lingvo.wikisort.org - Language

Gallo is a regional language of eastern Brittany. It is one of the langues d'oïl, a Romance sub-family that includes French. Today it is spoken only by a minority of the population, as the standard form of French now predominates in this area.

This article may be expanded with text translated from the corresponding article in French. (May 2013) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2008) |

| Gallo | |

|---|---|

| galo | |

| Native to | France |

Native speakers | 191,000 (2012)[1] |

Language family | |

Early forms | |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | France

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | gall1275 |

| ELP | Gallo |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAA-hb |

| IETF | fr-gallo |

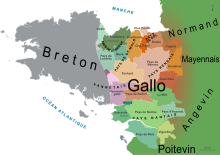

The historical Gallo language area of Upper Brittany | |

Gallo was originally spoken in the Marches of Neustria, an area now corresponding to the border lands between Brittany, Normandy, and Maine. Gallo was a shared spoken language among many of those who took part in the Norman conquest of England, most of whom originated in Upper (i.e. eastern) Brittany and Lower (i.e. western) Normandy, and thus had its part, together with the much bigger role played by the Norman language, in the development of the Anglo-Norman variety of French which would have such a strong influence on English.

Gallo continued as the everyday language of Upper Brittany, Maine, and some neighbouring portions of Normandy until the introduction of universal education across France, but is spoken today by only a small (and aging) minority of the population, having been almost entirely superseded by standard French.

As a langue d'oïl, Gallo forms part of a dialect continuum which includes Norman, Picard, and the Poitevin dialect among others. One of the features that distinguish it from Norman is the absence of Old Norse influence. There is some limited mutual intelligibility with adjacent varieties of the Norman language along the linguistic frontier and with Guernésiais and Jèrriais. However, as the dialect continuum shades towards Mayennais, there is a less clear isogloss. The clearest linguistic border is that distinguishing Gallo from Breton, a Brittonic Celtic language traditionally spoken in the western territory of Brittany.

In the west, the vocabulary of Gallo has been influenced by contact with Breton, but remains overwhelmingly Latinate. The influence of Breton decreases eastwards across Gallo-speaking territory.

As of 1980[update], Gallo's western extent stretches from Plouha (Plóha), in Côtes-d'Armor, south of Paimpol, passing through Châtelaudren (Châtié), Corlay (Corlaè), Loudéac (Loudia), east of Pontivy, Locminé (Lominoec), Vannes, and ending in the south, east of the Rhuys peninsula, in Morbihan.

Nomenclature

While most often spelled Gallo, the name of the language is sometimes written as Galo or Gallot.[2] It is also referred to as langue gallèse or britto-roman in Brittany.[2] In south Lower Normandy and in the west of Pays de la Loire it is often referred to as patois,[3] though this is a matter of some contention.[4] Gallo comes from the Breton word gall, meaning 'foreigner', 'French' or 'non-Breton'.[2][5] The term was first used by Breton speakers, which may explain why it is used rarely by Gallo speakers themselves. Henriette Walter conducted a survey in 1986 which showed that just over 4% of Gallo speakers in Côtes-d'Armor had ever used the term, and a third of them found it "had quite a pejorative connotation". According to the survey, the term patois was the most common way of referring to the language.[6]

The term britto-roman was coined by the linguist Alan-Joseph Raude in 1978 to highlight the fact that Gallo is "a Romance variety spoken by Bretons".[4] Gallo should not be confused with Gallo-Roman, a term that refers to the Romance varieties of ancient Gaul.

Linguistic classification

Gallo is one of the langues d'oïl, a dialect continuum covering the northern half of France. This group includes a wide variety of more or less well-defined and differentiated languages and dialects, which share a Latin origin and some Germanic influence from Frankish, the language spoken by the Franks.[7]

Gallo, like the other langues d'oïl, is neither ancient French nor a distortion of modern French.[8] The langues d'oïl are Gallo-Romance languages, which also includes Franco-provençal, spoken around Savoy. These are in turn Romance languages, a group which also includes, among others, Catalan, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese and Romanian.

Gallo has not just borrowed words from Breton, but also aspects of grammar; the use of the preposition pour as an auxiliary verb is said to be of Celtic origin. The relationship between the two is comparable to that of the two languages of Scotland: Scots, an Anglic language closely related to English, and Scottish Gaelic, a Celtic language descended from Old Irish.[9]

Celtic, Latin and Germanic roots

The Celts settled in Armorica toward the 8th century BCE. Some of early groups mentioned in the written records of the Greeks were the Redones and the Namnetes. They spoke dialects of the Gaulish language[10] and maintained important economic ties with the British Isles.[11] Julius Caesar's invasion of Armorica in 56 BC led to a sort of Romanization of the population.[12] Gaulish continued to be spoken in this region until the 6th century CE,[13] especially in less populated, rural areas. When the Bretons emigrated to Armorica around this time, they found a people who had retained their Celtic language and culture.[14] The Bretons were therefore able to integrate easily.

In contrast to Armorica's eastern countryside, Nantes and Rennes were Roman cultural centres. Following the Migration Period,[11] these two cities, as well as regions to the east of the Vilaine, including the town Vannes,[15] fell under Frankish rule.[11] Thus, during the Merovingian dynasty, the population of Armorica was diverse, consisting of Gaulish tribes with assimilated Bretons, as well as Romanized cities and Germanic tribes.[16] War between the Frank and Breton kingdoms was constant between the 6th and 9th centuries,[11] which made the border between the two difficult to define. Before the 10th century, Breton was spoken by at least one third of the population[17] up to the cities of Pornic and Avranches.

Decline of Gallo

Historically, France has been a nation with a high degree of linguistic diversity matched with relative tolerance, that is until the French Revolution.[18] Gallo's status as a tolerated regional language of France suffered as a direct consequence of the Revolution. During this time, the Jacobins viewed regional languages as a way in which the structural inequalities of France were perpetuated.[18] Accordingly, they sought to eradicate the regional languages to free their speakers of unconstitutional inequalities.

Under the Third Republic, public education became universal and mandatory in France, and was conducted exclusively in French; students who spoke other languages were punished. Well into the 20th century, government policy focused exclusively on French. In 1962, Charles de Gaulle established the Haut Comité pour la défense et l'expansion de la langue française; this committee's purpose was to enforce the use of French, to the detriment of minority languages.[19] Furthermore, in 1994, the Loi Toubon declared that any governmental publications and advertisements must be in French.[19] Like all of the other regional languages of France, the use of Gallo has declined since the 19th century.

Similar to speakers of other regional languages, Gallo speakers began to associate French as the language of intellectuals and social promotion, and Gallo as an impediment to their success.[20] As a result, the rate of children learning the language has diminished, since parents struggle to see the benefit of Gallo in their children's future.

Gallo and education

Within recent history, the presence of Gallo has fluctuated in Brittany's school system. Shortly before World War II, the Regional Federation of Bretagne introduced the idea of rejuvenating Gallo's presences in schools.[21] They were primarily motivated in increasing the linguistic competence of children.[21]

In 1982, Gallo was officially adopted as an optional subject in secondary schools in Brittany, even appearing on France's secondary school-exit exam, the Baccalaureat.[21] It took years for the Gallo language to actually be incorporated into the curriculum, but by the 1990s, the main focus of the curriculum was cultural awareness of the Gallo language and identity.[21] However, in 2002, Gallo's optional-subject status in secondary schools was withdrawn.[21]

In reaction to the 2002 decision, an effective and committed network of Gallo activists advanced Gallo's status in Brittany schools.[22] Gallo is now taught in Upper Brittany's state schools, though the number of students enrolled in Gallo courses remains low. In the 2003-04 academic year, there were 569 students learning Gallo at secondary school or university .[22] For comparison, in the same year, 3,791 students were learning Breton at the same levels of schooling.[22]

Status

One of the metro stations of the Breton capital, Rennes, has bilingual signage in French and Gallo, but generally the Gallo language is not as visibly high-profile as the Breton language, even in its traditional heartland of the Pays Gallo, which includes the two historical capitals of Rennes (Gallo Resnn, Breton Roazhon) and Nantes (Gallo Nauntt, Breton Naoned).

Different dialects of Gallo are distinguished, although there is a movement for standardisation on the model of the dialect of Upper Brittany.

It is difficult to record the exact number of Gallo speakers today. Gallo and vernacular French share a social-linguistic landscape, so speakers have difficulty determining exactly which language they are speaking.[18] This makes estimates of the number of speakers vary widely.[18]

Literature

Although a written literary tradition exists, Gallo is more noted for extemporised story-telling and theatrical presentations. Given Brittany's rich musical heritage, contemporary performers produce a range of music sung in Gallo (see Music of Brittany).

The roots of written Gallo literature are traced back to Le Livre des Manières written in 1178 by Etienne de Fougères, a poetical text of 336 quatrains and the earliest known Romance text from Brittany, and to Le Roman d'Aquin, an anonymous 12th century chanson de geste transcribed in the 15th century but which nevertheless retains features typical of the mediaeval Romance of Brittany. In the 19th century oral literature was collected by researchers and folklorists such as Paul Sébillot, Adolphe Orain, Amand Dagnet and Georges Dottin. Amand Dagnet (1857-1933) also wrote a number of original works in Gallo, including a play La fille de la Brunelas (1901).[23]

It was in the 1970s that a concerted effort to promote Gallo literature started. In 1979 Alan J. Raude published a proposed standardised orthography for Gallo.[24]

Examples

| English | Gallo | Old French | French |

|---|---|---|---|

| afternoon | vêpré | vespree | après-midi (archaic: vêprée) |

| apple tree | pommieu | pomier | pommier |

| bee | avètt | aveille | abeille |

| cider | cit | cidre | cidre |

| chair | chaérr | chaiere | chaise |

| cheese | fórmaij | formage | fromage |

| exit | desort | sortie | sortie |

| to fall | cheir | cheoir | tomber (archaic: choir) |

| goat | biq | chievre, bique | chèvre (slang: bique) |

| him | li | lui, li | lui |

| house | ostèu | hostel | maison (hôtel) |

| kid | garsaille | same root as Old French gars | Same root as gars, garçon |

| lip | lip | levre | lèvre (or lippe) |

| maybe | vantiet | puet estre | peut-être |

| mouth | góll | goule, boche | bouche (gueule = mouth of an animal) |

| now | astour | a ceste heure | maintenant (à cette heure) |

| number | limerot | nombre | numéro |

| pear | peirr | peire | poire |

| school | escoll | escole | école |

| squirrel | chat-de-boéz (lit. "woods cat") | escurueil | écureuil |

| star | esteill | esteile, estoile | étoile |

| timetable | oryaer | horaire | horaire |

| to smoke | betunae | fumer | fumer (archaic: pétuner) |

| today | anoet | hui | aujourd'hui |

| to whistle | sublae | sibler, sifler | siffler |

| with | ô or côteu avek | o/od, avoec | avec |

Films

- Of Pipers and Wrens (1997). Produced and directed by Gei Zantzinger, in collaboration with Dastum. Lois V. Kuter, ethnomusicological consultant. Devault, Pennsylvania: Constant Spring Productions.

References

- "Enquête socio-linguistique : qui parle les langues de Bretagne aujourd'hui ?" [Socio-linguistic survey: who speaks the languages of Brittany today?]. Région Bretagne (in French). 8 October 2018.

- Chevalier, Gwendal (2008), "Gallo et Breton, complémentarité ou concurrence?" [Gallo and Breton, complementarity or competition?], Cahiers de sociolinguistique (in French) (12): 75–109, doi:10.3917/csl.0701.0075, retrieved 2018-10-09

- "Gallo language, alphabet and pronunciation". Omniglot.com. Retrieved 2018-10-09.

- Leray, Christian and Lorand, Ernestine. Dynamique interculturelle et autoformation: une histoire de vie en Pays gallo. L'Harmattan. 1995.

- Walter, Henriette. "Les langues régionales de France : le gallo, pris comme dans un étau (17/20)". www.canalacademie.com. Canal Académie.

- Walker, Henriette (2000). Le français d'ici, de là, de là-bas. Le Livre de Poche. p. 113. ISBN 978-2253149293.

- Abalain, Hervé (2007). Le français et les langues historiques de la France. Jean-Paul Gisserot. p. 57.

- Machonis, Peter A. (1990). Histoire de la langue : Du latin à l'ancien français. University Press of America. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-8191-7874-9.

- DeKeyser, Robert; Walter, Henriette (September 1995). "L'aventure des langues en Occident: Leur origine, leur histoire, leur géographie". Language. 71 (3): 659. doi:10.2307/416271. ISSN 0097-8507. JSTOR 416271.

- Celtic Countries, "Gallo Language" 04 March 2014

- "The Ruin and Conquest of Britain 400 A.D. - 600 A.D" 04 March 2014

- Ancient Worlds Archived 2012-01-06 at the Wayback Machine "Armorica" 04 March 2014

- [permanent dead link] "Gaulish Language" 04 March 2014

- Bretagne.fr "An Overview of the Languages Used in Brittany" 04 March 2014

- Encyclopædia Britannica, "Vannes" 13 April 2014

- [permanent dead link] "France" 04 March 2014

- Sorosoro "Breton" 04 March 2014

- Nolan, John Shaun (2011). "Reassessing Gallo as a regional language in France: language emancipation vs. monolingual language ideology". International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 2011 (209). doi:10.1515/ijsl.2011.023. S2CID 147587111.

- Radford, Gavin (2015-03-04), "French language law: The attempted ruination of France's linguistic diversity", Trinity College Law Review (TCLR) online, retrieved 2016-11-07

- Hervé, Gildas d'. "Le Gallo dans l'enseignement, l'enseignement du gallo" (PDF). Marges linguistiques. Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- Le-Coq, André (2009-09-01). "L'enseignement du gallo". Tréma (in French) (31): 39–45. doi:10.4000/trema.942. ISSN 1167-315X.

- Nolan, John Shaun (2008). "The Role of Gallo in the Identity of Upper-Breton School Pupils of the Language Variety and their Parents". Sociolinguistic Studies. 2 (1). doi:10.1558/sols.v2i1.131. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- Bourel, Claude (2001). Contes et récits du Pays Gallo du XIIe siècle à nos jours. Fréhel: Astoure. ISBN 2845830262.

- Paroles d'oïl. Mougon: Geste. 1994. ISBN 2905061952.

На других языках

- [en] Gallo language

[es] Idioma galó

El galó (o brito-románico) es una de las lenguas propias de Bretaña, junto con el bretón. Es una lengua románica, más concretamente una lengua d'oïl. Es similar al normando pero con más influencias celtas, debido a su vecindad con el bretón. Hoy en día se encuentra en franca regresión ante el francés, ya que, a diferencia del valón, tiene muy poca literatura escrita, a pesar de que fue la lengua de la corte de los duques de Bretaña hasta su incorporación a Francia. Se conoce poco sobre ella, ya que se ha estudiado muy poco, excepto el estudio de Paul Sébillot, y tampoco es usada en los medios de comunicación, aunque últimamente ha habido ciertos intentos de hacerla revivir, por ejemplo a través de las asociaciones Bertaèyn Galeizz y Maézoe.[fr] Gallo

Le gallo (endonyme galo[2]) ou la langue gallèse est l'une des langues d'oïl de la Haute-Bretagne. Il est traditionnellement parlé en Ille-et-Vilaine, dans la Loire-Atlantique et dans l'est du Morbihan et des Côtes-d'Armor, derrière une frontière linguistique allant de Plouha à Guérande. La limite orientale du gallo est moins claire, car il existe un continuum avec les langues d'oïl voisines (mainiau mayennais, normand, angevin...). Certains linguistes considèrent par exemple que le gallo s'étend dans des régions contiguës à la Bretagne historique, en particulier dans l'aire plus vaste du Massif armoricain.[it] Gallo (lingua)

Il gallo (nome nativo galo, in francese gallo, pronuncia sempre /ɡa.lo/) è una lingua romanza, diffusa nella regione francese della Bretagna, insieme al bretone, che appartiene invece al ramo celtico delle lingue indoeuropee. Viene definito anche langue gallèse (termine francese da non confondere con gallois, "gallese"), britto-romanzo, alto-bretone.[ru] Галло (язык)

Галло (фр. Le gallo) — традиционный романский идиом/язык/диалект, развившийся из народно-латинского языка на полуострове Бретань (Галлия). В современной Франции сохраняется преимущественно как язык регионального фольклора, хотя с 1982 г. ведётся его факультативное преподавание, в последнее время в Бретани появилось также много двуязычных и даже триязычных надписей (французский, бретонский и галло). Распадается на несколько поддиалектов и переходных говоров.Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии