lingvo.wikisort.org - Language

Valencian[lower-alpha 1] (valencià)[lower-alpha 2] or Valencian language[4] (llengua valenciana)[lower-alpha 3] is the official, historical and traditional name used in the Valencian Community (Spain), and unofficially in the El Carche comarca in Murcia (Spain),[5][6][7][8] to refer to the Romance language also known as Catalan.[lower-alpha 4][lower-alpha 5][9][10][11][12][13] The Valencian Community's 1982 Statute of Autonomy and the Spanish Constitution officially recognise Valencian as the regional language.[4]

| Valencian | |

|---|---|

| valencià | |

| Pronunciation | [valensiˈa, ba-] |

| Native to | Spain |

| Region | Valencian Community, Murcia (El Carche) See also geographic distribution of Catalan |

| Ethnicity | Valencians |

Native speakers | 2.4 million (2004)[1] |

Language family | |

Writing system | Valencian orthography (Latin script) |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Spain |

Recognised minority language in | Spain

|

| Regulated by | Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua (AVL) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| ISO 639-6 | vlca |

| Glottolog | None |

| IETF | ca-valencia |

| |

| The Catalan / Valencian cultural domain |

|---|

|

As a glottonym, it is used for referring either to the language as a whole[lower-alpha 4][lower-alpha 5] or to the Valencian specific linguistic forms.[lower-alpha 4][lower-alpha 6][14][15] According to philological studies, the varieties of this language spoken in the Valencian Community and El Carche cannot be considered a dialect restricted to these borders: the several dialects of Valencian (Alicante's Valencian, Southern Valencian, Central Valencian or Apitxat, Northern Valencian or Castellon's Valencian and Transitional Valencian) belong to the Western group of Catalan dialects.[16][17] Valencian displays transitional features between Ibero-Romance languages and Gallo-Romance languages. Its similarity with Occitan has led many authors to group it under the Occitano-Romance languages.

There is a political controversy within the Valencian Community regarding its status as a glottonym or as a language on its own, since official reports show that slightly more than half of the people in the Valencian Community consider it as a separate language, different from Catalan, although the same studies show that this percentage decreases dramatically among younger generations and people with higher studies.[18][19] According to the 2006 Statute of Autonomy Valencian is regulated by the Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua,[4] by means of the Castelló norms,[20] which adapt Catalan orthography to Valencian idiosyncrasies. Due to not having been officially recognised for a long time, the number of speakers has severely decreased, and the influence of Spanish has led to the adoption of a huge number of loanwords.[21]

Some of the most important works of Valencian literature experienced a golden age during the Late Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Important works include Joanot Martorell's chivalric romance Tirant lo Blanch, and Ausiàs March's poetry. The first book produced with movable type in the Iberian Peninsula was printed in the Valencian variety.[22][23] The earliest recorded chess game with modern rules for moves of the queen and bishop was in the Valencian poem Scachs d'amor (1475).

Official status

The official status of Valencian is regulated by the Spanish Constitution and the Valencian Statute of Autonomy, together with the Law of Use and Education of Valencian.

Article 6 of the Valencian Statute of Autonomy sets the legal status of Valencian, providing that:[24]

- The native language[lower-alpha 7] of the Valencian Community is Valencian.

- Valencian is official within the Valencian Community, along with Spanish, which is the official language nationwide. Everyone shall have the right to know it and use it, and receive education in Valencian.

- No one can be discriminated against by reason of their language.

- Special protection and respect shall be given to the recuperation of Valencian.

- The Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua shall be the normative institution of the Valencian language.

The Law of Use and Education of Valencian develops this framework, providing for implementation of a bilingual educational system, and regulating the use of Valencian in the public administration and judiciary system, where citizens can freely use it when acting before both.

Valencian is recognised under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages as "Valencian".[25]

Distribution and usage

Distribution

![Following the Reconquista Valencian was spoken much further south than is currently the case, in a situation of bilingualism with Spanish. The latter then gradually imposed itself in many zones, with the limit between the two stabilizing around the mid-18th century. [citation needed]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/15/Evoluci%C3%B3_del_l%C3%ADmit_meridional_del_domini_valenci%C3%A0-catal%C3%A0.svg/220px-Evoluci%C3%B3_del_l%C3%ADmit_meridional_del_domini_valenci%C3%A0-catal%C3%A0.svg.png)

Valencian is not spoken all over the Valencian Community. Roughly a quarter of its territory, equivalent to 10% of the population (its inland part and areas in the extreme south as well), is traditionally Spanish-speaking only, whereas Valencian is spoken to varying degrees elsewhere.

Additionally, it is also spoken by a reduced number of people in El Carche, a rural area in the Region of Murcia adjoining the Valencian Community; nevertheless Valencian does not have any official recognition in this area. Although the Valencian language was an important part of the history of this zone, nowadays only about 600 people are able to speak Valencian in the area of El Carche.[26]

Knowledge and usage

In 2010 the Generalitat Valenciana published a study, Knowledge and Social use of Valencian,[27] which included a survey sampling more than 6,600 people in the provinces of Castellon, Valencia, and Alicante. The survey simply collected the answers of respondents and did not include any testing or verification. The results were:

Valencian was the language "always, generally, or most commonly used":

- at home: 31.6%

- with friends: 28.0%

- in internal business relations: 24.7%

For ability:

- 48.5% answered they speak Valencian "perfectly" or "quite well" (54.3% in the Valencian-speaking areas and 10% in the Spanish-speaking areas)

- 26.2% answered they write Valencian "perfectly" or "quite well" (29.5% in the Valencian-speaking areas and 5.8% in the Spanish-speaking areas)

The survey shows that, although Valencian is still the common language in many areas in the Valencian Community, where slightly more than half of the Valencian population are able to speak it, most Valencians do not usually speak in Valencian in their social relations.

Moreover, according to a survey in 2008, there is a downward trend in everyday Valencian users. The lowest numbers are in the major cities of Valencia and Alicante, where the percentage of everyday speakers is in single figures. All in all, in the 1993–2006 period, the number of speakers fell by 10 per cent. One of the factors cited is the increase in the numbers of immigrants from other countries, who tend to favour using Spanish over local languages; accordingly, the number of residents who claim no understanding of Valencian sharply increased. One curiosity in the heartlands mentioned above, is that most of the children of immigrants go to public school and are therefore taught in Valencian and are far more comfortable speaking this with their friends. However, some children of Valencian speakers go to private schools run by the Church where the curriculum is in Spanish and consequently this becomes their preferred language.[citation needed]

Features of Valencian

![The main dialects of Catalan. Western Catalan block comprises the two dialects of Northwestern Catalan and Valencian.[28][29][30]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/13/Catalan_dialects-en.png/180px-Catalan_dialects-en.png)

Note that this is a list of features of the main forms of Valencian as a group of dialectal varieties that differ from those of other Catalan dialects, particularly from the Central variety of the language. For more general information on the features of Valencian, see Catalan language. There is a great deal of variety within the Valencian Community, and by no means do the features below apply to every local version.

Phonology

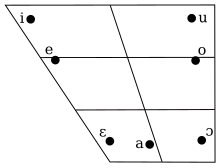

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | |

| Mid | e | o | |

| Open | ɛ | a | ɔ |

- The stressed vowel system of Valencian is the same as that of Eastern Catalan: /a/, /e/, /ɛ/, /i/, /o/, /ɔ/, and /u/, with /ɛ/ and /ɔ/ being considerably lower than in EC.[35]

- The vowels /i/ and /u/ are more open and centralised than in Spanish. This effect is more pronounced in unstressed syllables, where the phones are best transcribed [ɪ, ʊ].[36] As the process is completely predictable, the latter symbols are not used elsewhere in the article.

- The vowel /e/ is somewhat retracted [e̠] and /o/ is somewhat advanced [o̟] both in stressed and unstressed syllables. /e/ and /o/ can be realised as mid vowels [e̞, o̞] in some cases. This occurs more often with /o/.[37]

- The so-called "open vowels", /ɛ/ and /ɔ/, are generally as low as /a/ in most Valencian dialects. The phonetic realisations of /ɛ/ approaches [æ] and /ɔ/ is as open as [ɒ] (as in traditional RP dog). This feature is also found in Balearic.[38]

- /ɛ/ is slightly more open and centralised before liquids /l, r/ and in monosyllabics.

- /ɔ/ is most often a back vowel. In some dialects (including Balearic) /ɔ/ can be unrounded.

- The vowel /a/ is slightly more fronted and closed than in Central Catalan (but less fronted and closed than in Majorcan). The precise phonetic realisation of the vowel /a/ in Valencian is [ɐ ~ ä], this vowel is subject to assimilation in many instances.[39]

- Stressed /a/ can be retracted to [ɑ] in contact with velar consonants (including the velarized [ɫ]), and fronted to [a] in contact with palatals.[39] This is not transcribed in the article.

- Final unstressed /a/ may have the following values: [ɜ ~ ɞ ~ ɐ], depending on the preceding sounds and/or dialect, e.g. taula [ˈtawɫɜ ~ ˈtawɫɞ ~ ˈtawɫɐ] 'table'.

- All vowels are phonetically nasalised between nasal consonants or when preceding a syllable-final nasal.[40]

- Vowels can be lengthened in some contexts.[40]

- There are five general unstressed vowels /a, e, i, o, u/. Although unstressed vowels are more stable than in Eastern Catalan dialects, there are many cases where they merge:[40]

- In some Valencian varieties, unstressed /o/ and /ɔ/ are realised as /u/ before labial consonants (e.g. coberts [kuˈbɛɾ(t)s] 'cutlery'), before a stressed syllable with a high vowel (e.g. sospira [susˈpiɾa] 'he/she sighs') and in some given names (e.g. Josep [dʒuˈzɛp] 'Joseph') (note also in some colloquial speeches initial unstressed /o ~ ɔ/ is often diphthongized to [aw], olor [awˈɫoɾ]) 'smell (n.)'). Similarly, unstressed /e/, and /ɛ/ are realised as /a/ in contact with sibilants, nasals and certain approximants (e.g. eixam [ajˈʃãm] 'swarm', entendre [ãnˈtẽndɾe] 'to understand', clevill [kɫaˈviʎ] 'crevice'). Likewise (although not recommended by the AVL), unstressed /e ~ ɛ/ merges with /i/ in contact with palatal consonants (e.g. genoll [dʒiˈnoʎ] 'knee'), and especially (in this case it is accepted) in lexical derivation with the suffix -ixement (e.g. coneixement [konejʃiˈmẽnt] 'knowledge'). In the Standard all these reductions are accepted (/e, ɛ/ → [i] is only accepted in words with the suffix -ixement).

- Many Valencian dialects, especially Southern Valencian, feature some sort of vowel harmony (harmonia vocàlica). This process is normally progressive (i.e. preceding vowels affect those pronounced afterwards) over the last unstressed vowel of a word; e.g. hora /ˈɔɾa/ > [ˈɔɾɞ] 'hour'. However, there are cases where regressive metaphony occurs over pretonic vowels; e.g. tovallola /tovaˈʎɔla/ > [tɞvɞˈʎɔɫɞ] 'towel', afecta /aˈfɛkta/ > [ɜˈfɛktɜ] 'affects'. Vowel harmony differs greatly from dialect to dialect, while many varieties assimilate both to the height and the quality of the preceding stressed vowel (e.g. terra [ˈtɛrɜ] 'Earth, land' and dona [ˈdɔnɞ] 'woman'); in other varieties, it is just the height that assimilates, so that terra and dona can be pronounced with either [ɜ] ([ˈtɛrɜ, ˈdɔnɜ]) or with [ɞ] ([ˈtɛrɞ, ˈdɔnɞ]), depending on the speaker.

- In a wider sense, vowel harmony can occur in further instances, due to different processes involving palatalisation, velarisarion and labialisation

- In certain cases, the unstressed /a, e/ become silent when followed or preceded by a stressed vowel: quinze anys [kĩnzˈãɲ(t)ʃ].

- In certain accents, vowels occurring at the end of a prosodic unit may be realized as centering diphthongs for special emphasis, so that Eh tu! Vine ací "Hey you! Come here!" may be pronounced [ˈeˈtuə̯ ˈvinea̯ˈsiə̯]. The non-syllabic [a̯] is unrelated to this phenomenon as it is an unstressed non-syllabic allophone of /a/ that occurs after vowels, much like in Spanish.

| Phoneme | Allophone | Usage | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| /a/[39] | |||

| [ä] ~ [ɐ] | - Found in most instances | mà | |

| [a] | - Before/after palatals (*) | nyap | |

| [ã] | - Same than [a], but followed by a nasal | llamp | |

| [ɑ] | - Before/after velars | poal | |

| [ɑ̃] | - Same than [ɑ], but followed by a nasal | sang | |

| [ɐ] | - In unstressed position | abans | |

| [ɐ̃] | - Nasal [ɐ]; that is, [ɐ] followed by or in between nasals | llançat | |

| [ɛ̈] ~ [ɔ̈] | - Final unstressed syllables (vowel harmony) (*) | terra / dona | |

| /ɛ/[42] | |||

| [æ] | - Before liquids and in monosyllabic terms | set | |

| [æ̃] | - Before nasals | dens | |

| [ɛ] | - Rest of cases (*) | terra | |

| /e/[43] | |||

| [e] | - Found in stressed and unstressed syllables | sec | |

| [ẽ] | - In stressed and unstressed position followed by or in between nasals | lent | |

| [a] | - Unstressed position before palatals (*) | eixam | |

| [ɐ̃] | - In some cases, in unstressed position before nasals (*) | entendre | |

| [ɪ] | - Found in the suffix -ixement (*) | naixement | |

| /i/[44] | |||

| [i] | - Especially found in stressed syllables | sis | |

| [ĩ] | - Nasal [i]; that is, [i] followed by or in between nasals | dins | |

| [ɪ] | - Unstressed position | xiquet | |

| [ɪ̃] | - Nasal [ɪ]; that is, [ɪ] followed by or in between nasals | minvar | |

| [j] | - Unstressed position before/after vowels | iogurt | |

| /ɔ/[45] | |||

| [ɒ] | - Found before stops and in monosyllabic terms | roig | |

| [ɒ̃] | - Before nasals | pondre | |

| [ɔ] | - Rest of cases (*) | dona | |

| /o/[46] | |||

| [o] | - Found in stressed and unstressed syllables | molt | |

| [õ] | - Nasal [o]; that is, [o] followed by or in between nasals | on | |

| [o̞] | - Found in the suffix -dor and in coda stressed syllables | cançó | |

| [ʊ] | - Unstressed position before labials, a syllable with a high vowel and in some given names (*) | Josep | |

| [ʊ̃] | - Same as [ʊ], but followed by a nasal | complit | |

| [ew] | - Found in most cases with the weak pronoun ho | ho | |

| /u/[47] | |||

| [u] | - Especially found in stressed syllables | lluç | |

| [ũ] | - Nasal [u]; that is, [u] followed by or in between nasals | fum | |

| [ʊ] | - Unstressed position | sucar | |

| [ʊ̃] | - Nasal [ʊ]; that is, [ʊ] followed by or in between nasals | muntó | |

| [w] | - Unstressed position before/after vowels | teua |

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | (ŋ) | ||||

| Stop | p | b | t | d | k | ɡ | ||

| Affricate | ts | dz | tʃ | dʒ | ||||

| Fricative | f | v | s | z | ʃ | (ʒ) | ||

| Approximant | j | w | ||||||

| Lateral | l | ʎ | ||||||

| Flap | ɾ | |||||||

| Trill | r | |||||||

- The voiced stops /d, ɡ/ are lenited to approximants [ð, ɣ] after a continuant, i.e. a vowel or any type of consonant other than a stop or nasal (exceptions include /d/ after lateral consonants). These sounds are realised as voiceless plosives in the coda in standard Valencian.

- /b/ can also be lenited in betacist dialects.

- /d/ is often elided between vowels following a stressed syllable (found notably in feminine participles, /ada/ → [aː], and in the suffix -dor); e.g. fideuà [fiðeˈwaː] ( < fideuada) ' fideuà', mocador [mokaˈoɾ] 'tissue' (note this feature, although widely spread in South Valencia, is not recommended in standard Valencian,[34] except for reborrowed terms such as Albà, Roà, the previously mentioned fideuà, etc.).

- Unlike other Catalan dialects, the clusters /bl/ and /ɡl/ never geminate or fortify in intervocalic position (e.g. poble [ˈpɔbɫe] 'village').

- The velar stops /k/, /ɡ/ are fronted to pre-velar position [k̟, ɡ̟] before front vowels: qui [ˈk̟i] ('who').

- Valencian has preserved in most of its varieties the mediaeval voiced pre-palatal affricate /dʒ/ (similar to the j in English "jeep") in contexts where other modern dialects have developed fricative consonants /ʒ/ (like the si in English "vision"), e.g. dijous [diˈdʒɔws] ('Thursday').

- Note the fricative [ʒ] appears only as a voiced allophone of /ʃ/ before vowels and voiced consonants; e.g. peix al forn [ˈpejʒ aɫ ˈfoɾn] 'oven fish'.

- Unlike other Catalan dialects, /dʒ/ and /tʃ/ do not geminate (in most accents): metge [ˈmedʒe] ('medic'), and cotxe [ˈkotʃe] ('car'). Exceptions may include learned terms like pidgin [ˈpidːʒĩn] ('pidgin').

- In the Standard, intervocalic /dz/, e.g. setze ('sixteen'), and /ts/, e.g. potser ('maybe'), are recommended to be pronounced with a gemination of the stop element (/dːz/ and /tːs/, respectively).

- /v/ occurs in Balearic,[48] Alguerese, standard Valencian and some areas in southern Catalonia (e.g. viu [ˈviw], 's/he lives').[49] It has merged with /b/ elsewhere.[50]

- /v/ is realized as an approximant [ʋ] after continuants: avanç [aˈʋans] ('advance'). This is not transcribed in this article.

- Deaffrication of /dz/ to [z] in verbs ending in -itzar and derivatives: analitzar [anaɫiˈzaɾ] ('to analise'), organització [oɾɣanizaˈsjo] ('organization'). Also in words like botzina [boˈzina] ('horn'), horitzó [oɾiˈzo] ('horizon') and magatzem [maɣaˈzẽm] ('storehouse') (c.f. guitza [ˈɡidːza], 'bother').

- Most varieties of Valencian preserve final stops in clusters (e.g. /mp/, /nt/, /ŋk/, and /lt/): camp [ˈkãmp] 'field' (a feature shared with modern Balearic). Dialectally, all final clusters can be simplified.

- /l/ is normally velarised ([ɫ]), especially in the coda.

- /l/ is generally dropped in the word altre [ˈatɾe] ('other'), as well as in derived terms.[34]

- /r/ is mostly retained in the coda (e.g. estar [esˈtaɾ], 'to be'), except for some cases where it is dropped: arbre [ˈabɾe] ('tree") and diners [diˈnes] ('money').[34] In some dialects /r/ can be further dropped in combinatory forms with infinitives and pronouns.

- In some dialects, /s/ is pronounced [sʲ] or [ʃ] after /i, j, ʎ, ɲ/. In the Standard only is accepted after /i/ (in the inchoative form with /sk/ → [ʃk]), and after /ʎ, ɲ/: ells [ˈeʎʃ] ('they'). In some variants the result may be an affricate.[51]

Morphology

- The present first-person singular of verbs differs from Central Catalan. All those forms without final -o are more akin to mediaeval Catalan and contemporary Balearic Catalan.

| Stem | Infinitive | Present first person singular | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catalan | English | Valencian | Central | English | |||

| IPA | IPA | ||||||

| -ar | parlar | to speak | parle | [ˈpaɾɫe] | parlo | [ˈpaɾɫu] | I speak |

| -re | batre | to beat | bat | [ˈbat] | bato | [ˈbatu] | I beat |

| -er | témer | to fear | tem | [ˈtẽm] | temo | [ˈtemu] | I fear |

| -ir | sentir | to feel | sent | [ˈsẽnt] | sento | [ˈsẽntu] | I feel |

| senc | [ˈsẽŋk] | ||||||

| inchoative -ir | patir | to suffer | patisc | [paˈtisk] | pateixo | [pəˈtɛʃu] | I suffer |

| patesc | [paˈtesk] | ||||||

- Present subjunctive is more akin to medieval Catalan and Spanish; -ar infinitives end ⟨e⟩, -re, -er and -ir verbs end in ⟨a⟩ (in contemporary Central Catalan present subjunctive ends in ⟨i⟩).

- An exclusive feature of Valencian is the subjunctive imperfect morpheme -ra: que ell vinguera ('that he might come').

- Valencian has -i- as theme vowel for inchoative verbs of the third conjugation; e.g. servix ('s/he serves'), like North-Western Catalan. Although, again, this cannot be generalised since there are Valencian dialects that utilize -ei-, e.g. serveix.

- In Valencian the simple past tense (e.g. cantà 'he sang') is more frequently used in speech than in Central Catalan, where the periphrastic past (e.g. va cantar 'he sang') is prevailing and the simple past mostly appears in written language. The same, however, may be said of the Balearic dialects.[52]

- The second-person singular of the present tense of the verb ser ('to be'), ets ('you are'), has been replaced by eres in colloquial speech.

- The infinitive veure ('to see') has the variant vore, which belongs to more informal and spontaneous registers.

- The usage of the periphrasis of obligation tindre + que + infinitive is widely spread in colloquial Valencian, instead of the Standard haver + de (equivalent to English "have to").

- Clitics

- In general, use of modern forms of the determinate article (el, els 'the') and the third-person unstressed object pronouns (el, els 'him, them'), though some dialects (for instance the one spoken in Vinaròs area) preserve etymological forms lo, los as in Lleida. For the other unstressed object pronouns, etymological old forms (me, te, se, ne, mos, vos...) can be found, depending on places, in conjunction with the more modern reinforced ones (em, et, es, en, ens, us...).

- The adverbial pronoun hi ('there') is almost never used in speech and is replaced by other pronouns. The adverbial pronoun en ('him/her/them/it') is used less than in Catalonia and the Balearic Islands.[52]

- Combined weak clitics with li ('him/her/it') preserve the li, whereas in Central Catalan it is replaced by hi. For example, the combination li + el gives li'l in Valencian (l'hi in Central Catalan).

- The weak pronoun ho ('it') is pronounced as:

- [ew], when it forms syllable with a pronoun: m'ho dóna [mew ˈðona], dóna-m'ho [ˈdonamew] ('s/he gives it to me')

- [ew] or [u], when it comes before a verb starting with consonant: ho dóna [ew ˈðona] (or [u ˈðona]) ('s/he gives it')

- [w], when precedes a vowel or when coming after a vowel: li ho dóna [liw ˈðona] ('s/he gives it to her/him'), dóna-ho [ˈdonaw] ('you give it')

- [o], when it comes after a consonant or a semivowel: donar-ho [doˈnaɾo] ('to give it').

- The personal pronoun jo ('I') and the adverb ja ('already') are not pronounced according to the spelling, but to the etymology ([ˈjɔ] and [ˈja], instead of /ˈ(d)ʒɔ/ and /ˈ(d)ʒa/). Similar pronunciations can be heard in North-Western Catalan and Ibizan.

- The preposition amb ('with') merges with en ('in') in most Valencian dialects.

- Valencian preserves the mediaeval system of demonstratives with three different levels of demonstrative precision (este or aquest/açò/ací, eixe or aqueix/això/ahí, aquell/allò/allí or allà, where aquest and aqueix are almost never used) (feature shared with modern Ribagorçan and Tortosan).

Vocabulary

Valencian vocabulary contains words both restricted to the Valencian-speaking domain, as well as words shared with other Catalan varieties, especially with Northwestern ones. Words are rarely spread evenly over the Valencian community, but are usually contained to parts of it, or spread out into other dialectal areas. Examples include hui 'today' (found in all of Valencia except transitional dialects, in Northern dialects avui) and espill 'mirror' (shared with Northwestern dialects, Central Catalan mirall). There is also variation within Valencia, such as 'corn', which is dacsa in Central and Southern Valencian, but panís in Alicante and Northern Valencian (as well as in Northwestern Catalan). Since Standard Valencian is based on the Southern dialect, words from this dialect are often used as primary forms in the standard language, despite other words traditionally being used in other Valencian dialects. Examples of this are tomaca 'tomato' (which is tomata outside of Southern Valencian) and matalaf 'mattress' (which is matalap in most of Valencia, including parts of the Southern Valencian area).

Below are a selection of words which differ or have different forms in Standard Valencian and Catalan. In many cases, both standards include this variation in their respective dictionaries, but differ as to what form is considered primary. In other cases, Valencian includes colloquial forms not present in the IEC standard. Primary forms in each standard are shown in bold (and may be more than one form). Words in brackets are present in the standard in question, but differ in meaning from how the cognate is used in the other standard.

| Standard Valencian (AVL)[53] | Standard Catalan (IEC)[54] | English |

|---|---|---|

| així, aixina | així | like this |

| bresquilla, préssec | préssec, bresquilla | peach |

| creïlla, patata | patata, creïlla | potato |

| dènou, dèneu, dinou | dinou, dènou | nineteen |

| dos, dues | dues, dos | two (f.) |

| eixe, aqueix | aqueix, eixe | that |

| eixir, sortir | sortir, eixir | to exit, leave |

| engrunsadora, gronxador(a) | gronxador(a) | swing |

| espill, mirall | mirall, espill | mirror |

| este, aquest | aquest, este | this |

| estel, estrela, estrella | estel, estrella, estrela | star |

| hòmens, homes | homes | men (plural) |

| hui, avui | avui, hui | today |

| huit, vuit | vuit, huit | eight |

| lluny, llunt | lluny | far |

| meló d'Alger, meló d'aigua, síndria | síndria, meló d'aigua, meló d'Alger | watermelon |

| meua, meva teua, teva seua, seva | meva, meua teva, teua seva, seua | my, mine your(s) his/her(s)/its |

| mitat, meitat | meitat, mitat | half |

| palometa, papallona | papallona, palometa | butterfly |

| per favor | si us plau, per favor | please |

| periodista, periodiste (-a) | periodista | journalist |

| polp, pop | pop, polp | octopus |

| quint, cinqué | cinquè, quint | fifth |

| rabosa, guineu | guineu, rabosa | fox |

| roí(n), dolent | dolent, roí | bad, evil |

| roig, vermell | vermell, roig | red |

| sext, sisé | sisè, sext | sixth |

| tindre, tenir | tenir, tindre | to have |

| tomaca, tomàquet, tomata | tomàquet, tomaca, tomata | tomato |

| vacacions, vacances | vacances, vacacions | holidays |

| veure, vore | veure | to see |

| vindre, venir | venir, vindre | to come |

| xicotet, petit | petit, xicotet | small |

Varieties of Valencian

Standard Valencian

The Academy of Valencian Studies (Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua, AVL), established by law in 1998 by the Valencian autonomous government and constituted in 2001, is in charge of dictating the official rules governing the use of Valencian.[55] Currently, the majority of people who write in Valencian use this standard.[56]

Standard Valencian is based on the standard of the Institute of Catalan Studies (Institut d'Estudis Catalans, IEC), used in Catalonia, with a few adaptations.[57] This standard roughly follows the Rules of Castelló (Normes de Castelló) from 1932,[58] a set of othographic guidelines regarded as a compromise between the essence and style of Pompeu Fabra's guidelines, but also allowing the use of Valencian idiosyncrasies.

Valencian dialects

- Transitional Valencian (valencià de transició) or Tortosan (tortosí): spoken only in the northernmost areas of the province of Castellon in towns like Benicarló or Vinaròs, the area of Matarranya in Aragon (province of Teruel), and a southern border area of Catalonia surrounding Tortosa, in the province of Tarragona.

- Word-initial and postconsonantal /dʒ/ (Catalan /ʒ/ and /dʒ/~/ʒ/) alternates with [(j)ʒ] intervocalically; e.g. joc [ˈdʒɔk] ('game'), but pitjor [piˈʒo] ('worse'), boja [ˈbɔjʒa] ('crazy') (Standard Valencian /ˈdʒɔk/, /piˈdʒoɾ/; /ˈbɔdʒa/; Standard Catalan /ˈʒɔk/, /piˈdʒo/ and /ˈbɔʒə/).

- Final ⟨r⟩ [ɾ] is not pronounced in infinitives; e.g. cantar [kãnˈta] (Standard /kanˈtaɾ/) ('to sing').

- Archaic articles lo, los ('the') are used instead of el, els; e.g. lo xic ('the boy'), los hòmens ('the men').

- Northern Valencian (valencià septentrional) or Castellon's Valencian (valencià castellonenc): spoken in an area surrounding the city of Castellón de la Plana.

- Use of [e] sound instead of standard ⟨a⟩ /a/ in the third person singular of most verbs; e.g. (ell) cantava [kãnˈtave] (Standard /kanˈtava/) 'he sang'. Thus, Northern Valencian dialects contrast forms like (jo) cantava [kãnˈtava] ('I sang') with (ell) cantava [kãnˈtave] ('he sang'), but merges (jo) cante [ˈkãnte] ('I sing') with (ell) canta [ˈkãnte] ('he sings').

- Palatalization of ⟨ts⟩ /ts/ > [tʃ] and ⟨tz⟩ /dz/ > [dːʒ]; e.g. pots /ˈpots/ > [ˈpotʃ] ('cans, jars, you can'), dotze /ˈdodze/ > [ˈdodːʒë] ('twelve').

- Depalatalization of /jʃ/ to [jsʲ] by some speakers; e.g. caixa /ˈkajʃa/ > [ˈkajsʲa] ('box').

- Central Valencian (valencià central), or Apitxat, spoken in Valencia city and its area, but not used as standard by the Valencian media.

- Sibilant merger: all voiced sibilants are devoiced (/dʒ/ > [tʃ], /dz/ > [ts], /z/ > [s]); that is, apitxat pronounces casa [ˈkasa] ('house') and joc [ˈtʃɔk] ('game'), where other Valencians would pronounce /ˈkaza/ and /ˈdʒɔk/ (feature shared with Ribagorçan).

- Betacism, that is the merge of /v/ into /b/; e.g. viu [ˈbiw] (instead of /ˈviw/) ('he lives').

- Fortition (gemination) and vocalisation of final consonants; nit [ˈnitː(ə)] (instead of /ˈnit/) ('night').

- It preserves the strong simple past, which has been substituted by an analytic past (periphrastic past) with vadere + infinitive in the rest of modern Catalan and Valencian variants. For example, aní instead of vaig anar ('I went').

- Southern Valencian (valencià meridional): spoken in the contiguous comarques located in the southernmost part of the Valencia province and the northernmost part in the province of Alicante. This dialect is considered as Standard Valencian.

- Vowel harmony: the final syllable of a disyllabic word adopts a preceding open ⟨e⟩ ([ɜ]) or ⟨o⟩ ([ɞ]) if the final vowel is an unstressed -⟨a⟩ or -⟨e⟩; e.g. terra [ˈtɛrɜ] ('earth, land'), dona [ˈdɔnɞ] ('woman').

- This dialect retain geminate consonants (⟨tl⟩ /lː/ and ⟨tn⟩ /nː/); e.g. guatla [ˈɡʷaɫːa] ('quail'), cotna [ˈkõnːa] ('rind').

- Weak pronouns are "reinforced" in front of the verb (em, en, et, es, etc.) contrary to other dialects which maintains "full form" (me, ne, te, se, etc.).

- Alicante's Valencian (valencià alacantí): spoken in the southern half of the province of Alicante, and the area of El Carche in Murcia.

- Intervocalic /d/ elision in most instances; e.g. roda [ˈrɔa] ('wheel'), nadal [naˈaɫ] ('Christmas').

- Yod is not pronounced in ⟨ix⟩ /jʃ/ > [ʃ]; e.g. caixa [ˈkaʃa] ('box').

- Final ⟨r⟩ is not pronounced in infinitives; e.g. cantar [kãnˈta] ('to sing').

- There are some archaisms like: ans instead of abans ('before'), manco instead of menys ('less'), dintre instead of dins ('into') or devers instead of cap a ('towards').

- There are more interferences with Spanish than other dialects: assul (from azul) instead of blau (or atzur) ('blue'), llimpiar (from limpiar) instead of netejar ('to clean') or sacar (from sacar) instead of traure ('take out').

Authors and literature

Middle Ages

- Misteri d'Elx (c. 1350). Liturgical drama. Listed as Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO.

Renaissance

- Ausiàs March (Gandia, 1400 – Valencia, 3 March 1459). Poet, widely read in renaissance Europe.

- Joanot Martorell (Gandia, 1413–1468). Knight and the author of the novel Tirant lo Blanch.

- Isabel de Villena (Valencia, 1430–1490). Religious poet.

- Joan Roís de Corella (Gandia or Valencia, 1435 – Valencia, 1497). Knight and poet.

- Obres e trobes en lahors de la Verge Maria (1474) The first book printed in Spain. It is the compendium of a religious poetry contest held that year in the town of Valencia.[23]

Media in Valencian

Until its dissolution in November 2013, the public-service Ràdio Televisió Valenciana (RTVV) was the main broadcaster of radio and television in Valencian language. The Generalitat Valenciana constituted it in 1984 in order to guarantee the freedom of information of the Valencian people in their own language.[59] It was reopened again in 2018 in the same location but under a different name, À Punt, and it is owned by À Punt Media, a group owned by the Generalitat Valenciana. The new television channel claims to be plural, informative and neutral for all of the Valencian population. It is bilingual, with a focus on the Valencian language. It's recognised as a regional TV channel.[60]

Prior to its dissolution, the administration of RTVV under the People's Party (PP) had been controversial due to accusations of ideological manipulation and lack of plurality. The news broadcast was accused of giving marginal coverage of the Valencia Metro derailment in 2006 and the indictment of President de la Generalitat Francisco Camps in the Gürtel scandal in 2009.[61] Supervisors appointed by the PP were accused of sexual harassment.[62]

In face of an increasing debt due to excessive expenditure by the PP, RTVV announced in 2012 a plan to shed 70% of its labour. The plan was nullified on 5 November 2013 by the National Court after trade unions appealed against it. On that same day, the President de la Generalitat Alberto Fabra (also from PP) announced RTVV would be closed, claiming that reinstating the employees was untenable.[63] On 27 November, the legislative assembly passed the dissolution of RTVV and employees organised to take control of the broadcast, starting a campaign against the PP. Nou TV's last broadcast ended abruptly when Spanish police pulled the plug at 12:19 on 29 November 2013.[64]

Having lost all revenues from advertisements and facing high costs from the termination of hundreds of contracts, critics question whether the closure of RTVV has improved the financial situation of the Generalitat, and point out to plans to benefit private-owned media.[65] Currently, the availability of media in the Valencian language is extremely limited. All the other autonomous communities in Spain, including the monolingual ones, have public-service broadcasters, with the Valencian Community being the only exception despite being the fourth most populated.

In July 2016 a new public corporation, Valencian Media Corporation, was launched in substitution of RTVV. It manages and controls several public media in the Valencian Community, including the television channel À Punt, which started broadcasting in June 2018.

Politico-linguistic controversy

Linguists, including Valencian scholars, deal with Catalan and Valencian as the same language. The official regulating body of the language of the Valencian community, the Valencian Language Academy (Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua, AVL) considers Valencian and Catalan to be two names for the same language.[66]

[T]he historical patrimonial language of the Valencian people, from a philological standpoint, is the same shared by the autonomous communities of Catalonia and Balearic Islands, and Principality of Andorra. Additionally, it is the patrimonial historical language of other territories of the ancient Crown of Aragon [...] The different varieties of these territories constitute a language, that is, a "linguistic system" [...] From this group of varieties, Valencian has the same hierarchy and dignity as any other dialectal modality of that linguistic system [...]

— Ruling of the Valencian Language Academy of 9 February 2005, extract of point 1.[58][lower-alpha 8]

The AVL was established in 1998 by the PP-UV government of Eduardo Zaplana. According to El País, Jordi Pujol, then president of Catalonia and of the CiU, negotiated with Zaplana in 1996 to ensure the linguistic unity of Catalan in exchange for CiU support of the appointment of José María Aznar as Prime Minister of Spain.[67] Zaplana has denied this, claiming that "[n]ever, never, was I able to negotiate that which is not negotiable, neither that which is not in the negotiating scope of a politician. That is, the unity of the language".[lower-alpha 9]

The AVL orthography is based on the Normes de Castelló, a set of rules for writing Valencian established in 1932. A rival set of rules, called Normes del Puig, were established in 1979 by the Royal Academy of Valencian Culture (Real Acadèmia de Cultura Valenciana, RACV), which considers itself a rival language academy to the AVL, and promotes an alternative orthography. Compared to Standard Valencian, this orthography excludes many words not traditionally used in the Valencian Community, and also prefers spellings such as ⟨ch⟩ for /tʃ/ and ⟨y⟩ for /j/ (as in Spanish).

Valencian is classified as a Western dialect, along with the North-Western varieties spoken in Western Catalonia (Province of Lleida and most of the Province of Tarragona).[68][69] The various forms of Catalan and Valencian are mutually intelligible (ranging from 90% to 95%)[70]

Despite the position of the official organizations, an opinion poll carried out between 2001 and 2004[19] showed that the majority (65%) of the Valencian people (both Valencian and Spanish speakers) consider Valencian different from Catalan: this position is promoted by people who do not use Valencian regularly.[71] Furthermore, the data indicate that younger people educated in Valencian are much less likely to hold these views. According to an official poll in 2014,[18] 52% of Valencians considered Valencian to be a language different from Catalan, while 41% considered the languages to be the same. This poll showed significant differences regarding age and level of education, with a majority of those aged 18–24 (51%) and those with a higher education (58%) considering Valencian to be the same language as Catalan. This can be compared to those aged 65 and above (29%) and those with only primary education (32%), where the same view has its lowest support.

The ambiguity regarding the term Valencian and its relation to Catalan has sometimes led to confusion and controversy. In 2004, during the drafting of the European Constitution, the regional governments of Spain where a language other than Spanish is co-official were asked to submit translations into the relevant language in question. Since different names are used in Catalonia ("Catalan") and in the Valencian Community ("Valencian"), the two regions each provided one version, which were identical to each other.[72]

See also

- Pluricentric language

- Valencian Sign Language

- Che (interjection) § Other uses (spelled xe in Modern Valencian)

- Similar linguistic controversies:

- Andalusian language movement

- Names given to the Spanish language

- Moldovan language

- Occitan language

- Serbo-Croatian

Notes

- English pronunciation: /vəˈlɛnsiən, -nʃən/.

- Valencian pronunciation: [valensiˈa, ba-].

Catalan pronunciation: [bələnsiˈa, və-] (Central and Insular), [balensiˈa] (North-western). - Also known as idioma valencià.

- The Valencian Normative Dictionary of the Valencian Academy of the Language states that Valencian is a "romance language spoken in the Valencian Community, as well as in Catalonia, the Balearic Islands, the French department of the Pyrénées-Orientales, the Principality of Andorra, the eastern flank of Aragon and the Sardinian town of Alghero (unique in Italy), where it receives the name of 'Catalan'."

- The Catalan Language Dictionary of the Institut d'Estudis Catalans states in the sixth definition of Valencian that it is equivalent to Catalan language in the Valencian community.

- The Catalan Language Dictionary of the Institut d'Estudis Catalans states in the second definition of Valencian that it is the Western dialect of Catalan spoken in the Valencian Community.

- The original text says "llengua pròpia", a term that does not have an equivalent in English.

- Original full text of Dictamen 1: D’acord amb les aportacions més solvents de la romanística acumulades des del segle XIX fins a l’actualitat (estudis de gramàtica històrica, de dialectologia, de sintaxi, de lexicografia…), la llengua pròpia i històrica dels valencians, des del punt de vista de la filologia, és també la que compartixen les comunitats autònomes de Catalunya i de les Illes Balears i el Principat d’Andorra. Així mateix és la llengua històrica i pròpia d’altres territoris de l’antiga Corona d’Aragó (la franja oriental aragonesa, la ciutat sarda de l’Alguer i el departament francés dels Pirineus Orientals). Els diferents parlars de tots estos territoris constituïxen una llengua, és a dir, un mateix "sistema lingüístic", segons la terminologia del primer estructuralisme (annex 1) represa en el Dictamen del Consell Valencià de Cultura, que figura com a preàmbul de la Llei de Creació de l’AVL. Dins d’eixe conjunt de parlars, el valencià té la mateixa jerarquia i dignitat que qualsevol altra modalitat territorial del sistema lingüístic, i presenta unes característiques pròpies que l’AVL preservarà i potenciarà d’acord amb la tradició lexicogràfica i literària pròpia, la realitat lingüística valenciana i la normativització consolidada a partir de les Normes de Castelló.

- "Nunca, nunca, pude negociar lo que no se puede negociar, ni aquello que no está en el ámbito de la negociación de un político. Es decir la unidad de la lengua."

References

- Luján, Míriam; Martínez, Carlos D.; Alabau, Vicente. Evaluation of several Maximum Likelihood Linear Regression variants for language adaptation (PDF). Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation, LREC 2008. p. 860.

the total number of people who speak Catalan is 7,200,000, (...). The Valencian dialect is spoken by 27% of all Catalan speakers.

citing Vilajoana, Jordi, and Damià Pons. 2001. Catalan, Language of Europe. Generalitat de Catalunya, Department de Cultura. Govern de les Illes Balears, Conselleria d’Educació i Cultura. - Some Iberian scholars may alternatively classify Catalan as Iberian Romance/East Iberian.

- Wheeler 2006.

- "Ley Orgánica 1/2006, de 10 de abril, de Reforma de la Ley Orgánica 5/1982, de 1 de julio, de Estatuto de Autonomía de la Comunidad Valenciana" (PDF). Generalitat Valenciana. 10 April 2006. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua (23 July 2013). "El valencià continua viu en la comarca murciana del Carxe". avl.gva.es (in Valencian). Archived from the original on 13 September 2014. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- "El valenciano 'conquista' El Carche". La Opinión de Murcia. 12 February 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- Miquel Hernandis (21 February 2016). "En Murcia quieren hablar valenciano". El Mundo. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- "La AVL publica una 'Gramàtica Valenciana Bàsica' con las formas más "genuinas" y "vivas" de su tradición histórica". 20minutos.es. Europa Press. 22 April 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- "Valenciano, na". Diccionario de la Real Academia Española (in Spanish). Real Academia Española. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- "Dictamen sobre los Principios y Criterios para la Defensa de la Denominación y entidad del Valenciano" (PDF).

It is a fact the in Spain there are two equally legal names for referring to this language: Valencian, as stated by the Statute of Autonomy of the Valencian Community, and Catalan, as recognised in the Statutes of Catalonia and Balearic Islands.

- «Otra sentencia equipara valenciano y catalán en las oposiciones, y ya van 13.» 20 minutos, 7 January 2008.

- Decreto 84/2008, de 6 de junio, del Consell, por el que se ejecuta la sentencia de 20 de junio de 2005, de la Sala de lo Contencioso-Administrativo del Tribunal Superior de Justicia de la Comunitat Valenciana.

- "no trobat". sindicat.net.

- Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua (9 February 2005). "Acord de l'Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua (AVL), adoptat en la reunió plenària del 9 de febrer del 2005, pel qual s'aprova el dictamen sobre els principis i criteris per a la defensa de la denominació i l'entitat del valencià" (PDF) (in Valencian). p. 52. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- Institut d'Estudis Catalans. "Resultats de la consulta:valencià". DIEC 2 (in Valencian). Retrieved 23 February 2016.

2 6 m. [FL] Al País Valencià, llengua catalana.

- Alcover, Antoni Maria (1983). Per la llengua (in Catalan). Barcelona. p. 37. ISBN 9788472025448. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- Moll, Francesc de Borja (1968). Gramàtica catalana: Referida especialment a les Illes Balears [Catalan grammar: Referring especially to the Balearic Islands] (in Catalan). Palma de Mallorca: Editorial Moll. pp. 12–14. ISBN 84-273-0044-1.

- Baròmetre d'abril 2014 (PDF) (Report). Presidència de la Generalitat Valenciana. 2014. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- "Casi el 65% de los valencianos opina que su lengua es distinta al catalán, según una encuesta del CIS" [Almost 65% of Valencians think that their language is different from Catalan, according to a CIS survey]. La Vanguardia. 9 December 2004. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- "Ley 7/1998, de 16 de septiembre, de Creación de la Academia Valenciana de la Lengua" (in Spanish) – via Boletín Oficial de España.

- Casanova, Emili (1980). "Castellanismos y su cambio semántico al penetrar en el catalán" (PDF). Boletín de la Asociación Europea de Profesores de Español. 12 (23): 15–25.

- Trobes en llaors de la Verge Maria ("Poems of praise of the Virgin Mary") 1474.

- Costa Carreras & Yates 2009, pp. 6–7.

- "Título I. La Comunitat Valenciana – Estatuto Autonomía". Congreso.es. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- "Aplicación de la Carta en España, Segundo ciclo de supervisión. Estrasburgo, 11 de diciembre de 2008. A.1.3.28 pag 7; A.2.2.5" (PDF). Coe.int. p. 107. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- Martínez, D. (26 November 2011). "Una isla valenciana en Murcia" [A Valencian island in Murcia]. ABC (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- "Servei d'Investigació i Estudis Sociolingüístics (Knowledge and Social use of Valencian language)". Servei d’Investigació i Estudis Sociolingüístics. 2010. Archived from the original on 10 December 2010. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- Feldhausen 2010, p. 6.

- Wheeler 2005, p. 2.

- Costa Carreras & Yates 2009, p. 4.

- Saborit Vilar 2009, p. 23.

- Saborit Vilar 2009, p. 52.

- Lacreu i Cuesta, Josep (2002), "Valencian", Manual d'ús de l'estàndard oral [Manual for the use of the oral standard] (6th ed.), Valencia: Universitat de València, pp. 40–4, ISBN 84-370-5390-0.

- "L'estàndard oral del valencià (2002)" (PDF). Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2010.

- Recasens 1996, p. 58.

- Recasens 1996, pp. 65–69, 141–142.

- Recasens 1996, pp. 69–77, 135–140.

- Recasens 1996, pp. 81–90, 130–133.

- Recasens 1996, pp. 90–104.

- Recasens 1996, pp. 59–142.

- Saborit Vilar 2009, p. ?.

- Recasens 1996, pp. 81–90.

- Recasens 1996, pp. 69–77.

- Recasens 1996, pp. 65–69.

- Recasens 1996, pp. 130–133.

- Recasens 1996, pp. 135–140.

- Recasens 1996, pp. 141–142.

- Carbonell & Llisterri 1992, p. 53.

- Veny 2007, p. 51.

- Wheeler 2005, p. 13.

- Recasens 2014, pp. 253–254.

- Badia i Margarit, Antoni M. (1995). Gramática de la llengua catalana: Descriptiva, normativa, diatópica, diastrática (in Catalan). Barcelona: Proa.

- Diccionari Normatiu Valencià. http://www.avl.gva.es/lexicval/

- Diccionari de la llengua catalana, Segona edició. http://dlc.iec.cat/index.html

- Statute of Autonomy of the Valencian Community, article 6, section 4.

- Lledó 2011, p. 339.

- Lledó 2011, p. 338.

- Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua 2005.

- "Ley de Creación de la Entidad Pública Radiotelevisión Valenciana" (PDF). UGT RTTV. 1984. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- "Benvinguts a À Punt. L'espai públic de comunicació valencià". À Punt.

- "Los escándalos de Canal 9". vertele.com. 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- "Sanz, destituït de secretari general de RTVV per assetjament sexual". Vilaweb. 2010. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- Bono, Ferran (2013). "El fracaso de Fabra acaba con el PP". El País. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- "Polic evict staff in Spain after closure of station". BBC. 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- "El coste del cierre de RTVV asciende a 144,1 millones". Levante-EMV. 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- "Dictamen de l'Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua sobre els principis i criteris per a la defensa de la denominació i l'entitat del valencià". Report from Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua about denomination and identity of Valencian.

- "Pujol revela que pactó con Zaplana para avanzar con discreción en la unidad del catalán". El País (in Spanish). Barcelona / Valencia. 10 November 2004. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- Feldhausen 2010, p. 5.

- Wheeler 2005, pp. 2–3.

- Central Catalan has 90% to 95% inherent intelligibility for speakers of Valencian (1989 R. Hall, Jr.), cited on Ethnologue.

- Wheeler 2003, p. 207.

- Isabel I Vilar, Ferran (30 October 2004). "Traducció única de la Constitució europea". I-Zefir. Retrieved 29 April 2009.

Bibliography

- Carbonell, Joan F.; Llisterri, Joaquim (1992). "Catalan". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 22 (1–2): 53. doi:10.1017/S0025100300004618. S2CID 249411809.

- Colomina i Castanyer, Jordi, (1995). Els valencians i la llengua normativa. Textos universitaris. Alicante: Institut de Cultura "Juan Gil-Albert". ISBN 84-7784-178-0.

- Costa Carreras, Joan; Yates, Alan (2009). The Architect of Modern Catalan: Selected Writings/Pompeu Fabra (1868–1948). Instutut d'Estudis Catalans & Universitat Pompeu Fabra & Jonh Benjamins B.V. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-90-272-3264-9.

- Guinot, Enric (1999). Els fundadors del Regne de València. Edicions 3i4, Valencia 1999. ISBN 84-7502-592-7

- Lledó, Miquel Àngel (2011). "26. The Independent Standardization of Valencia: From Official Use to Underground Resistance". Handbook of Language and Ethnic Identity : The Success-Failure Continuum in Language and Ethnic Identity Efforts (Volume 2). New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 336–348. ISBN 978-0-19-539245-6.

- Feldhausen, Ingo (2010). Sentential Form and Prosodic Structure of Catalan. John Benjamins B.V. ISBN 978-90-272-5551-8.Salvador i Gimeno, Carles (1951). Gramàtica valenciana. Associació Cultural Lo Rat Penat. Valencia 1995. ISBN 84-85211-71-5.

- Recasens Vives, Daniel (1996) [1991], Fonètica descriptiva del català: assaig de caracterització de la pronúncia del vocalisme i el consonantisme català al segle XX, Biblioteca Filològica (in Catalan), vol. 21 (2nd ed.), Barcelona. Spain: Institut d'Estudis Catalans, ISBN 978-84-7283-312-8

- Recasens Vives, Daniel (2014), Fonètica i fonologia experimentals del català (in Catalan), Barcelona. Spain: Institut d'Estudis Catalans

- Saborit Vilar, Josep (2009), Millorem la pronúncia, Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua

- Salvador i Gimeno, Carles (1963). Valencians i la llengua autòctona durant els segles XVI, XVII i XVIII. Institució Alfons el Magnànim. Valencia. ISBN 84-370-5334-X.

- Sanchis i Guarner, Manuel (1934, 1967). La llengua dels valencians. Edicions 3i4, Valencia 2005. ISBN 84-7502-082-8 .

- Valor i Vives, Enric (1973). Curs mitjà de gramàtica catalana, referida especialment al País Valencià. Grog Editions, Valencia 1999. ISBN 84-85211-45-6 .

- Veny, Joan (2007). Petit Atles lingüístic del domini català. Vol. 1 & 2. Barcelona: Institut d'Estudis Catalans. p. 51. ISBN 978-84-7283-942-7.

- Wheeler, Max; Yates, Alan; Dols, Nicolau (1999). Catalan: A Comprehensive Grammar. London: Routledge.

- Wheeler, Max (2003). "5. Catalan". The Romance Languages. London: Routledge. pp. 170–208. ISBN 0-415-16417-6.

- Wheeler, Max (2005). The Phonology of Catalan. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-19-925814-7.

- Wheeler, Max H. (2006). "Catalan". Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-044299-0.

External links

- Documents

- Disputing theories about Valencian origin (in Spanish)

- The origins and evolution of language secessionism in Valencia. An analysis from the transition period until today

- Article from El País (25 October 2005) regarding report on use of Valencian published by Servei d’Investicació i Estudis Sociolinguístics (in Spanish)

На других языках

- [en] Valencian language

[es] Idioma valenciano

El valenciano (autoglotónimo, valencià)[5] es una lengua romance hablada en la Comunidad Valenciana (España) y en El Carche (Región de Murcia), así como en Cataluña, Islas Baleares, Andorra, la Franja de Aragón, el condado de Rosellón y la ciudad sarda del Alguer, donde recibe el nombre de catalán.[6][fr] Valencien

Le valencien (en catalan : valencià), parfois dénommé catalan méridional, est un dialecte catalan traditionnellement parlé dans la plus grande partie de l'actuelle Communauté valencienne, en Espagne, introduit par les colons de la principauté de Catalogne dans le royaume de Valence nouvellement constitué après la reconquête des territoires musulmans par Jacques Ier d'Aragon dans la première moitié du XIIIe siècle[2].[it] Dialetto valenciano

Il valenzano[1][2] o valenciano[1] (valencià in valenzano) è una varietà normata[3] della lingua catalana parlata in Spagna nella Comunità Valenzana. Dal punto di vista linguistico, è un dialetto[4][2] meridionale[5][6] del catalano (appartenente al gruppo dialettale occidentale[7]), che viene regolato come varietà colta propria della regione in modo da sottolineare le differenze con il catalano normato in Catalogna[8]. Perciò, è denominato anche lingua valenzana (llengua valenciana)[9].[ru] Валенсийский диалект

Валенсийский диалект (кат. valencià), иногда валенсийский язык, валенсийское наречие, — диалект каталанского языка, на котором говорят жители испанского автономного сообщества Валенсия.Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии