group of

- punga - a pickpocket

- tira - undercover police

- yeta - 'jinx' or someone who brings bad luck

Mapudungun loanwords

The Mapudungun language has left a relatively small number of words in Chilean Spanish, given its large geographic expanse. Many Mapudungun loans are names for plants, animals, and places. For example:[30][31][32]

- cahuín:[20] a rowdy gathering; also malicious or slanderous gossip.

- copihue: Lapageria rosea, Chile's national flower.

- culpeo: the culpeo, or Andean fox, Lycalopex culpaeus.

- luma - Amomyrtus luma, a native tree species known for its extremely hard wood; also a police baton (historically made from luma wood in Chile).

- chape: braid.

- guarén: the brown rat.

- laucha: mouse.

- roquín: lunch, picnic

- cuncuna: caterpillar.

- pichintún: pinch, or very small portion.

- pilucho: naked.

- piñén: dirt of the body.

- guata: belly.

- machi: Mapuche shaman.

- colo colo: pampas cat, Leopardus colocola.

- curi: black, dark.

- curiche: dark-skinned person.

- charquicán: a popular stew dish.

- malón: military surprise attack; also, a party.

- paila: frying pan

- ulpo: non-alcoholic drink made of toasted flour and water or milk.

- pilcha: shabby suit of clothing.

- huila: shredded, ragged.

- merkén: smoked chili pepper.

- funa: a demonstration of public denunciation and repudiation against a person or group. Also to be bored or demotivated, demoralized.

- huifa: wiggle with elegance, sensuality, and grace; also, interjection to express joy.

- pichiruchi: tiny, despicable, or insignificant.

- pololo: Astylus trifasciatus, an orange-and-black-striped beetle native to Chile; also, boyfriend.

- quiltro: mongrel, or stray dog.

- ruca: hut, cabin.[33]

Quechua loanwords

The Quechua language is probably the Amerindian language that has given Chilean Spanish the largest number of loanwords. For example, the names of many American vegetables in Chilean Spanish are derived from Quechua names, rather than from Nahuatl or Taíno as in Standard Spanish. Some of the words of Quechua origin include:[30]

- callampa: mushroom; also, penis (Quechua k'allampa[34]).

- cancha: field, pitch, slope (ski), runway (aviation), running track, court (tennis, basketball)[20] (Quechua kancha[34]).

- chacra - a small farm[20] (Quechua chakra)[34]).

- chala: sandal.[20]

- chasca: tassle; diminutive chasquilla: bangs (of hair).

- china: a female servant in a hacienda.[20]

- choclo: maize/corn (Quechua chuqllu[34]).

- chúcaro: spirited/wild, used traditionally by huasos to refer to a horse.

- chupalla: a traditional Chilean straw hat.[20]

- chupe: soup/chowder (Quechua chupi[34]).

- cocaví: snack/lunch or picnic (from coca).

- cochayuyo: Durvillaea antarctica, a species of kelp[20] (Quechua qucha yuyu[34]).

- guagua: child, baby (Quechua wawa,[34]).

- guanaco: guanaco, Lama guanicoe, a native camelid mammal (Quechua wanaku[34]).

- guasca: whip (Quechua waskha).

- huacho: an orphan or illegitimate child; also, as an adjective, lone or without a mate, as in a matchless sock.

- huaso: a country dweller and horseman.[20]

- huincha: a strip of wool or cotton or a tape measure; also used for adhesive tape (Quechua wincha[34]).

- humita: an Andean dish similar to the Mexican tamale (Quechua humint'a, jumint'a[34][35]); also a bow tie.

- mate: an infusion made of yerba mate.

- mote: mote, a type of dried wheat (Quechua mut'i[34]).

- palta: avocado.

- poroto: bean (Quechua purutu[34]).

- yapa or llapa: lagniappe.

- zapallo: squash/pumpkin (Quechua sapallu[34]).

French, German and English loanwords

There are some expressions of non-Hispanic European origin such as British, German or French. They came with the arrival of the European immigrants in the 19th and 20th centuries. There is also a certain influence from the mass media.

- bufé - piece of furniture, from French buffet.

- bistec or bisté - meat, from English 'beefsteak'.

- budín - pudding, from the English 'pudding

- cachái - you understand, you see; for example, ¿Cachái?, Did you understand?, Did you see?, Did you get?; form of cachar, from English 'catch'.[36]

- chao or chau - goodbye, from Italian ciao

- chutear - to shoot, from English 'shoot'.

- clóset - closet, from English 'closet'.

- confort - toilet paper, from French confort; a brand name for toilet paper.[37]

- guachimán - ship guard, from English 'watchman'

- zapin or zaping - to change channel whilst watching TV, to channel surf, from English 'to zap'.

- jaibón - upper class, from English 'high born'.

- kuchen or cujen - A kind of fruit cake, from German Kuchen.

- lobear - to lobby, from English 'to lobby'.

- livin or living- living room, from English 'living room'.

- lumpen - lower-class people, from German Lumpenproletariat.

- luquear - to look, from English 'to look'.

- marraqueta - a kind of bread, from French Marraquette, surname of the Frenchmen who invented it.

- panqueque - pancake, from English 'pancake'.

- overol - overall, from English 'overall'.

- shorts - short trousers, from English 'short trousers'.

- strudel or estrudel - dessert, from German Strudel, a typical German and Austrian dessert.

- vestón - jacket, from French veston.

Sample

Here is sample of a normal text in carefully spoken Latin American Spanish and the same text with a very relaxed pronunciation in informal lower-class Chilean Spanish:[38]

| Text | ¡Cómo corrieron los chilenos Salas y Zamorano! Pelearon como leones. Chocaron una y otra vez contra la defensa azul. ¡Qué gentío llenaba el estadio! En verdad fue una jornada inolvidable. Ajustado cabezazo de Salas y ¡gol! Al celebrar [Salas] resbaló y se rasgó la camiseta. |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation ("Standard" Latin American Spanish) |

[ˈkomo koˈrjeɾon los tʃiˈlenoˈsalas i samoˈɾano | peleˈaɾoŋ ˈkomo leˈones | tʃoˈkaɾon ˈunajˈotɾa ˈβes ˈkontɾa la ðeˈfensaˈsul | ˈke xenˈtio ʝeˈnaβae̯l esˈtaðjo | em beɾˈðað ˈfwewna xoɾˈnaðajnolβiˈðaβle | axusˈtaðo kaβeˈsaso ðe ˈsalas i ˈɣol | al seleˈβɾarːezβaˈloj se razˈɣo la kamiˈseta] |

| Pronunciation (Chilean Spanish) |

[ˈkomo koˈrjeɾon loh ʃiˈleno ˈsalaj samoˈɾano | peˈljaɾoŋ komo ˈljoneh | ʃoˈkaɾon ˈunajˈotɹ̝̝̥a ˈʋeh kontɹ̝̥a la̯eˈfensaˈsul | ˈce çenˈtio ʝeˈnae̯l ehˈtaðjo | eɱ veɹˈða ˈfwewna xonˈnajnolʋiˈawle | axuhˈtao kaʋeˈsasoe̯ ˈsalaj ˈɣol | al seleˈvɾa ɹ̝efaˈloj se ɹ̝aˈxo la kamiˈseta] |

| Translation | "How those Chileans Salas and Zamorano ran! They fought like lions. They beat again and again against the blues' defense. What a crowd filled the stadium! In truth it was an unforgettable day. A tight header from Salas and... goal! Celebrating, Salas slid and ripped his shirt." |

See also

- Languages of Chile

- Bello orthography

- Mapudungun

- Quechua languages

References

- "Chile".

- Miguel Ángel Bastenier, "Neologismos y barbarismos en el español de dos océanos", El País, 19 July 2014, retrieved 20 July 2014. "...el chileno es un producto genuino e inimitable por el resto del universo lingüístico del español."

- Alemany, Luis (30 November 2021). "El español de Chile: la gran olla a presión del idioma". El Mundo (in Spanish). Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- "Nuevo diccionario ejemplificado de chilenismos y de otros usos diferenciales del español de Chile. Tomos I, II y III | Universidad de Playa Ancha Sello Editorial Puntángeles" (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- Canfield (1981:31)

- CLASES SOCIALES, LENGUAJE Y SOCIALIZACION Basil Bernstein, http://www.infoamerica.org/ retrieved June 25, 2013

- "CHILE - Vozdemitierra" (in Spanish). Vozdemitierra.wiki-site.com. Archived from the original on 9 February 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- "Extremadura en América - Diez mil extremeños - Biblioteca Virtual Extremeña". Paseovirtual.net. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- Wagner, Claudio (2000). "Las áreas de "bocha", "polca" y "murra". Contacto de lenguas en el sur de Chile". Revista de Dialectología y Tradiciones Populares (in Spanish). LV (1): 185–196. doi:10.3989/rdtp.2000.v55.i1.432.

- Hurtado Cubillos, Luz Marcela (2009). "La expresión de impersonalidad en el español de Chile". Cuadernos de lingüística hispánica (in Spanish). 13: 31–42.

- "Percepción y valoración de variedades geográficas del español de Chile entre hispanohablantes santiaguinos" [Perception and valuation of geographical varieties of Chilean Spanish amongst Spanish-speaking subjects from Santiago de Chile]. Boletín de filología (in Spanish). XLVII (1): 137–163. 2012.

- EL ESPAÑOL EN AMÉRICA cvc.cervantes.e - JESÚS SÁNCHEZ LOBATO - page 553-570

- Language of Chile: Chileanismos, Castellano and indigenous roots Archived 2 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine www.thisischile.cl - February 22, 2011, retrieved August 8, 2013

- Lipski (1994: 199-201)

- Sáez Godoy, Leopoldo. "El dialecto más austral del español: fonética del español de Chile". Unidad y divesidad del español, Congreso de Valladolid. Centro Virtual Cervantes. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- Oroz (1966:119)

- Lipski (1994:199)

- Lipski (1994:201)

- "Feature descriptions". Voices of the Hispanic World. Ohio State Universiy. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- Correa Mujica, Miguel (2001). "Influencias de las lenguas indígenas en el español de Chile". Espéculo. Revista de estudios literarios. (in Spanish). Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Retrieved 31 May 2009.

- Chilean Spanish & Chileanisms Archived 2006-01-12 at the Wayback Machine http://www.contactchile.cl/ retrieved June 27, 2013

- Lipski (1994: 201-2)

- Baquero Velásquez, Julia M.; Westphal Montt, Germán F. (16 July 2014). "Un análisis sincrónico del voseo verbal chileno y rioplatense". Forma y Función (in Spanish). 27 (2): 11–40. doi:10.15446/fyf.v27n2.47558.

- Real Academia Española. "voseo | Diccionario panhispánico de dudas". «Diccionario panhispánico de dudas» (in Spanish). Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- "Real Academia Española". Rae.es. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- Lipski (1994: 203)

- Salamanca, Gastón; Ramírez, Ariella (2014). "Argentinismos en el léxico del español de Chile: Nuevas evidencias". Atenea. 509: 97–121. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- Salamanca, Gastón (2010). "Apuntes sociolingüísticos sobre la presencia de argentinismos en el léxico del español de Chile". Atenea (Concepción) (502): 125–149. doi:10.4067/S0718-04622010000200008. ISSN 0718-0462.

- Salamanca, Gastón; Ramírez, Ariella (June 2014). "Argentinismos en el Léxico del Español de Chile: Nuevas Evidencias". Atenea (Concepción) (509): 97–121. doi:10.4067/S0718-04622014000100006. ISSN 0718-0462.

- Zúñiga, Fernando (11 June 2006). "Tras la huella del Mapudungun". El Mercurio (in Spanish). Centro de Estudios Publicos. Archived from the original on 29 October 2007. Retrieved 12 November 2007.

- "Día de la lengua materna: ¿Qué palabras de uso diario provienen de nuestros pueblos originarios? | Emol.com". 21 February 2017.

- "Del origen mapuche de las palabras chilenas". 2 April 2011.

- Tana de Gámez, ed., Simon and Schuster's International Dictionary English/Spanish Spanish/English (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1973)

- Teofilo Laime Ajacopa, Diccionario bilingüe iskay simipi yuyayk'ancha, La Paz, 2007 (Quechua-Spanish dictionary)

- Diccionario Quechua - Español - Quechua, Academía Mayor de la Lengua Quechua, Gobierno Regional Cusco, Cusco 2005 (Quechua-Spanish dictionary

- "18 Chilean Slang Phrases You'll Need on Your Trip".

- "Productos - Confort". www.confort.cl.

- Marcela Rivadeneira Valenzuela. "El Voseo En Medios de Comunicacion de Chile" (PDF) (in Spanish). www.tesisenxarxa.net. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2010. Pages 82-83.

Bibliography

- Canfield, D. Lincoln (1981), Spanish Pronunciation in the Americas], Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-09262-1

- Lipski, John M. (1994), Latin American Spanish, Essex, U.K.: Longman Group Limited

- Oroz, Rodolfo (1966), La lengua castellana en Chile, Santiago: Universidad de Chile

External links

- (in Spanish) Diccionario de Modismos Chilenos - Comprehensive "Dictionary of Chilean Terms".

- Pepe's Chile Chilean Slang - basic list of Chilean slang/unique colloquialisms.

- Jergas de habla hispana Spanish dictionary specializing in slang and colloquial expressions, featuring all Spanish-speaking countries, including Chile.

- Elcastellano.org

На других языках

- [en] Chilean Spanish

[fr] Espagnol chilien

L’espagnol chilien (ou castillan chilien) est une variante d'espagnol parlée sur le territoire du Chili. Ses différences avec les autres variantes ou accents d'Amérique latine concernent principalement la prononciation, la syntaxe des phrases et le vocabulaire. La variante chilienne est connue pour avoir une multiplicité de tons pour chaque situation, en plus de sa façon particulière de conjuguer le tú (tu, toi) ou vos (vous), mais ce mot est considéré comme très informel et d'un niveau inférieur de langue.[ru] Чилийский испанский

Чилийский испанский (исп. Español chileno) — национальный вариант испанского языка в Чили, отражающий нормы центрального говора Сантьяго. При этом в некоторых окраинных регионах страны сохраняются и отличные от национальной нормы диалекты (андский испанский на крайнем севере и чилотский испанский[es] на крайнем юге). Нормы чилийского испанского обычно употребляют около 17 миллионов жителей республики, а также около 1 миллиона человек, представляющих чилийскую диаспору. Чилийский испанский отличается аспирацией и/или выпадением конечной -s (дебуккализация), выпадением интервокальной и конечной -d, наличием йеизма; своеобразием интонационного рисунка и глагольной парадигмы, в которой преобладает вербальное восео при сохранении tú в качестве подлежащего. Сохранение tú произошло во многом благодаря деятельности Андресa Бельо (бывший ректор Чилийского университета), который объявил восео войну.Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии