lingvo.wikisort.org - Alphabet

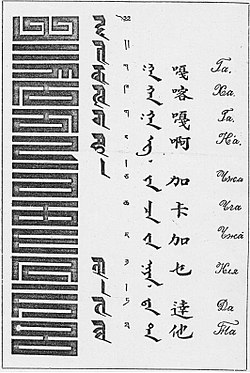

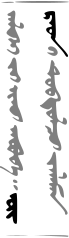

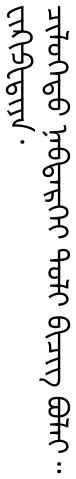

The classical or traditional Mongolian script,[note 1] also known as the Hudum Mongol bichig,[note 2] was the first writing system created specifically for the Mongolian language, and was the most widespread until the introduction of Cyrillic in 1946. It is traditionally written in vertical lines ![]() Top-Down, right across the page. Derived from the Old Uyghur alphabet, Mongolian is a true alphabet, with separate letters for consonants and vowels. The Mongolian script has been adapted to write languages such as Oirat and Manchu. Alphabets based on this classical vertical script are used in Mongolia and Inner Mongolia to this day to write Mongolian, Xibe and, experimentally, Evenki.

Top-Down, right across the page. Derived from the Old Uyghur alphabet, Mongolian is a true alphabet, with separate letters for consonants and vowels. The Mongolian script has been adapted to write languages such as Oirat and Manchu. Alphabets based on this classical vertical script are used in Mongolia and Inner Mongolia to this day to write Mongolian, Xibe and, experimentally, Evenki.

| Mongolian script ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠣᠯ ᠪᠢᠴᠢᠭ | |

|---|---|

| Script type | Alphabet

|

| Creator | Tata-tonga |

Time period | c. 1204 – present |

| Direction | vertical left-to-right, left-to-right |

| Languages | Mongolian language |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | Egyptian hieroglyphs

|

Child systems | Manchu alphabet Oirat alphabet (Clear script) Buryat alphabet Galik alphabet Evenki alphabet |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Mong (145), Mongolian |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Mongolian |

Unicode range |

|

Computer operating systems have been slow to adopt support for the Mongolian script, and almost all have incomplete support or other text rendering difficulties.

History

![The so-called Stone of Genghis Khan or Stele of Yisüngge, with the earliest known inscription in the Mongolian script.[1]: 33](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/46/Hermitage_hall_366_-_06.jpg/220px-Hermitage_hall_366_-_06.jpg)

The Mongolian vertical script developed as an adaptation of the Old Uyghur alphabet for the Mongolian language.[2]: 545 From the seventh and eighth to the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the Mongolian language separated into southern, eastern and western dialects. The principal documents from the period of the Middle Mongol language are: in the eastern dialect, the famous text The Secret History of the Mongols, monuments in the Square script, materials of the Chinese–Mongolian glossary of the fourteenth century, and materials of the Mongolian language of the middle period in Chinese transcription, etc.; in the western dialect, materials of the Arab–Mongolian and Persian–Mongolian dictionaries, Mongolian texts in Arabic transcription, etc.[3]: 1–2 The main features of the period are that the vowels ï and i had lost their phonemic significance, creating the i phoneme (in the Chakhar dialect, the Standard Mongolian in Inner Mongolia, these vowels are still distinct); inter-vocal consonants γ/g, b/w had disappeared and the preliminary process of the formation of Mongolian long vowels had begun; the initial h was preserved in many words; grammatical categories were partially absent, etc. The development over this period explains why the Mongolian script looks like a vertical Arabic script (in particular the presence of the dot system).[3]: 1–2

Eventually, minor concessions were made to the differences between the Uyghur and Mongol languages: In the 17th and 18th centuries, smoother and more angular versions of the letter tsadi became associated with [dʒ] and [tʃ] respectively, and in the 19th century, the Manchu hooked yodh was adopted for initial [j]. Zain was dropped as it was redundant for [s]. Various schools of orthography, some using diacritics, were developed to avoid ambiguity.[2]: 545

Traditional Mongolian is written vertically from top to bottom, flowing in lines from left to right. The Old Uyghur script and its descendants, of which traditional Mongolian is one among Oirat Clear, Manchu, and Buryat are the only known vertical scripts written from left to right. This developed because the Uyghurs rotated their Sogdian-derived script, originally written right to left, 90 degrees counterclockwise to emulate Chinese writing, but without changing the relative orientation of the letters.[4][1]: 36

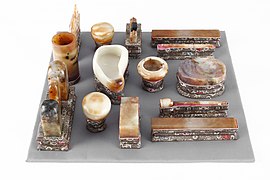

The reed pen was the writing instrument of choice until the 18th century, when the brush took its place under Chinese influence.[5]: 422 Pens were also historically made of wood, reed, bamboo, bone, bronze, or iron. Ink used was black or cinnabar red, and written with on birch bark, paper, cloths made of silk or cotton, and wooden or silver plates.[6]: 80–81

- Reed pens

- Ink brushes

- Writing implements of the Bogd Khan

Mongols learned their script as a syllabary, dividing the syllables into twelve different classes, based on the final phonemes of the syllables, all of which ended in vowels.[7]

The script remained in continuous use by Mongolian speakers in Inner Mongolia in the People's Republic of China. In the Mongolian People's Republic, it was largely replaced by the Mongolian Cyrillic alphabet, although the vertical script remained in limited use. In March 2020, the Mongolian government announced plans to increase the use of the traditional Mongolian script and to use both Cyrillic and Mongolian script in official documents by 2025.[8][9][10] However, due to the particularity of the traditional Mongolian script, a large part of the Sinicized Mongols in China can't identify the script, and in many cases the script is only used symbolically on plaques in many cities.[11][12]

Names

The script is known by a wide variety of names. As it was derived from the Old Uyghur alphabet, the Mongol script is known as the Uighur(-)Mongol script.[note 3] From 1941 onwards, it became known as the Old Script,[note 4] in contrast to the New Script,[note 5] referring to Cyrillic. The Mongolian script is also known as the Hudum or 'not exact' script,[note 6], in comparison with the Todo 'clear, exact' script [note 7].[13]: 308 [1]: 30–32, 38–39 [14]: 640 [15]: 7 [16][17]: 206 [18]

Overview

The traditional or classical Mongolian alphabet, sometimes called Hudum 'traditional' in Oirat in contrast to the Clear script (Todo 'exact'), is the original form of the Mongolian script used to write the Mongolian language. It does not distinguish several vowels (o/u, ö/ü, final a/e) and consonants (syllable-initial t/d and k/g, sometimes ǰ/y) that were not required for Uyghur, which was the source of the Mongol (or Uyghur-Mongol) script.[4] The result is somewhat comparable to the situation of English, which must represent ten or more vowels with only five letters and uses the digraph th for two distinct sounds. Ambiguity is sometimes prevented by context, as the requirements of vowel harmony and syllable sequence usually indicate the correct sound. Moreover, as there are few words with an exactly identical spelling, actual ambiguities are rare for a reader who knows the orthography.

Letters have different forms depending on their position in a word: initial, medial, or final. In some cases, additional graphic variants are selected for visual harmony with the subsequent character.

The rules for writing below apply specifically for the Mongolian language, unless stated otherwise.

Sort orders

- Traditional: n, q/k, γ/g, b, p, s, š, t, d, l, m, č...[19][20]: 7

- Modern: n, b, p, q/k, γ/g, m, l, s, š, t, d, č...[19][20]: 7

- Other modern orderings that apply to specific dictionaries also exist.[21]

Vowel harmony

Mongolian vowel harmony separates the vowels of words into three groups – two mutually exclusive and one neutral:

- The back, male, masculine,[22] hard, or yang[23] vowels a, o, and u.

- The front, female, feminine,[22] soft, or yin[23] vowels e, ö, and ü.

- The neutral vowel i, able to appear in all words.

Any Mongolian word can contain the neutral vowel i, but only vowels from either of the other two groups. The vowel qualities of visually separated vowels and suffixes must likewise harmonize with those of the preceding word stem. Such suffixes are written with front or neutral vowels when preceded by a word stem containing only neutral vowels. Any of these rules might not apply for foreign words however.[3]: 11, 35, 39 [24]: 10 [25]: 4 [21]

Separated final vowels

) and the final vowel ‑a (

) and the final vowel ‑a (  )

)A separated final form of vowels a or e is common, and can appear at the end of a word stem, or suffix. This form requires a final-shaped preceding letter, and an inter-word gap in between. This gap can be transliterated with a hyphen.[note 8][3]: 30, 77 [26]: 42 [1]: 38–39 [25]: 27 [27]: 534–535

The presence or lack of a separated a or e can also indicate differences in meaning between different words (compare ᠬᠠᠷᠠ⟨?⟩ qar‑a 'black' with ᠬᠠᠷᠠ qara 'to look').[28]: 3 [27]: 535

Its form could be confused with that of the identically shaped traditional dative-locative suffix ‑a/‑e exemplified further down. That form however, is more commonly found in older texts, and more commonly takes the forms of ⟨ᠲ᠋ᠤᠷ⟩ tur/tür or ⟨ᠳ᠋ᠤᠷ⟩ dur/dür instead.[24]: 15 [29][1]: 46

Separated suffixes

All case suffixes, as well as any plural suffixes consisting of one or two syllables, are likewise separated by a preceding and hyphen-transliterated gap.[note 9] A maximum of two case suffixes can be added to a stem.[3]: 30, 73 [24]: 12 [29][30][25]: 28 [27]: 534

Such single-letter vowel suffixes appear with the final-shaped forms of a/e, i, or u/ü,[3]: 30 as in ᠭᠠᠵᠠᠷ ᠠ⟨?⟩ γaǰar‑a 'to the country' and ᠡᠳᠦᠷ ᠡ⟨?⟩ edür‑e 'on the day',[3]: 39 or ᠤᠯᠤᠰ ᠢ⟨?⟩ ulus‑i 'the state' etc.[3]: 23 Multi-letter suffixes most often start with an initial- (consonants), medial- (vowels), or variant-shaped form. Medial-shaped u in the two-letter suffix ᠤᠨ⟨?⟩ ‑un/‑ün is exemplified in the adjacent newspaper logo.[3]: 30 [27]: 27

Consonant clusters

Two medial consonants are the most that can come together in original Mongolian words. There are however, a few loanwords that can begin or end with two or more.[note 10]

Compound names

In the modern language, proper names (but not words) usually forms graphic compounds (such as those of ᠬᠠᠰᠡᠷᠳᠡᠨᠢ Qas'erdeni 'Jasper-jewel' or ᠬᠥᠬᠡᠬᠣᠲᠠ Kökeqota – the city of Hohhot). These also allow components of different harmonic classes to be joined together, and where the vowels of an added suffix will harmonize with those of the latter part of the compound. Orthographic peculiarities are most often retained, as with the short and long teeth of an initial-shaped ö in ᠮᠤᠤᠥ᠌ᠬᠢᠨ Muu'ökin 'Bad Girl' (protective name). Medial t and d, in contrast, are not affected in this way.[3]: 30 [32]: 92 [1]: 44 [15]: 88

Isolate citation forms

Isolate citation forms for syllables containing o, u, ö, and ü may in dictionaries appear without a final tail as in ⟨ᠪᠣ⟩ bo/bu or ⟨ᠮᠣ᠋⟩ mo/mu, and with a vertical tail as in ⟨ᠪᠥ᠋⟩ bö/bü or ⟨ᠮᠥ᠋⟩ mö/mü (as well as in transcriptions of Chinese syllables).[21][1]: 39

Letters

Native Mongolian

| Letters [3]: 17, 18 [2]: 546 |

Contextual forms | Transliteration[note 11] | International Phonetic Alphabet | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Medial | Final | Latin | Cyrillic[34][33] | Khalkha[26]: 40–42 | Chakhar[21][35] | |

| ᠠ | ᠠ | ᠠ | ᠠ

ᠠ᠋ |

a | а | /a/ | /ɑ/ |

| ᠡ | ᠡ | ᠡ | ᠡ

ᠡ᠋ |

e | э | /ə/ | |

| ᠢ | ᠢ | ᠢ | ᠢ | i | и | /i/ | /i/ or /ɪ/ |

| ᠣ | ᠣ | ᠣ | ᠣ | o | о | /ɔ/ | |

| ᠤ | ᠤ | ᠤ | ᠤ | u | у | /ʊ/ | |

| ᠥ | ᠥ | ᠥ

ᠥ᠋ |

ᠥ | ö | ө | /ɵ/ | /o/ |

| ᠦ | ᠦ | ᠦ

ᠦ᠋ |

ᠦ | ü | ү | /u/ | |

| ᠨ | ᠨ | ᠨ

ᠨ᠋ |

ᠨ

ᠨ |

n | н | /n/ | |

| ᠩ | — | ᠩ | ᠩ | ng | нг | /ŋ/ | |

| ᠪ | ᠪ | ᠪ | ᠪ | b | б | /p/ and /w/ | /b/ |

| ᠫ | ᠫ | ᠫ | — | p | п | /pʰ/ | /p/ |

| ᠬ | ᠬ

|

ᠬ

|

ᠬ | q

k |

х | /x/ | |

| ᠭ | ᠭ

|

ᠭ

ᠭ᠋

|

ᠭ

ᠭ

|

γ

g |

г | /ɢ/ | /ɣ/ |

| ᠮ | ᠮ | ᠮ | ᠮ | m | м | /m/ | |

| ᠯ | ᠯ | ᠯ | ᠯ | l | л | /ɮ/ | /l/ |

| ᠰ | ᠰ | ᠰ | ᠰ | s | с | /s/ or /ʃ/ before i | |

| ᠱ | ᠱ | ᠱ | ᠱ | š | ш | /ʃ/ | |

| ᠲ | ᠲ | ᠲ | — | t | т | /t/ | |

| ᠳ | ᠳ | ᠳ

ᠳ᠋ |

ᠳ | d | д | /t/ and /tʰ/ | /d/ |

| ᠴ | ᠴ | ᠴ | — | č | ч | /t͡ʃʰ/ and /t͡sʰ/ | /t͡ʃ/ |

| ᠵ | ᠵ | ᠵ | — | ǰ | ж | /d͡ʒ/ and d͡z | /d͡ʒ/ |

| ᠶ | ᠶ | ᠶ | ᠶ | y | й | /j/ | |

| ᠷ | ᠷ | ᠷ | ᠷ | r | р | /r/ | |

Galik characters

In 1587, the translator and scholar Ayuush Güüsh (Аюуш гүүш) created the Galik alphabet (Али-гали Ali-gali), inspired by the third Dalai Lama, Sonam Gyatso. It primarily added extra characters for transcribing Tibetan and Sanskrit terms when translating religious texts, and later also from Chinese. Some of those characters are still in use today for writing foreign names (as listed below).[36]

| Letters [3]: 17, 18 [2]: 546 |

Contextual forms | Transliteration[note 11] | IPA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Medial | Final | Latin | Cyrillic[34][33] | Sanskrit | Tibetan[3]: 28 [37]: 86, 244, 251 | ||

| ᠧ | ᠧ | ᠧ | ᠧ | ē | е | /e/ | ||

| ᠸ | ᠸ | ᠸ | ᠸ | w | в | ཝ | /w/ | |

| ᠹ | ᠹ | ᠹ | ᠹ | f | ф | ཕ | /f/ | |

| ᠺ | ᠺ | ᠺ | ᠺ | g | к | ग | ག | /k/ |

| ᠻ | ᠻ | ᠻ | ᠻ | kh | к | ख | ཁ | /kʰ/ |

| ᠼ | ᠼ | ᠼ | ᠼ | c | ц | छ | ཚ | /t͡s/ |

| ᠽ | ᠽ | ᠽ | ᠽ | z | з | ज | ཛ | /d͡z/ |

| ᠾ | ᠾ | ᠾ | ᠾ | h | х | ह | ཧ | /h/ |

| ᠿ | ᠿ | ᠿ | ᠿ | ž[lower-alpha 1] | ж | ཞ | /ʐ/, /ɻ/[lower-alpha 2] | |

| ᡀ | ᡀ | ᡀ | ᡀ | lh | лх | ལྷ | /ɬ/ | |

| ᡁ | ᡁ | ᡁ | ᡁ | zh[lower-alpha 3] | з | /d͡ʐ/ | ||

| ᡂ | ᡂ | ᡂ | ᡂ | ch[lower-alpha 4] | ч | /t͡ʂ/ | ||

- used in Inner Mongolia.

- Transcribes Chinese r /ɻ/ [ɻ ~ ʐ]; Lee & Zee (2003) and Lin (2007) transcribe these as approximants, while Duanmu (2007) transcribes these as voiced fricatives. The actual pronunciation has been acoustically measured to be more approximant-like as in 日 Ri, and used in Inner Mongolia. Always followed by an i.[35][38]

- used in Inner Mongolia.

- as in 蚩 Chī, used in Inner Mongolia.

Punctuation and numerals

Punctuation

When written between words, punctuation marks use space on both sides of them. They can also appear at the very end of a line, regardless of where the preceding word ends.[32]: 99 Red (cinnabar) ink is used in many manuscripts, to either symbolize emphasis or respect.[32]: 241 Modern punctuation incorporates Western marks: parentheses; quotation, question, and exclamation marks; including precomposed ⁈ and ⁉.[27]: 535–536

| Form(s) | Name | Function(s) |

|---|---|---|

| ᠀ | Birga[note 12] | Marks start of a book, chapter, passage, or first line |

| ᠀᠋ | ||

| ᠀᠌ | ||

| ᠀᠍ | ||

| [...] | ||

| ᠂ | 'Dot'[note 13] | Comma |

| ᠃ | 'Double-dot'[note 14] | Period / full stop |

| ᠅ | 'Four-fold dot'[note 15] | Marks end of a passage, paragraph, or chapter |

| ᠁ | 'Dotted line'[note 16] | Ellipsis |

| ᠄ | [...][note 17] | Colon |

| ᠆ | 'Spine, backbone'[note 18] | Mongolian soft hyphen (wikt:᠆) |

| ᠊ | Mongolian non-breaking hyphen, or stem extender (wikt:᠊) |

Numerals

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ᠐ | ᠑ | ᠒ | ᠓ | ᠔ | ᠕ | ᠖ | ᠗ | ᠘ | ᠙ |

Mongolian numerals are either written from left to right, or from top to bottom.[3]: 54 [34]: 9

| ᠑᠕ ᠣᠨ 15 on 'year of 15' on a 1925 tögrög coin[40] | |

| The number ᠘᠙ 89 written vertically on a hillside (top) |

Components and writing styles

Components

Listed in the table below are letter components (graphemes)[note 19] commonly used across the script. Some of these are used with several letters, and others to contrast between them. As their forms and usage may differ between writing styles, however, examples of these can be found under this section below.

| Form | Name(s) | Used with |

|---|---|---|

| ᠡ | 'Crown'[note 20] | all initial vowels (a, e, i, o, u, ö, ü, ē), and some initial consonants (n, m, l, h, etc). |

| ᠊ᠡ | 'Tooth'[note 21] |

|

| 'Tooth'[note 22] | ||

| ᠊᠊ | 'Spine, backbone'[note 23] | the vertical line running through words. |

| ᠊ᠠ | 'Tail'[note 24] | a, e, n, d, etc. A final connected flourish/swash pointing right. |

| ᠊ᠰ᠋ | 'Short tail'[note 25] | final q, γ, m, and s |

| ᠠ⟨?⟩ ⟨ |

[...][note 26] | separated final a/e. |

| 'Sprinkling, dusting'[note 27] | lower part of final a/e; the lower part of final g. | |

| ᡳ᠌ | 'Hook'[note 28] | lower part of final i and d. |

| ᠵ | 'Shin, stick'[note 29] | i; initial ö and ü; the upper part of final g; ǰ and y, etc. |

| 'Straight shin'[note 30] | ||

| 'Long tooth'[note 31] | ||

| ᠶ | 'Shin with upturn'[note 32] | y. |

| ᠸ | Shin with downturn[note 33] | ē and w. |

| ᠷ | Horned shin[note 34] |

|

| ᠳ᠋ | 'Looped shin'[note 35] | t and d. |

| ᡁ | 'Hollow shin'[note 36] | h and zh. |

| ᠢ | 'Bow'[note 37] | final i, o–ü, and r; ng, b, p, k, g, etc. |

| ᠊ᠣ | 'Belly, stomach,' loop, contour[note 38] | the enclosed part of o–ü, b, p, initial t and d, etc. |

| ᠲ | 'Hind-gut'[note 39] | initial t and d. |

| ᠊ᠹ | Flaglet, tuft[note 40] | the left-side diacritic of f and z. |

| ᠽ | ||

| ᠬ | [...][note 41] | initial q and γ. |

| ᠊ᠮ | 'Braid, pigtail'[note 42] | m. |

| 'Horn'[note 43] | ||

| ᠊ᠯ | 'Horn'[note 44] | l. |

| 'Braid, pigtail'[note 45] | ||

| ᠊ᠰ | 'Corner of the mouth'[note 46] | s and š. |

| ᠴ | [...][note 47] | č. |

| 'Fork'[note 48] | ||

| ᠵ | [...][note 49] | ǰ. |

| 'Tusk, fang'[note 50] |

Writing styles

As exemplified in this section, the shapes of glyphs may vary widely between different styles of writing and choice of medium with which to produce them. The development of written Mongolian can be divided into the three periods of pre-classical (beginning – 17th century), classical (16/17th century – 20th century), and modern (20th century onward):[31][3]: 2–3, 17, 23, 25–26 [24]: 58–59 [2]: 539–540, 545–546 [34]: 62–63 [48]: 111, 113–114 [26]: 40–42, 100–101, 117 [1]: 34–37 [49]: 8–11 [17]: 211–215

- Rounded letterforms tend to be more prevalent with handwritten styles (compare printed and handwritten arban 'ten').

| Block‑printed | Pen-written form | Modern brush‑ |

Transliteration(s) & 'translation' | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uyghur Mong. form | semi-modern forms | |||

| arban 'ten' | ||||

- Final letterforms with a right-pointing tail (such as those of a, e, n, q, γ, m, l, s, š, and d) may have the notch preceding it in printed form, written in a span between two extremes: from as a more or less tapered point, to a fully rounded curve in handwriting.

- The long final tails of a, e, n, and d in the texts of pre-classical Mongolian can become elongated vertically to fill up the remainder of a line. Such tails are used consistently for these letters in the earliest 13th to 15th century Uyghur Mongolian style of texts.

| Block‑printed | Pen-written forms | Modern brush‑ |

Transliteration(s) & 'translation' | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uyghur Mong. forms | semi-modern forms | |||

| ‑ača/ | ||||

| ‑un/ | ||||

| ‑ud/ | ||||

| ba 'and' | ||||

- A hooked form of yodh was borrowed from the Manchu alphabet in the 19th century to distinguish initial y from ǰ. The handwritten form of final-shaped yodh (i, ǰ, y), can be greatly shortened in comparison with its initial and medial forms.

| Block‑printed | Pen-written forms | Modern brush‑ |

Transliteration(s) & 'translation' | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uyghur Mong. forms | semi-modern forms | |||

| ‑i | ||||

| ‑yi | ||||

| ‑yin | ||||

| sain/sayin 'good' | ||||

| yeke 'great' | ||||

- The definite status or function of diacritics was not established prior to classical Mongolian. As such, the dotted letters n, γ, and š, can be found sporadically dotted or altogether lacking them. Additionally, both q and γ could be (double-)dotted to identify them regardless of their sound values. Final dotted n is also found in modern Mongolian words. Any diacritical dots of γ and n can be offset downward from their respective letters (as in ᠭᠣᠣᠯ

γool and ᠭᠦᠨ ᠢ⟨?⟩

γool and ᠭᠦᠨ ᠢ⟨?⟩  gün‑i).

gün‑i). - When a bow-shaped consonant is followed by a vowel in Uyghur style text, said bow can be found to notably overlap it (see bi). A final b has, in its final pre-modern form, a bow-less final form as opposed to the common modern one:[1]: 39

| Block‑printed | Pen-written forms | Modern brush‑ |

Transliteration(s) & 'translation' | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uyghur Mong. forms | semi-modern forms | |||

| ‑u/ | ||||

| bi 'I' | ||||

| ab (intensifying particle) | ||||

- As in

/

/ kü, köke, ǰüg and separated a/e, two teeth can also make up the top-left part of a kaph (k/g) or aleph (a/e) in pre-classical texts. In back-vocalic words of Uyghur Mongolian, qi was used in place of ki, and can therefore be used to identify this stage of the written language. An example of this appears in the suffix

kü, köke, ǰüg and separated a/e, two teeth can also make up the top-left part of a kaph (k/g) or aleph (a/e) in pre-classical texts. In back-vocalic words of Uyghur Mongolian, qi was used in place of ki, and can therefore be used to identify this stage of the written language. An example of this appears in the suffix  ‑taqi/‑daqi.[26]: 100, 117

‑taqi/‑daqi.[26]: 100, 117

| Block‑printed | Pen-written forms | Modern brush‑ |

Transliteration(s) & 'translation' | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uyghur Mong. forms | semi-modern forms | |||

| ‑a/ | ||||

| ‑luγ‑a | ||||

| köke 'blue' | ||||

| köge 'soot' | ||||

| ǰüg 'direction' | ||||

- In pre-modern Mongolian, medial ml (ᠮᠯ) forms a ligature:

.

. - A pre-modern variant form for final s appears in the shape of a short final n ⟨ᠰ᠋⟩, derived from Old Uyghur zayin (𐽴). It tended to be replaced by the mouth-shaped form and is no longer used. An early example of it is found in the name of Gengis Khan on the Stele of Yisüngge: ᠴᠢᠩᠭᠢᠰ᠋ Činggis. A zayin-shaped final can also appear as part of final m and γ.

| Block‑printed | Pen-written forms | Transliteration(s) & 'translation' | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uyghur Mong. forms | semi-modern forms | ||

| es(‑)e 'not, no', (negation) | |||

| ulus 'nation' | |||

| nom 'book' | |||

| čaγ 'time' | |||

- Initial taw (t/d) can, akin to final mem (m), be found written quite explicitly loopy (as in nom 'book' and toli 'mirror'). The lamedh (t or d) may appear simply as an oval loop or looped shin, or as more angular, with an either closed or open counter (as in ‑daki/‑deki or ‑dur/‑dür). As in metü, a Uyghur style word-medial t can sometimes be written with the pre-consonantal form otherwise used for d. Taw was applied to both initial t and d from the outset of the script's adoption. This was done in imitation of Old Uyghur which, however, had lacked the phoneme d in this position.

| Block‑printed | Pen-written forms | Modern brush‑ |

Transliteration(s) & 'translation' | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uyghur Mong. forms | semi-modern forms | |||

| [...] | toli 'mirror' | |||

| [...] | ‑daki/‑deki | |||

| [...] | ‑tur/ | |||

| ‑dur/ | ||||

| [...] | metü 'as' | |||

![The word čiγšabd in a Uyghur Mongolian style: exemplifying a dotted syllable-final γ, and a final bd ligature.[citation needed]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ac/Block-printed_%C4%8Di%CE%B3%C5%A1abd_2.svg/84px-Block-printed_%C4%8Di%CE%B3%C5%A1abd_2.svg.png)

- Following the late classical Mongolian orthography of the 17th and 18th centuries, a smooth and angular tsade (ᠵ and ᠴ) has come to represent ǰ and č respectively. The tsade before this was used for both these phonemes, regardless of graphical variants, as no ǰ had existed in Old Uyghur:

| Block‑printed | Transliteration(s) & 'translation' | |

|---|---|---|

| Uyghur Mong. form | semi-modern form | |

| čečeg 'flower' | ||

| Block-printed semi-modern form | Pen-written form | Transliteration(s) & 'translation' |

|---|---|---|

| qačar/γaǰar 'cheek/place' |

- As in sara and ‑dur/‑dür, a resh (of r, and sometimes of l) can appear as two teeth or crossed shins; adjacent, angled, attached to a shin and/or overlapping.

| Block‑printed | Pen-written form | Modern brush‑ |

Transliteration(s) & 'translation' | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uyghur Mong. form | semi-modern forms | |||

| sar(‑)a 'moon/month' | ||||

Example

| Manuscript | Type | Unicode | Transliteration (first word) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

ᠸᠢᠺᠢᠫᠧᠳᠢᠶᠠ᠂ ᠴᠢᠯᠦᠭᠡᠲᠦ ᠨᠡᠪᠲᠡᠷᠬᠡᠢ ᠲᠣᠯᠢ ᠪᠢᠴᠢᠭ ᠪᠣᠯᠠᠢ᠃ |

ᠸᠢ wi/ |

| ᠺᠢ gi/ki | |||

| ᠫᠧ pē/pé | |||

| ᠳᠢ di | |||

| ᠶᠠ ya | |||

| |||

Gallery

![Folded script style on the coat of arms of Govisümber Province[5]: 427](//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d8/Mn_coa_govis%C3%BCmber_aimag.svg/72px-Mn_coa_govis%C3%BCmber_aimag.svg.png) Folded script style on the coat of arms of Govisümber Province[5]: 427

Folded script style on the coat of arms of Govisümber Province[5]: 427- Mongolian calligraphy of the 13th century work Оюун Түлхүүр (Key of Intelligence)

- ''Mandukhai setsen khatan'' (film) title screen, 1988

Stele for Queen Mandukhai the Wise

Stele for Queen Mandukhai the Wise- Cover page with printed hand-lettering in red, early 20th century

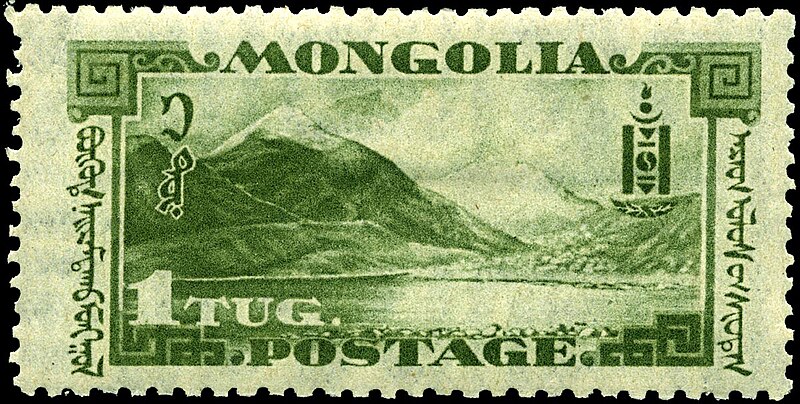

- Postage stamp with words augmented with letters from the Manchu alphabet, 1932

- 1 Mongolian tögrög, 1925

- Mongolian dollar with a long body of printed text, 1921

- Imperial seal of the Bogd Khan, ca 1911.

- Mixed Manchu–Mongolian text on a Paiza.

- Poem composed and brush-written by Injinash, 19th century

Mongolian Diamond Sutra manuscript, 19th century

Mongolian Diamond Sutra manuscript, 19th century- Nogeoldae textbook in Korean and Mongolian, 18th century

- Mongolian on the far left of a Yonghe Temple board in Beijing, 1722

- Letter from the Il-Khan Öljaitü to King Philip IV of France, 1305

- Silver dirham from the reign of the Il-Khan Arghun, 1297

- Imperial seal of Güyük Khan in letter to Pope Innocent IV, 1246

Unicode

The Mongolian script was added to the Unicode standard in September 1999 with the release of version 3.0. However, several design issues have been pointed out.[50]

- The 1999 Mongolian script Unicode codes are duplicated and not searchable.

- The 1999 Mongolian script Unicode model has multiple layers of FVS (free variation selectors), MVS, ZWJ, NNBSP, and those variation selections conflict with each other, which create incorrect results.[51] Furthermore, different vendors understood the definition of each FVS differently, and developed multiple applications in different standards.[52]

Blocks

The Unicode block for Mongolian is U+1800–U+18AF. It includes letters, digits and various punctuation marks for Hudum Mongolian, Todo Mongolian, Xibe (Manchu), Manchu proper, and Ali Gali, as well as extensions for transcribing Sanskrit and Tibetan.

| Mongolian[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+180x | ᠀ | ᠁ | ᠂ | ᠃ | ᠄ | ᠅ | ᠆ | ᠇ | ᠈ | ᠉ | ᠊ | FVS 1 |

FVS 2 |

FVS 3 |

MVS | FVS 4 |

| U+181x | ᠐ | ᠑ | ᠒ | ᠓ | ᠔ | ᠕ | ᠖ | ᠗ | ᠘ | ᠙ | ||||||

| U+182x | ᠠ | ᠡ | ᠢ | ᠣ | ᠤ | ᠥ | ᠦ | ᠧ | ᠨ | ᠩ | ᠪ | ᠫ | ᠬ | ᠭ | ᠮ | ᠯ |

| U+183x | ᠰ | ᠱ | ᠲ | ᠳ | ᠴ | ᠵ | ᠶ | ᠷ | ᠸ | ᠹ | ᠺ | ᠻ | ᠼ | ᠽ | ᠾ | ᠿ |

| U+184x | ᡀ | ᡁ | ᡂ | ᡃ | ᡄ | ᡅ | ᡆ | ᡇ | ᡈ | ᡉ | ᡊ | ᡋ | ᡌ | ᡍ | ᡎ | ᡏ |

| U+185x | ᡐ | ᡑ | ᡒ | ᡓ | ᡔ | ᡕ | ᡖ | ᡗ | ᡘ | ᡙ | ᡚ | ᡛ | ᡜ | ᡝ | ᡞ | ᡟ |

| U+186x | ᡠ | ᡡ | ᡢ | ᡣ | ᡤ | ᡥ | ᡦ | ᡧ | ᡨ | ᡩ | ᡪ | ᡫ | ᡬ | ᡭ | ᡮ | ᡯ |

| U+187x | ᡰ | ᡱ | ᡲ | ᡳ | ᡴ | ᡵ | ᡶ | ᡷ | ᡸ | |||||||

| U+188x | ᢀ | ᢁ | ᢂ | ᢃ | ᢄ | ᢅ | ᢆ | ᢇ | ᢈ | ᢉ | ᢊ | ᢋ | ᢌ | ᢍ | ᢎ | ᢏ |

| U+189x | ᢐ | ᢑ | ᢒ | ᢓ | ᢔ | ᢕ | ᢖ | ᢗ | ᢘ | ᢙ | ᢚ | ᢛ | ᢜ | ᢝ | ᢞ | ᢟ |

| U+18Ax | ᢠ | ᢡ | ᢢ | ᢣ | ᢤ | ᢥ | ᢦ | ᢧ | ᢨ | ᢩ | ᢪ | |||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

The Mongolian Supplement block (U+11660–U+1167F) was added to the Unicode Standard in June 2016 with the release of version 9.0:

| Mongolian Supplement[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1166x | 𑙠 | 𑙡 | 𑙢 | 𑙣 | 𑙤 | 𑙥 | 𑙦 | 𑙧 | 𑙨 | 𑙩 | 𑙪 | 𑙫 | 𑙬 | |||

| U+1167x | ||||||||||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

See also

- Mongolian writing systems

- Mongolian script

- ʼPhags-pa script

- Horizontal square script

- Soyombo script

- Mongolian Latin alphabet

- SASM/GNC romanization § Mongolian

- Mongolian Cyrillic alphabet

- Mongolian transliteration of Chinese characters

- Sino–Mongolian Transliterations

- Mongolian Braille

- Mongolian Sign Language

- Mongolian name

Notes

- In Mongolian script: ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠣᠯ ᠪᠢᠴᠢᠭ ⟨

⟩ Mongol bichig; in Mongolian Cyrillic: Монгол бичиг Mongol bichig

⟩ Mongol bichig; in Mongolian Cyrillic: Монгол бичиг Mongol bichig - In Mongolian script: ᠬᠤᠳᠤᠮ ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠣᠯ ᠪᠢᠴᠢᠭ; Khalkha: Худам Монгол бичиг; Buryat: Худам Монгол бэшэг, Kudam Mongol besheg; Kalmyk: Хуудм Моңһл бичг, Xuudm Moñğl biçg[citation needed]

- ᠤᠶᠢᠭᠤᠷᠵᠢᠨ ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠣᠯ ᠪᠢᠴᠢᠭ uyiγurǰin mongγol bičig (уйгар/уйгаржин/уйгуржин монгол бичиг/үсэг uigar/uigarjin/uigurjin mongol bichig/üseg)

- ᠬᠠᠭᠤᠴᠢᠨ ᠪᠢᠴᠢᠭ qaγučin bičig (хуучин бичиг khuuchin bichig)

- ᠰᠢᠨᠡ/ᠰᠢᠨᠡ ᠪᠢᠴᠢᠭ sine/sin‑e bičig (шинэ үсэг shine üseg)

- ᠬᠤᠳᠤᠮ ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠣᠯ ᠪᠢᠴᠢᠭ qudum mongγol bičig (худам монгол бичиг khudam mongol bichig)

- ᠲᠣᠳᠣ ᠪᠢᠴᠢᠭ/ᠦᠰᠦᠭ todo bičig/üsüg (тод бичиг/үсэг tod bichig/üseg)

- In digital typesetting, this shaping is achieved by inserting a U+180E MONGOLIAN VOWEL SEPARATOR (

MVS) between the separated letters. - In digital typesetting, this shaping is achieved by inserting a U+202F NARROW NO-BREAK SPACE (

NNBSP) between the separated letters. - Examples of such include: (dotless š) gšan 'moment' (

), gkir 'dirt' (

), gkir 'dirt' ( ), or bodisdv 'Bodhisattva' (

), or bodisdv 'Bodhisattva' ( ).[3]: 15, 32 [24]: 9 [31]: 385

).[3]: 15, 32 [24]: 9 [31]: 385 - Scholarly/Scientific transliteration.[33]

- ᠪᠢᠷᠭᠠ⟨?⟩ birγ‑a (бярга byarga)

- ᠴᠡᠭ čeg (цэг tseg)

- ᠳᠠᠪᠬᠤᠷ ᠴᠡᠭ dabqur čeg (давхар цэг davkhar tseg)

- ᠳᠥᠷᠪᠡᠯᠵᠢᠨ ᠴᠡᠭ dörbelǰin čeg (дөрвөлжин цэг dörvöljin tseg)

- ᠴᠤᠪᠠᠭᠠ/ᠴᠤᠪᠤᠭᠠ⟨?⟩ ᠴᠡᠭ čubaγ‑a/čubuγ‑a čeg (цуваа цэг tsuvaa tseg)

- ᠬᠣᠣᠰ ᠴᠡᠭ qoos čeg (хос цэг khos tseg)[citation needed]

- ᠨᠢᠷᠤᠭᠤ niruγu (нуруу nuruu)

- Mongolian: ᠵᠢᠷᠤᠯᠭᠠ ǰirulγ‑a / зурлага zurlaga

- ᠲᠢᠲᠢᠮ titim (тит(и/э)м tit(i/e)m)

- ᠠᠴᠤᠭ ačuγ (ацаг atsag)

- ᠰᠢᠳᠦ sidü (шүд shüd)

- ᠨᠢᠷᠤᠭᠤ niruγu (нуруу nuruu)

- ᠰᠡᠭᠦᠯ segül (сүүл süül)

- ᠪᠣᠭᠤᠨᠢ ᠰᠡᠭᠦᠯ boγuni segül (богино/богонь сүүл bogino/bogoni süül)

- ᠣᠷᠬᠢᠴᠠ orkiča (орхиц orkhits)

- ᠴᠠᠴᠤᠯᠭᠠ⟨?⟩ čačulγ‑a (цацлага tsatslaga)

- ᠳᠡᠭᠡᠭᠡ degege (дэгээ degee)

- ᠰᠢᠯᠪᠢ silbi (шилбэ shilbe)

- ᠰᠢᠯᠤᠭᠤᠨ ᠰᠢᠯᠪᠢ siluγun silbi (шулуун шилбэ shuluun shilbe)

- ᠤᠷᠲᠤ ᠰᠢᠳᠦ urtu sidü (урт шүд urt shüd)

- ᠡᠭᠡᠲᠡᠭᠡᠷ ᠰᠢᠯᠪᠢ egeteger silbi (э(э)тгэр шилбэ e(e)tger shilbe)

- ᠮᠠᠲᠠᠭᠠᠷ ᠰᠢᠯᠪᠢ mataγar silbi (матгар шилбэ matgar shilbe)

- ᠥᠷᠭᠡᠰᠦᠲᠡᠢ ᠰᠢᠯᠪᠢ örgesütei silbi (өргөстэй шилбэ örgöstei shilbe)

- ᠭᠣᠭᠴᠤᠭᠠᠲᠠᠢ ᠰᠢᠯᠪᠢ γoγčuγatai silbi (гогцоотой шилбэ gogtsootoi shilbe)

- ᠬᠥᠨᠳᠡᠢ ᠰᠢᠯᠪᠢ köndei silbi (хөндий шилбэ khöndii shilbe)

- ᠨᠤᠮᠤ numu (нум num)

- ᠭᠡᠳᠡᠰᠦ gedesü (гэдэс gedes)

- ᠠᠷᠤ ᠶᠢᠨ ᠭᠡᠳᠡᠰᠦ⟨?⟩ aru‑yin gedesü (арын гэдэс aryn gedes)

- ᠵᠠᠷᠲᠢᠭ ǰartiγ (зартиг zartig Wylie: 'jar-thig)

- [...] (ятгар зартиг yatgar zartig)

- ᠭᠡᠵᠢᠭᠡ geǰige (гэзэг gezeg)

- ᠡᠪᠡᠷ eber (эвэр ever)

- ᠡᠪᠡᠷ eber (эвэр ever)

- ᠭᠡᠵᠢᠭᠡ geǰige (гэзэг gezeg)

- ᠵᠠᠪᠠᠵᠢ ǰabaǰi (зав(и/ь)ж zavij)

- ᠰᠡᠷᠡᠭᠡ ᠡᠪᠡᠷ serege eber (сэрээ эвэр seree ever)

- ᠠᠴᠠ ača (ац ats)

- [...] (жалжгар эвэр jaljgar ever)

- ᠰᠣᠶᠤᠭᠠ⟨?⟩ soyuγ‑a (соёо soyoo)

References

- Janhunen, Juha (2006-01-27). The Mongolic Languages. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-79690-7.

- Daniels, Peter T. (1996). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507993-7.

- Poppe, Nicholas (1974). Grammar of Written Mongolian. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-00684-2.

- György Kara, "Aramaic Scripts for Altaic Languages", in Daniels & Bright The World's Writing Systems, 1994.

- Shepherd, Margaret (2013-07-03). Learn World Calligraphy: Discover African, Arabic, Chinese, Ethiopic, Greek, Hebrew, Indian, Japanese, Korean, Mongolian, Russian, Thai, Tibetan Calligraphy, and Beyond. Potter/Ten Speed/Harmony/Rodale. ISBN 978-0-8230-8230-8.

- Berkwitz, Stephen C.; Schober, Juliane; Brown, Claudia (2009-01-13). Buddhist Manuscript Cultures: Knowledge, Ritual, and Art. Routledge. ISBN 9781134002429.

- Chinggeltei. (1963) A Grammar of the Mongol Language. New York, Frederick Ungar Publishing Co. p. 15.

- "Mongolia to promote usage of traditional script". China.org.cn (March 19, 2020).

- Official documents to be recorded in both scripts from 2025, Montsame, 18 March 2020.

- Mongolian Language Law is effective from July 1st, Gogo, 1 July 2015. "Misinterpretation 1: Use of cyrillic is to be terminated and only Mongolian script to be used. There is no provision in the law that states the termination of use of cyrillic. It clearly states that Mongolian script is to be added to the current use of cyrillic. Mongolian script will be introduced in stages and state and local government is to conduct their correspondence in both cyrillic and Mongolian script. This provision is to be effective starting January 1st of 2025. ID, birth certificate, marriage certificate and education certificates are to be both in Mongolian cyrillic and Mongolian script and currently Mongolian script is being used in official letters of President, Prime Minister and Speaker of Parliament."

- Caodaobateer (2004). "The Use and Development of Mongol and its Writing Systems in China". Language Policy in the People's Republic of China. Language Policy. 4: 289–302. doi:10.1007/1-4020-8039-5_16. ISBN 1-4020-8038-7.

- Hsiao-ting Lin. "Ethnopolitics in modern China: the Nationalists, Muslims, and Mongols in wartime Alashaa Banner (1937–1945)". Stanford, CA, USA: Hoover Institution, Stanford University.

- Publishing, International Conference on Electronic (1998-03-18). EP '98. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-540-64298-5.

- Sanders, Alan J. K. (2010-05-20). Historical Dictionary of Mongolia. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7452-7.

- Janhunen, Juha A. (2012). Mongolian. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-9027238207.

- Bawden, Charles (2013-10-28). Mongolian English Dictionary. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-15595-6.

- Bat-Ireedui, Jantsangiyn; Sanders, Alan J. K. (2015-08-14). Colloquial Mongolian: The Complete Course for Beginners. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-30598-9.

- "Mongolian State Dictionary". mongoltoli.mn (in Mongolian). Retrieved 2017-12-14.

- "Unicode Technical Report #2". ftp.tc.edu.tw. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- Jugder, Luvsandorj (2008). "Diacritic marks in the Mongolian script and the 'darkness of confusion of letters'". In J. Vacek; A. Oberfalzerová (eds.). MONGOLO-TIBETICA PRAGENSIA '08, Linguistics, Ethnolinguistics, Religion and Culture. Mongolo-Tibetica Pragensia: Ethnolinguistics, Sociolinguistics, Religion and Culture. Vol. 1/1. Praha: Charles University and Triton. pp. 45–98. ISSN 1803-5647.

- "Mongolian Traditional Script". cjvlang.com. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- by Manchu convention

- in Inner Mongolia.

- Grønbech, Kaare; Krueger, John Richard (1993). An Introduction to Classical (literary) Mongolian: Introduction, Grammar, Reader, Glossary. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-03298-8.

- "A Study of Traditional Mongolian Script Encodings and Rendering: Use of Unicode in OpenType fonts" (PDF). w.colips.org. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- Svantesson, Jan-Olof (2005). The Phonology of Mongolian. Oxford University Press. pp. 40–42. ISBN 0-19-926017-6.

- "The Unicode® Standard Version 10.0 – Core Specification: South and Central Asia-II" (PDF). Unicode.org. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- "Mongolian / ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠣᠯ Moŋġol" (PDF). www.eki.ee. Retrieved 2017-11-18.

- Viklund, Andreas. "Lingua Mongolia – Mongolian Grammar". www.linguamongolia.com. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- "PROPOSAL Encode Mongolian Suffix Connector (U+180F) To Replace Narrow Non-Breaking Space (U+202F)" (PDF). Unicode.org. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- Lessing, Ferdinand (1960). Mongolian-English Dictionary (PDF). University of California Press. Note that this dictionary uses the transliterations c, ø, x, y, z, ai, and ei; instead of č, ö, q, ü, ǰ, ayi, and eyi;: xii as well as problematically and incorrectly treats all rounded vowels (o/u/ö/ü) after the initial syllable as u or ü.[41]

- Kara, György (2005). Books of the Mongolian Nomads: More Than Eight Centuries of Writing Mongolian. Indiana University, Research Institute for Inner Asian Studies. ISBN 978-0-933070-52-3.

- "Mongolian transliterations" (PDF). Institute of the Estonian Language]].

- Скородумова, Лидия Григорьевна (2000). Введение в старописьменный монгольский язык: учебное пособие (PDF) (in Russian). Изд-во Дом "Муравей-Гайд". ISBN 9785846300156.

- "Writing | Study Mongolian". www.studymongolian.net. Retrieved 2017-12-14.

- Otgonbayar Chuluunbaatar (2008). Einführung in die Mongolischen Schriften (in German). Buske. ISBN 978-3-87548-500-4.

- "BabelStone: Mongolian and Manchu Resources". babelstone.co.uk (in Chinese). Retrieved 2021-02-22.

- Lee-Kim, Sang-Im (2014), "Revisiting Mandarin 'apical vowels': An articulatory and acoustic study", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 44 (3): 261–282, doi:10.1017/s0025100314000267, S2CID 16432272

- Shagdarsürüng, Tseveliin (2001). "Study of Mongolian Scripts (Graphic Study or Grammatology). Enl". Bibliotheca Mongolica: Monograph 1.

- "Coins". Bank of Mongolia. 2006-03-09. Archived from the original on 2006-03-09. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- "University of Virginia: Mongolian Transliteration & Transcription". collab.its.virginia.edu. Retrieved 2021-02-22.

- Sanders, Alan (2003-04-09). Historical Dictionary of Mongolia. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6601-0.

- "The Mongolian Script" (PDF). Lingua Mongolia.

- Mongol Times (2012). "Monggul bichig un job bichihu jui-yin toli" (in Mongolian).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)[clarification needed] - "Analysis of the graphetic model and improvements to the current model" (PDF). www.unicode.org. Retrieved 2020-08-13.

- Gehrke, Munkho. "Монгол бичгийн зурлага :|: Монгол бичиг". mongol-bichig.dusal.net (in Mongolian). Retrieved 2019-04-18.

- "ᠵᠢᠷᠤᠯᠭᠠ ᠪᠠ ᠲᠡᠭᠦᠨ ᠦ ᠨᠡᠷᠡᠢᠳᠦᠯ - ᠮᠤᠩᠭᠤᠯ ᠪᠢᠴᠢᠭ". www.mongolfont.com (in Mongolian). Retrieved 2019-04-18.

- Clauson, Gerard (2005-11-04). Studies in Turkic and Mongolic Linguistics. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-43012-3.

- "Exploring Mongolian Manuscript Collections in Russia and Beyond" (PDF). www.manuscript-cultures.uni-hamburg.de. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- Liang, Hai (23 Sep 2017). "Current problems in the Mongolian encoding" (PDF). Unicode. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 June 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- Anderson, Debbie (22 Sep 2018). "Mongolian Ad Hoc meeting summary" (PDF). Unicode.

- Moore, Lisa (27 Mar 2019). "Summary of MWG2 Outcomes and Goals for MWG3 Meeting" (PDF). Unicode.Org.

External links

- Summaries

- University of Vienna: Grammar of Written Mongolian by Nicholas POPPE Index

- CJVlang: Making Sense of the Traditional Mongolian Script

- StudyMongolian: Written forms with audio pronunciation

- The Silver Horde: Mongol Scripts

- Lingua Mongolia: Uighur-script Mongolian Resources

- Omniglot: Mongolian Alphabet (note: contains several table inaccuracies regarding glyphs and transliterations)

- Dictionaries

- Transliteration

- University of Virginia: Transliteration Schemes For Mongolian Vertical Script

- Online tool for Mongolian script transliteration

- Automatic converter for Traditional Mongolian and Cyrillic Mongolian by the Computer College of Inner Mongolia University

- Manuscripts

- Mongolian Manuscripts from Olon Süme – Yokohama Museum of EurAsian Cultures

- Digitised Mongolian manuscripts – The Royal Library, National Library of Denmark

- Mongolian texts – Digitales Turfan-Archiv, the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities

- Preservation of unique and historic newspapers printed in traditional Mongolian script between 1936-1945 – Endangered Archives Programme, British Library

- Other

- Official Mongolian script version of the People's Daily Online

- Office of the President of Mongolia website in Mongolian script

- Tang, Didi (20 March 2020). "Mongolia abandons Soviet past by restoring alphabet". The Times. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

На других языках

[de] Mongolische Schrift

Die klassische mongolische Schrift war die erste einer ganzen Reihe von mongolischen Schriften, die für die mongolische Sprache entwickelt oder angepasst wurden. Sie wird mit geringfügigen Veränderungen auch heute noch in der Mongolei (seit 1994 wieder neben der kyrillischen Schrift) und in China verwendet, um Mongolisch und Ewenkisch zu schreiben. In China ist die mongolische Schrift dort verbreitet, wo Mongolisch Amtssprache ist, also in der Inneren Mongolei und in Fuxin, Harqin Linker Flügel, im Vorderen Gorlos, in Dorbod, Subei, Teilen von Haixi und Henan sowie in Weichang. Hinzu kommt als offizielle, amtliche Schrift des Westmongolischen das Tôdô Biqig in Bayingolin, Bortala, Hoboksar und Teilen von Haixi.- [en] Mongolian script

Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии

![Folded script style on the coat of arms of Govisümber Province[5]: 427](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d8/Mn_coa_govis%C3%BCmber_aimag.svg/72px-Mn_coa_govis%C3%BCmber_aimag.svg.png)

![''Mandukhai setsen khatan'' (film) [mn] title screen, 1988](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d0/%D0%9C%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B4%D1%83%D1%85%D0%B0%D0%B9_%D1%81%D1%8D%D1%86%D1%8D%D0%BD_%D1%85%D0%B0%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%BD.jpg/120px-%D0%9C%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B4%D1%83%D1%85%D0%B0%D0%B9_%D1%81%D1%8D%D1%86%D1%8D%D0%BD_%D1%85%D0%B0%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%BD.jpg)