lingvo.wikisort.org - Language

Maithili (English: /ˈmaɪtɪli/[5]) is an Indo-Aryan language spoken in parts of India and Nepal. It is native to the Mithila region, which encompasses parts of the Indian states of Bihar and Jharkhand as well as Nepal's eastern Terai. It is one of the 22 officially recognised languages of India[6][1][2] and the second most spoken Nepalese language in Nepal.[7][8]

| Maithili | |

|---|---|

| मैथिली | |

| Native to | India and Nepal |

| Region | Mithila[lower-alpha 1] |

| Ethnicity | Maithil |

Native speakers | 34 million (2000)[3] |

Language family | Indo-European

|

Writing system | Devanagari and others |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | mai |

| ISO 639-3 | mai |

| Glottolog | mait1250 |

Maithili-speaking region of India and Nepal | |

| Part of a series on | |

|---|---|

| |

| Constitutionally recognised languages of India | |

| Category | |

| 22 Official Languages of the Indian Republic | |

|

Assamese

·

Bengali

·

Bodo

·

Dogri

·

Gujarati

| |

| Related | |

|

Eighth Schedule to the Constitution of India

| |

|

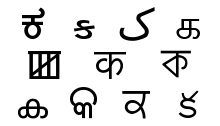

The language is predominantly written in Devanagari, but there were two other historically important scripts: Tirhuta, which has retained some use until the present, and Kaithi.

Official status

In 2003, Maithili was included in the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution as a recognised Indian language, which allows it to be used in education, government, and other official contexts in India.[6] Maithili language is included as an optional paper in the UPSC Exam. In March 2018, Maithili received the second official language status in the Indian state of Jharkhand.[9]

The Language Commission of Nepal has recommended Maithili language to be made an official administrative language in Province No. 1 and Province No. 2.[10]

Geographic distribution

In India, Maithili is spoken mainly in Bihar and Jharkhand in the districts of Darbhanga, Saharsa, Samastipur, Madhubani, Muzaffarpur, Sitamarhi, Begusarai, Munger, Khagaria, Purnia, Katihar, Kishanganj, Sheohar, Bhagalpur, Madhepura, Araria, Supaul, Vaishali and Deoghar as well as other districts of Santhal Pargana division.[11][12] Darbhanga, Madhubani and Saharsa constitute cultural and linguistic centers.[13]

In Nepal, Maithili is spoken mainly in the Outer Terai districts including Sarlahi, Mahottari, Dhanusa, Sunsari, Siraha, Morang and Saptari Districts. Janakpur is an important linguistic centre of Maithili.[13]

Classification

In the 19th century, linguistic scholars considered Maithili as a dialect of Bihari languages and grouped it with other languages spoken in Bihar. Hoernlé compared it with the Gaudian languages and recognised that it shows more similarities with the Bengali languages than with Hindi. Grierson recognised it as a distinct language and published its first grammar in 1881.[14][15]

Chatterji grouped Maithili with the Magadhi Prakrit.[16]

Dialects

Some of this section's listed sources may not be reliable. (October 2022) |

Maithili varies greatly in dialects.[17] The standard form of Maithili is Central Maithili[18] which is mainly spoken in Darbhanga, Begusarai district , Madhubani district and Saharsa district in Bihar, India.[19]

- Bajjika (Western Maithili) is spoken in Sitamarhi, Muzaffarpur, Vaishali, East Champaran, Sheohar and Eastern part of Saran[20][21] of Bihar in India. Western Maithili is listed as a distinct language in Nepal and overlaps by 76–86% with Maithili dialects spoken in Dhanusa, Morang, Saptari, and Sarlahi Districts.[22]

- Thēthi Maithili is spoken mainly in Kosi, Purnia and Munger divisions and Patna's Mokama in Bihar, India and some adjoining districts of Nepal.[23]

- Angika (Chhika Chhiki Maithili) is spoken in and around the Bhagalpur, Banka,[24] Jamui, Munger[25] and Santhal Pargana division.[26][27]

- Eastern Maithili mainly spoken in Kishanganj, Araria, Purnia also some part of Katihar.[28]

- Southern Maithili widely spoken in Deoghar also called Deogharia Maithili.[29]

- Several other dialects of Maithili are spoken in India and Nepal, including Dehati, Deshi, Kisan, Bantar, Barmeli, Musar, Tati and Jolaha. All the dialects are intelligible to native Maithili speakers.[13]

Origin and history

The name Maithili is derived from the word Mithila, an ancient kingdom of which King Janaka was the ruler (see Ramayana). Maithili is also one of the names of Sita, the wife of King Rama and daughter of King Janaka. Scholars in Mithila used Sanskrit for their literary work and Maithili was the language of the common folk (Abahatta).

The beginning of Maithili language and literature can be traced back to the 'Charyapadas', a form of Buddhist mystical verses, composed during the period of 700-1300 AD. These padas were written in Sandhya bhasa by several Siddhas who belonged to Vajrayana Buddhism and were scattered throughout the territory of Assam, Bengal, Bihar and Odisha. Several of Siddas were from Mithila region such as Kanhapa, Sarhapa etc. Prominent scholars like Rahul Sankrityanan, Subhadra Jha and Jayakant Mishra provided evidence and proved that the language of Charyapada is ancient Maithili or proto Maithili.[30] Apart from Charyapadas, there has been rich tradition of folk culture, folk songs and which were popular among common folks of Mithila region.[31]

After the fall of Pala rule, disappearance of Buddhism, establishment of Karnāta kings and patronage of Maithili under Harisimhadeva (1226–1324) of Karnāta dynasty dates back to the 14th century (around 1327 AD). Jyotirishwar Thakur (1280–1340) wrote a unique work Varnaratnākara in Maithili prose.[32] The Varna Ratnākara is the earliest known prose text, written by Jyotirishwar Thakur in Mithilaksar script,[14] and is the first prose work not only in Maithili but in any modern Indian language.[33]

In 1324, Ghyasuddin Tughluq, the emperor of Delhi invaded Mithila, defeated Harisimhadeva, entrusted Mithila to his family priest and a great Military Scholar Kameshvar Jha, a Maithil Brahmin of the Oinwar dynasty. But the disturbed era did not produce any literature in Maithili until Vidyapati Thakur (1360 to 1450), who was an epoch-making poet under the patronage of king Shiva Singh and his queen Lakhima Devi. He produced over 1,000 immortal songs in Maithili on the theme of love of Radha and Krishna and the domestic life of Shiva and Parvati as well as on the subject of suffering of migrant labourers of Morang and their families; besides, he wrote a number of treaties in Sanskrit. His love-songs spread far and wide in no time and enchanted saints, poets and youth. Chaitanya Mahaprabhu saw the divine light of love behind these songs, and soon these songs became themes of Vaisnava sect of Bengal. Rabindranath Tagore, out of curiosity, imitated these songs under the pseudonym Bhanusimha. Vidyapati influenced the religious literature of Asama, Bengal, Utkala and gave birth to a new Brajabuli language.[34][35]

The earliest reference to Maithili or Tirhutiya is in Amaduzzi's preface to Beligatti's Alphabetum Brammhanicum, published in 1771.[36] This contains a list of Indian languages amongst which is 'Tourutiana.' Colebrooke's essay on the Sanskrit and Prakrit languages, written in 1801, was the first to describe Maithili as a distinct dialect.[37]

Many devotional songs were written by Vaisnava saints, including in the mid-17th century, Vidyapati and Govindadas. Mapati Upadhyaya wrote a drama titled Pārijātaharaṇa in Maithili. Professional troupes, mostly from dalit classes known as Kirtanias, the singers of bhajan or devotional songs, started to perform this drama in public gatherings and the courts of the nobles. Lochana (c. 1575 – c. 1660) wrote Rāgatarangni, a significant treatise on the science of music, describing the rāgas, tālas, and lyrics prevalent in Mithila.[38]

During the Malla dynasty's rule Maithili spread far and wide throughout Nepal from the 16th to the 17th century.[39][40] During this period, at least seventy Maithili dramas were produced. In the drama Harishchandranrityam by Siddhinarayanadeva (1620–57), some characters speak pure colloquial Maithili, while others speak Bengali, Sanskrit or Prakrit.[41]

After the demise of Maheshwar Singh, the ruler of Darbhanga Raj, in 1860, the Raj was taken over by the British Government as regent. The Darbhanga Raj returned to his successor, Maharaj Lakshmishvar Singh, in 1898. The Zamindari Raj had a lackadaisical approach toward Maithili. The use of Maithili language was revived through personal efforts of MM Parameshvar Mishra, Chanda Jha, Munshi Raghunandan Das and others.[42][43]

Publication of Maithil Hita Sadhana (1905), Mithila Moda (1906), and Mithila Mihir (1908) further encouraged writers. The first social organisation, Maithil Mahasabha,[44] was established in 1910 for the development of Mithila and Maithili. It blocked its membership for people outside of the Maithil Brahmin and Karna Kayastha castes. Maithil Mahasabha campaigned for the official recognition of Maithili as a regional language. Calcutta University recognised Maithili in 1917, and other universities followed suit.[45]

Babu Bhola Lal Das wrote Maithili Grammar (Maithili Vyakaran). He edited a book Gadya Kusumanjali and edited a journal Maithili.[46] In 1965, Maithili was officially accepted by Sahitya Academy, an organisation dedicated to the promotion of Indian literature.[47][48]

In 2002, Maithili was recognised on the VIII schedule of the Indian Constitution as a major Indian language; Maithili is now one of the twenty-two Scheduled languages of India.[49]

The publishing of Maithili books in Mithilakshar script was started by Acharya Ramlochan Saran.[50][51]

Phonology

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| Close | ɪ ⟨इ⟩ | iː ⟨ई⟩ | ʊ ⟨उ⟩ | uː ⟨ऊ⟩ | ||

| Mid | e ⟨ऎ⟩ | eː ⟨ए⟩ | ə~ɐ ⟨अ⟩ | əː ⟨अऽ⟩ | o ⟨ऒ⟩ | oː ⟨ओ⟩ |

| Open | æ~ɛ ⟨ऍ⟩ | a ⟨ॴ⟩ | aː ⟨आ⟩ | ɔ ⟨अऽ⟩ | ||

| Diphthongs | əe̯ ⟨ꣾ⟩ | əo̯ ⟨ॵ⟩ | ||||

| aːɪ̯ ⟨ऐ⟩ | aːʊ̯ ⟨औ⟩ | |||||

- All vowels have nasal counterparts, represented by "~" in IPA and ँ on the vowels, like आँ ãː .

- All vowel sounds are realised as nasal when occurring before or after a nasal consonant.[52]

- Sounds eː and oː are often replaced by diphthongs əɪ̯ and əʊ̯.[citation needed]

- æ is a recent development.

- ɔ is replaced by ə in northern dialects and by o in southernmost dialects.

- There are three short vowels, as described by Grierson, but not counted by modern grammarians. But they could be understood as syllable break :- ॳ / ɘ̆ /, इऺ/ ɪ̆ /, उऺ/ ʊ̆ / . Or as syllable break ऺ in Devanagari and "." in IPA.

- ꣾ is a Unicode letter in Devanagari, (IPA /əe̯/) which is not supported currently on several browsers and operating systems, along with its mātrā (vowel sign).

The following diphthongs are present:[citation needed]

- अय़(ꣾ) / əi̯ / ~ /ɛː/ - अय़सनऺ (ꣾ सनऺ) / əi̯sənᵊ / ~ /ɛːsɐnᵊ/ 'like this'

- अव़(ॵ) / əu̯ / ~ /ɔː/- चव़मुुखऺ(चॏमुखऺ) / tɕəu̯mʊkʰᵊ / ~ /tɕɔːmʊkʰᵊ/ 'four faced'

- अयॆ / əe̯ / - अयॆलाः / əe̯la:h / 'came'

- अवॊ (अऒ) / əo̯ / - अवॊताः / əo̯ta:h / 'will come'

- ऐ / a:i̯ / - ऐ / a:i̯ / 'today'

- औ / a:u̯ / - औ / a:u̯ / 'come please'

- आयॆ (आऎ) / a:e̯ / - आयॆलऺ / a:e̯l / 'came'

- आवॊ (आऒ) / a:o̯ / - आवॊबऺ / a:o̯bᵊ / 'will come'

- यु (इउ) / iu̯/ - घ्यु / ghiu̯ / 'ghee'

- यॆ (इऎ) / ie̯ / - यॆः / ie̯h / 'only this'

- यॊ (इऒ) / io̯ / - कह्यो / kəhio̯ / 'any day'

- वि (उइ) / ui̯ / - द्वि / dui̯ / 'two'

- वॆ (उऎ) /ue̯/ - वॆ: / ue̯h / 'only that'

A peculiar type of phonetic change is recently taking place in Maithili by way of epenthesis, i.e. backward transposition of final i and u in all sort of words.[53] Thus:

Standard Colloquial - Common Pronunciation

- अछि / əchi / - अइछऺ / əich / 'is'

- रवि / rəbi / - रइबऺ / rəib / 'Sunday'

- मधु / mədhu / - मउधऺ / məudh / 'honey'

- बालु / ba:lu / - बाउलऺ / ba:ul / 'sand'

Consonants

Maithili has four classes of stops, one class of affricate, which is generally treated as a stop series, related nasals, fricatives and approximant.

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m ⟨म⟩ | n ⟨न⟩ | ɳ ⟨ण⟩ | (ɲ) ⟨ञ⟩ | ŋ ⟨ङ⟩ | |||

| Plosive/ Affricate |

voiceless | unaspirated | p ⟨प⟩ | t ⟨त⟩ | ʈ ⟨ट⟩ | tɕ ⟨च⟩ | k ⟨क⟩ | |

| aspirated | pʰ ⟨फ⟩ | tʰ ⟨थ⟩ | ʈʰ ⟨ठ⟩ | tɕʰ ⟨छ⟩ | kʰ ⟨ख⟩ | |||

| voiced | unaspirated | b ⟨ब⟩ | d ⟨द⟩ | ɖ ⟨ड⟩ | dʑ ⟨ज⟩ | ɡ ⟨ग⟩ | ||

| aspirated | bʱ ⟨भ⟩ | dʱ ⟨ध⟩ | ɖʱ ⟨ढ⟩ | dʑʱ ⟨झ⟩ | ɡʱ ⟨घ⟩ | |||

| Fricative | voiceless | (ɸ~f) ⟨फ़⟩ | s ⟨स⟩ | (ʂ) ⟨ष⟩ | (ɕ) ⟨श⟩ | (x) ⟨ख़⟩ | -(h)* ⟨ः⟩ | |

| voiced | (z) ⟨ज़⟩ | (ʑ) ⟨झ़⟩ | (ɦ) ⟨ह⟩ | |||||

| Rhotic | unaspirated | ɾ~r ⟨र⟩ | (ɽ) ⟨ड़⟩ | |||||

| aspirated | (ɽʱ) ⟨ढ़⟩ | |||||||

| Lateral | l ⟨ल⟩ | |||||||

| Approximant | (ʋ~w) ⟨व⟩ | (j) ⟨य⟩ | ||||||

Stops

There are four series of stops- bilabials, coronals, retroflex and velar, along with an affricate series. All of them show the four way contrast like most of the modern Indo-Aryan languages:

- tenuis, as /p/, which is like ⟨p⟩ in English spin

- voiced, as /b/, which is like ⟨b⟩ in English bin

- aspirated, as /pʰ/, which is like ⟨p⟩ in English pin, and

- murmured or aspirated voiced, as /bʱ/.

Apart from the retroflex series, all the rest four series show full phonological contrast in all positions. The retroflex tenius ʈ and ʈʰ show full contrast in all positions. ɖ and ɖʱ show phonological contrast mainly word-initially.[54] Both are defective phonemes, occurring intervocalically an word finally only if preceded by a nasal consonant. Word finally and postvocalically, ɖʱ surfaces as ɽʱ or rʱ.[55] Non-initially, both are interchangeable with ɽ or r and ɽʱ or rʱ respectively.[54]

Fricatives

s and h are most common fricatives. They show full phonological opposition. ɕ and ʂ, which is present in tatsama words, is replaced by s most of the times, when independent. ɕ occurs before tɕ and ʂ before ʈ. x and f occurs in Perso-Arabic loanwords, generally replaced by kʰ and pʰ respectively. x and ɸ also occurs in Sanskrit words (jihvamuliya and upadhmaniya), which is peculiar to Maithili.

- Fricative sounds [ʂ, ɕ] only occur marginally, and are typically pronounced as a dental fricative /s/ in most styles of pronunciation.ः is always added after a vowel.

Sonorants

m and n are present in all phonological positions. ŋ occurs only non-initially and is followed by a homorganic stop, which may be deleted if voiced, which leads to the independent presence of ŋ. ɳ occurs non-initially, followed by a homorganic stop, and is independent only in tatsama words, which is often replaced with n. ɲ occurs only non-initially and is followed by a homorganic stop always. It is the only nasal which does not occur independently.

- In most styles of pronunciation, the retroflex flap [ɽ] occurs marginally, and is usually pronounced as an alveolar tap /r/ sound.

- Approximant sounds [ʋ, w, j] and fricative sounds [ɸ, f, z, ʑ, x], mainly occur in words that are borrowed from Sanskrit or in words of Perso-Arabic origin. From Sanskrit, puʂp(ə) as puɸp(ə). Conjunct of ɦj as ɦʑ as in graɦjə as graɦʑə.[54]

There are four non-syllabic vowels in Maithili- i̯, u̯, e̯, o̯ written in Devanagari as य़, व़, य़ॆ, व़ॊ. Most of the times, these are written without nukta.

Morphology

Nouns

An example declension:

| Case name | Singular Inflection | Plural Inflection | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feminine | Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | Masculine | Neuter | |

| Nominative | -इ ɪ | -आ/अऽ aː/ɔ | -इन ɪnᵊ | -अन, -अनि

ənᵊ, ənɪ̆ |

-अन, -अनि

ənᵊ, ənɪ̆ | |

| Accusative

(Indefinite) |

-ई iː | -ई iː | -आ aː | |||

| Instrumental | Postposition used |

-एँ ẽː | Postposition used | -अन्हि

ənʰɪ̆ | ||

| Dative | Postposition used | |||||

| -इल ɪlə | -अल ələ | No forms | ||||

| Ergative | -इएँ ɪẽː | -एँ ẽː | ||||

| Ablative | -इतः ɪtəh | -अतः

ətəh | ||||

| Genitive | -इक ɪkᵊ, इर ɪrᵊ | -अक əkᵊ, -अर ərᵊ | -ईंक ĩːkᵊ | -आँँक

ãːkᵊ | ||

| Locative | Postposition used | -ए eː | Postposition used | -आँ

ãː | ||

| Vocative | -इ ɪ/ई iː | -आ/अऽ aː/əː | -इन ɪnᵊ | -अन, -अनि

ənᵊ, ənɪ̆ | ||

Adjectives

The difference between adjectives and nouns is very minute in Maithili. However, there are marked adjectives there in Maithili.

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definite | -का/कऽ kaː/kɔ | -कि/कि kɪ/kɪ̆ | का/कऽ kaː/kəː |

| Indefinite | -आ/अऽ aː/ɔ | -इ/इ ɪ/ɪ̆ | अ/अऽ ᵊ/əː |

Pronouns

Pronouns in Maithili are declined in similar way to nominals, though in most pronouns the genitive case has a different form. The lower forms below are accusative and postpositional. The plurals are formed periphrastically.

| Person | First Grade Honour | Honorofic | High Honorofic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Person | हम ɦəmᵊ

अपना ɐpᵊnaː (Inclusive) | |||

| हमरा ɦəmᵊraː

अपना ɐpᵊnaː (Inclusive) | ||||

| Second Person | तोँह tõːɦᵊ | अहाँ ɐɦãː | अपने ɐpᵊneː | |

| तोँहरा tõːɦᵊraː | ||||

| Third Person | Proximate | ई iː | ए eː | |

| ऎकरा ekᵊraː | हिनका ɦɪnᵊkaː | |||

| ए eː (Neuter) | ||||

| ऎहि, ऍ, अथि eɦɪ, æ, ɐtʰɪ (Neuter) | ||||

| Non-Proximate | ऊ, वा uː, ʋaː | ओ oː | ||

| ऒकरा okᵊraː | हुनका ɦʊnᵊkaː | |||

| ऒ o (Neuter) | ||||

| ऒहि, ॵ oɦɪ, əʊ (Neuter) | ||||

Writing system

Beginning in the 14th century, the language was written in the Tirhuta script (also known as Mithilakshara or Maithili), which is related to the Bengali script.[56] By the early 20th century, this script was largely associated with the Mithila Brahmans, with most others using Kaithi, and Devanagari spreading under the influence of the scholars at Banaras.[57] Throughout the course of the century, Devanagari grew in use eventually replacing the other two, and has since remained the dominant script for Maithili.[58][56][57] Tirhuta retained some specific uses (on signage in north Bihar as well as in religious texts, genealogical records and letters), and has seen a resurgence of interest in the 21st century.[56]

The Tirhuta and Kaithi scripts are both currently included in Unicode.

Literature

Sample Text

The following sample text is Maithili translation of Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights:

Maithili in the Devanagari alphabet

- अनुच्छेद १:सभ मानव जन्मतः स्वतन्त्र अछि तथा गरिमा आ अधिकारमे समान अछि। सभकेँ अपन–अपन बुद्धि आ विवेक छैक आओर सभकेँ एक दोसरक प्रति सौहार्दपूर्ण व्यवहार करबाक चाही।

Maithili in IAST

- Anuccheda Eka: Sabha mānaba janmataha svatantra achi tathā garimā ā adhikārme samāna achi. Sabhkẽ apana-apana buddhi ā bibeka chaika āora sabhkẽ eka dosarāka prati sauhardapurna byabahāra karabāka cāhī.

Translation

- Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They possess conscience and reason. Therefore, everyone should act in a spirit of brotherhood towards each other.

See also

- Languages with official status in India

- List of Indian languages by total speakers

Notes

- Eastern Bihar and northeastern Jharkhand in India;[1][2] Province No. 2 and Province No. 1 in Nepal)

- It is one of 22 Eighth Schedule languages

Citations

- "मैथिली लिपि को बढ़ावा देने के लिए विशेषज्ञों की जल्द ही बैठक बुला सकते हैं प्रकाश जावड़ेकर". NDTV. 21 March 2018. Archived from the original on 21 March 2018. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- "मैथिली को भी मिलेगा दूसरी राजभाषा का दर्जा". Hindustan. 6 March 2018. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- Maithili at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018)

- "झारखंड : रघुवर सरकार कैबिनेट से मगही, भोजपुरी, मैथिली व अंगिका को द्वितीय भाषा का दर्जा". Archived from the original on 21 March 2018. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- "Maithili". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Nepal". Ethnologue. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- Sah, K. K. (2013). "Some perspectives on Maithili". Nepalese Linguistics (28): 179–188.

- "झारखंड : रघुवर कैबिनेट से मगही, भोजपुरी, मैथिली व अंगिका को द्वितीय भाषा का दर्जा". Prabhat Khabar (in Hindi). 21 March 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- "सरकारी कामकाजको भाषाका आधारहरूको निर्धारण तथा भाषासम्बन्धी सिफारिसहरू (पञ्चवर्षीय प्रतिवेदन- साराांश) २०७८" (PDF). Language Commission. Language Commission. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- "बिहार में मैथिली भाषा आजकल सुर्खियों में क्यों है? त्रेता युग से अब तक मैथिली का सफर".

- "मैथिली को भी मिलेगा दूसरी राजभाषा का दर्जा". Hindustan (in Hindi). 6 March 2018. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- Lewis, M. P., ed. (2009). "Maithili". Ethnologue: Languages of the World (Sixteenth ed.). Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Archived from the original on 22 September 2013. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- Yadav, R. (1979). "Maithili language and Linguistics: Some Background Notes" (PDF). Maithili Phonetics and Phonology. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Kansas, Lawrence. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- Yadav, R. (1996). A Reference Grammar of Maithili. Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin, New York.

- Chatterji, S. K. (1926). The origin and development of the Bengali language. University Press, Calcutta.

- Brass, P. R. (2005). Language, Religion, and Politics in North India. iUniverse, Lincoln, NE.

- Yadav, R. (1992). "The Use of the Mother Tongue in Primary Education: The Nepalese Context" (PDF). Contributions to Nepalese Studies. 19 (2): 178–190. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- Choudhary, P.K. 2013. Causes and Effects of Super-stratum Language Influence, with Reference to Maithili. Journal of Indo-European Studies 41(3/4): 378–391.

- Abhishek Kashyap 2014, p. 1.

- Abhishek Kashyap 2014, pp. 1–2.

- Simons, G. F.; Fennig, C. D., eds. (2018). "Maithili. Ethnologue: Languages of the World". Dallas: SIL International. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- Ray, K. K. (2009). Reduplication in Thenthi Dialect of Maithili Language. Nepalese Linguistics 24: 285–290.

- 2011 Census of India, Population By Mother Tongue

- "language | Munger District, Government of Bihar | India". munger.nic.in. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- "LSI Vol-5 part-2". dsal. p. 95.

Chhika-Chhiki

- "LSI Vol-5 part-2". dsal. p. 13.

- "Eastern Maithili Dialect "www.mustgo.com". Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- "Southern Maithili Dialect "www.mustgo.com". Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- Mishra, J. (1949). A History Of Maithili Literature. Vol. 1.

- "Madhubani Paintings: People's Living Cultural Heritage". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- Chatterji, S. K. (1940). Varna Ratnakara Of Jyotirisvara Kavisekharacarya.

- Reading Asia : new research in Asian studies. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon. 2001. ISBN 0700713719. OCLC 48560711.

- Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra; Pusalker, A. D.; Majumdar, A. K., eds. (1960). The History and Culture of the Indian People. Vol. VI: The Delhi Sultanate. Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. p. 515.

During the sixteenth century, a form of an artificial literary language became established ... It was the Brajabulī dialect ... Brajabulī is practically the Maithilī speech as current in Mithilā, modified in its forms to look like Bengali.

- Morshed, Abul Kalam Manjoor (2012). "Brajabuli". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Ded. St. Borgiae Clementi, XIV. Praef. J. Chr. Amadutii (1771). Alphabetum Brammhanicum Seu Indostanum Universitatis Kasi (in Latin). Palala Press. pp. viii. ISBN 9781173019655.

- Thomas Colebrooke, H. (1873). Miscellaneous essays. With life of the author by his son Sir T.E. Colebrooke, Volume 3. p. 26. ISBN 9781145371071.

- Mishra, Amar Kant (23 November 2018). Ruling Dynasty Of Mithila: Dr.Sir Kameswar Singh. Notion Press. ISBN 978-1-64429-762-9.

- Ayyappappanikkar; Akademi, Sahitya (January 1999). Medieval Indian literature: an anthology, Volume 3. p. 69. ISBN 9788126007882. Archived from the original on 19 February 2017. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- Gellner, D.; Pfaff-Czarnecka, J.; Whelpton, J. (6 December 2012). Nationalism and Ethnicity in a Hindu Kingdom: The Politics and Culture of ... p. 243. ISBN 9781136649561. Archived from the original on 19 February 2017. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- Rahmat Jahan, 1960- (2004). Comparative literature : a case of Shaw and Bharatendu (1st ed.). New Delhi: Sarup & Sons. p. 121. ISBN 81-7625-487-8. OCLC 58526278.

- Jha, Pankaj Kumar (1996). "Language and Nation : The Case of Maithili and Mithila in the First Half of Twentieth Century". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 57: 581–590. JSTOR 44133363. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- Tripathi, Shailaja (14 October 2010). "Moments for masses". The Hindu. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- Vijay Deo Jha, Mithila Research Society (9 March 2019). Maithil Mahasabha Ka Sankshipt Itihas ( Brief History Of Maithili Mahasabha) Pandit Chandranath Mishra Amar.

- Mishra, Jayakanta (1977). "Social Ideals and Patriotism in Maithili Literature (1900-1930)". Indian Literature. 20 (3): 96–101. ISSN 0019-5804. JSTOR 24157493.

- Chatterjee, Ramananda (1964). The Modern Review. Prabasi Press Private, Limited. p. 215.

- Jha, Ramanath (1969). "The Problem of Maithili". Indian Literature. 12 (4): 5–10. ISSN 0019-5804. JSTOR 24157120.

- "Parliament of India". parliamentofindia.nic.in. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- Singh, P. & Singh, A. N. (2011). Finding Mithila between India's Centre and Periphery. Journal of Indian Law & Society 2: 147–181.

- Horst, Kristen Nehemiah (12 October 2011). Acharya Ramlochan Saran. Dign Press. ISBN 978-613-7-39524-0.

- @biharfoundation (11 February 2020). "Acharya Ramlochan Saran, born on 11 February 1889, in #Muzaffarpur district of Bihar, was a Hindi littérateur, grammarian and publisher" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- Yadav, Ramawatar (1996). A Reference Grammar of Maithili. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 15–27.

- "Maithili". lisindia.ciil.org. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- Grierson, George Abraham (1909). An introduction to the Maithili dialect of the Bihari language as spoken in North Bihar (2 ed.). Calcutta: Asiatic Society of Bengal.

- Yadav, Ramawatar (1996). A Reference Grammar of Maithili. Trends in Linguistics: Documentation, 11.: Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 15–27.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Pandey, Anshuman (2009). Towards an Encoding for the Maithili Script in ISO/IEC 10646 (PDF) (Report). p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 May 2011..

- Brass, P. R. (2005) [1974]. Language, Religion and Politics in North India. Lincoln: iUniverse. p. 67. ISBN 0-595-34394-5. Archived from the original on 11 May 2018. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- Yadava, Y. P. (2013). Linguistic context and language endangerment in Nepal. Nepalese Linguistics 28 Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine: 262–274.

External links

- UCLA Language Materials Project : Maithili

- National Translation Mission's (NTM) Maithili Pages

- Videha Ist Maithili ISSN 2229-547X

- Maithili Books

На других языках

[de] Maithili

Maithili (.mw-parser-output .Deva{font-size:120%}@media all and (min-width:800px){.mw-parser-output .Deva{font-size:calc(120% - ((100vw - 800px)/80))}}@media all and (min-width:1000px){.mw-parser-output .Deva{font-size:100%}}मैथिली, maithilī) ist eine indoarische Sprache und gehört zum indoiranischen Zweig der indogermanischen Sprachfamilie. Es wird außerdem zur Gruppe der Bihari-Sprachen gezählt, mit deren anderen Mitgliedern es eng verwandt ist.- [en] Maithili language

[es] Idioma maithili

El maithili (मैथिली maithilī) o maijilí[cita requerida] es una de la familia de lenguas indo-arias las cuales son parte de la gran familia indoeuropea. Lo hablan en el estado indio de Bihar y en el este de la región Terai de Nepal un total de 24 millones de personas. Los lingüistas consideran que el maithili es un idioma índico oriental y por tanto diferente al hindi o indostánico cual el índico central.[fr] Maïthili

Le maïthili (autonyme : मैथिली maithilī) est une langue de la famille des langues indo-iraniennes qui fait partie des langues indo-européennes. Il est parlé en Inde dans l'État du Bihar, et au Népal dans la partie orientale du Teraï. Les linguistes considèrent que le maïthili est une langue indo-aryenne orientale, différente du hindi, alors qu'il a été longtemps considéré comme un dialecte de l'hindi ou du bengalî. Ce n'est qu'en 2003 qu'il a acquis le statut de langue autonome en Inde et depuis 2007 qu'il est reconnu au Népal par la constitution comme l'une des 129 langues népalaises.[it] Lingua maithili

La lingua maithili (मैथिली maithili) è una lingua bihari parlata in India e in Nepal.[ru] Майтхили

Майтхили (самоназвание: मैथिली maithilī) — индоарийский язык, входящий в индоевропейскую семью языков. Распространён в индийском штате Бихар и в Непале.Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии